In the 1970s, the robust mathematical framework of the Standard Model (SM) replaced data observation as the dominant starting point for scientific inquiry in particle physics. Decades-long physics programmes were put together based on its predictions. Physicists built complex and highly successful experiments at particle colliders, culminating in the discovery of the Higgs boson at the LHC in 2012.

Along this journey, particle physicists adapted their methods to deal with ever growing data volumes and rates. To handle the large amount of data generated in collisions, they had to optimise real-time selection algorithms, or triggers. The field became an early adopter of artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, especially those falling under the umbrella of “supervised” machine learning. Verifying the SM’s predictions or exposing its shortcomings became the main goal of particle physics. But with the SM now apparently complete, and supervised studies incrementally excluding favoured models of new physics, “unsupervised” learning has the potential to lead the field into the uncharted waters beyond the SM.

Blind faith

To maximise discovery potential while minimising the risk of false discovery claims, physicists design rigorous data-analysis protocols to minimise the risk of human bias. Data analysis at the LHC is blind: physicists prevent themselves from combing through data in search of surprises. Simulations and “control regions” adjacent to the data of interest are instead used to design a measurement. When the solidity of the procedure is demonstrated, an internal review process gives the analysts the green light to look at the result on the real data and produce the experimental result.

A blind analysis is by necessity a supervised approach. The hypothesis being tested is specified upfront and tested against the null hypothesis – for example, the existence of the Higgs boson in a particular mass range versus its absence. Once spelled out, the hypothesis determines other aspects of the experimental process: how to select the data, how to separate signals from background and how to interpret the result. The analysis is supervised in the sense that humans identify what the possible signals and backgrounds are, and label examples of both for the algorithm.

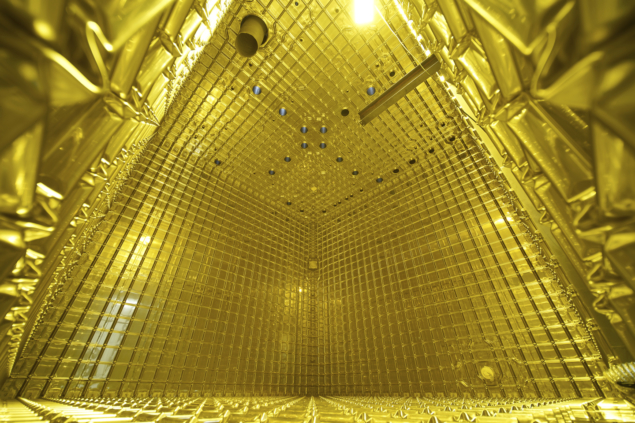

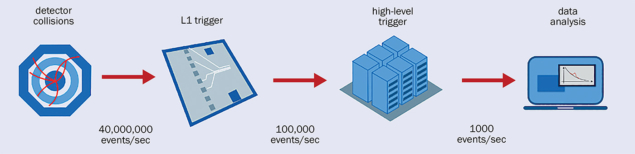

The data flow at the LHC makes the need to specify a signal hypothesis upfront even more compelling. The LHC produces 40 million collision events every second. Each overlaps with 34 others from the same bunch crossing, on average, like many pictures superimposed on top of each other. However, the computing infrastructure of a typical experiment is designed to sustain a data flow of just 1000 events per second. To avoid being overwhelmed by the data pressure, it’s necessary to select these 1000 out of every 40 million events in a short time. But how do you decide what’s interesting?

This is where the supervised nature of data analysis at the LHC comes into play. A set of selection rules – the trigger algorithms – are designed so that the kind of collisions predicted by the signal hypotheses being studied are present among the 1000 (see “Big data” figure). As long as you know what to look for, this strategy optimises your resources. The discovery in 2012 of the Higgs boson demonstrates this: a mission considered impossible in the 1980s was accomplished with less data and less time than anticipated by the most optimistic guesses when the LHC was being designed. Machine learning played a crucial role in this.

Machine learning

Machine learning (ML) is a branch of computer science that deals with algorithms capable of accomplishing a task without being explicitly programmed to do so. Unlike traditional algorithms, which are sets of pre-determined operations, an ML algorithm is not programmed. It is trained on data, so that it can adjust itself to maximise its chances of success, as defined by a quantitative figure of merit.

To explain further, let’s use the example of a dataset of images of cats and dogs. We’ll label the cats as “0” and the dogs as “1”, and represent the images as a two-dimensional array of coloured pixels, each with a fraction of red, green and blue. Each dog or cat is now a stack of three two-dimensional arrays of numbers between 0 and 1 – essentially just the animal pictured in red, green and blue light. We would like to have a mathematical function converting this stack of arrays into a score ranging from 0 to 1. The larger the score, the higher the probability that the image is a dog. The smaller the score, the higher the probability that the image is a cat. An ML algorithm is a function of this kind, whose parameters are fixed by looking at a given dataset for which the correct labels are known. Through a training process, the algorithm is tuned to minimise the number of wrong answers by comparing its prediction to the labels.

Now replace the dogs with photons from the decay of a Higgs boson, and the cats with detector noise that is mistaken to be photons. Repeat the procedure, and you will obtain a photon-identification algorithm that you can use on LHC data to improve the search for Higgs bosons. This is what happened in the CMS experiment back in 2012. Thanks to the use of a special kind of ML algorithm called boosted decision trees, it was possible to maximise the accuracy of the Higgs-boson search, exploiting the rich information provided by the experiment’s electromagnetic calorimeter. The ATLAS collaboration developed a similar procedure to identify Higgs bosons decaying into a pair of tau leptons.

Photon and tau-lepton classifiers are both examples of supervised learning, and the success of the discovery of the Higgs boson was also a success story for applied ML. So far so good. But what about searching for new physics?

Typical examples of new physics such as supersymmetry, extra dimensions and the underlying structure for the Higgs boson have been extensively investigated at the LHC, with no evidence for them found in data. This has told us a great deal about what the particles predicted by these scenarios cannot look like, but what if the signal hypotheses are simply wrong, and we’re not looking for the right thing? This situation calls for “unsupervised” learning, where humans are not required to label data. As with supervised learning, this idea doesn’t originate in physics. Marketing teams use clustering algorithms based on it to identify customer segments. Banks use it to detect credit-card fraud by looking for anomalous access patterns in customers’ accounts. Similar anomaly detection techniques could be used at the LHC to single out rare events, possibly originating from new, previously undreamt of, mechanisms.

Unsupervised learning

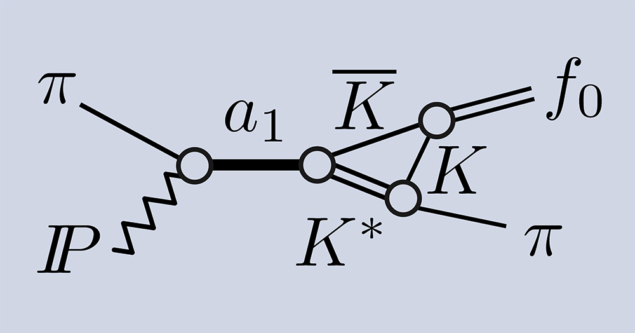

Anomaly detection is a possible strategy for keeping watch for new physics without having to specify an exact signal. A kind of unsupervised ML, it involves ranking an unlabelled dataset from the most typical to the most atypical, using a ranking metric learned during training. One of the advantages of this approach is that the algorithm can be trained on data recorded by the experiment rather than simulations. This could, for example, be a control sample that we know to be dominated by SM processes: the algorithm will learn how to reconstruct these events “exactly” – and conversely how to rank unknown processes as atypical. As a proof of principle, this strategy has already been applied to re-discover the top quark using the first open-data release by the CMS collaboration.

This approach could be used in the online data processing at the LHC and applied to the full 40 million collision events produced every second. Clustering techniques commonly used in observational astronomy could be used to highlight the recurrence of special kinds of events.

is suitable for human observation, using the t-SNE algorithm. While most new-physics events overlap with the SM events, the most anomalous populate the outlying regions. These outliers could be used to define a stream of potentially interesting events to be further scrutinised in future data-taking campaigns. Credit: E Puljak

In case a new kind of process happens in an LHC collision, but is discarded by the trigger algorithms serving the traditional physics programme, an anomaly-detection algorithm could save the relevant events, storing them in a special stream of anomalous events (see “Anomaly hunting” figure). The ultimate goal of this approach would be the creation of an “anomaly catalogue” of event topologies for further studies, which could inspire novel ideas for new-physics scenarios to test using more traditional techniques. With an anomaly catalogue, we could return to the first stage of the scientific method, and recover a data-driven alternative approach to the theory-driven investigation that we have come to rely on.

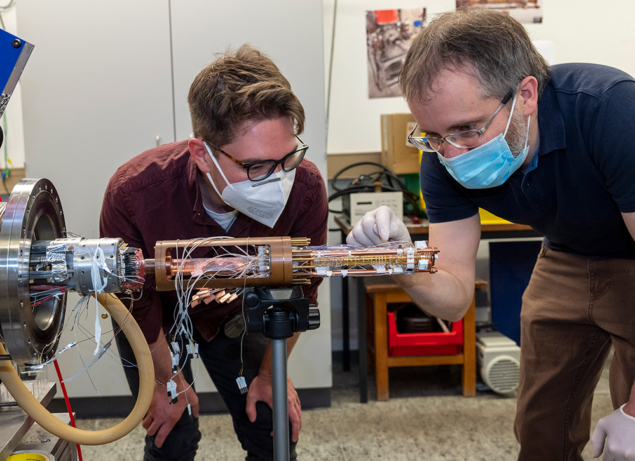

This idea comes with severe technological challenges. To apply this technique to all collision events, we would need to integrate the algorithm, typically a special kind of neural network called an autoencoder, into the very first stage of the online data selection, the level-one (L1) trigger. The L1 trigger consists of logic algorithms integrated onto custom electronic boards based on field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) – a highly parallelisable chip that serves as a programmable emulator of electronic circuits. Any L1 trigger algorithm has to run within the order of one microsecond, and take only a fraction of the available computing resources. To run in the L1 trigger system, an anomaly detection network needs to be converted into an electronic circuit that would fulfill these constraints. This goal can be met using the “hls4ml” (high-level synthesis for ML) library – a tool designed by an international collaboration of LHC physicists that exploits automatic workflows.

Computer-science collaboration

Recently, we collaborated with a team of researchers from Google to integrate the hls4ml library into Google’s “QKeras” – a tool for developing accurate ML models on FPGAs with a limited computing footprint. Thanks to this partnership, we developed a workflow that can design a ML model in concert with its final implementation on the experimental hardware. The resulting QKeras+hls4ml bundle is designed to allow LHC physicists to deploy anomaly-detection algorithms in the L1 trigger system. This approach could practically be deployed in L1 trigger systems before the end of LHC Run 3 – a powerful complement to the anomaly-detection techniques that are already being considered for “offline” data analysis on the traditionally triggered samples.

AI techniques could help the field break beyond the limits of human creativity in theory building

If this strategy is endorsed by the experimental collaborations, it could create a public dataset of anomalous data that could be investigated during the third LHC long shutdown, from 2025 to 2027. By studying those events, phenomenologists and theoretical physicists could formulate creative hypotheses about new-physics scenarios to test, potentially opening up new search directions for the High-Luminosity LHC.

Blind analyses minimise human bias if you know what to look for, but risk yielding diminishing returns when the theoretical picture is uncertain, as is the case in particle physics after the first 10 years of LHC physics. Unsupervised AI techniques such as anomaly detection could help the field break beyond the limits of human creativity in theory building. In the big-data environment of the LHC, they offer a powerful means to move the field back to data-driven discovery, after 50 years of theory-driven progress. To maximise their impact, they should be applied to every collision produced at the LHC. For that reason, we argue that anomaly-detection algorithms should be deployed in the L1 triggers of the LHC experiments, despite the technological challenges that must be overcome to make that happen.