Particle physics is at its heart a reductionistic endeavour that tries to reduce reality to its most basic building blocks. This view of nature is most evident in the search for a theory of everything – an idea that is nowadays more common in popularisations of physics than among physicists themselves. If discovered, all physical phenomena would follow from the application of its fundamental laws.

A complementary perspective to reductionism is that of emergence. Emergence says that new and different kinds of phenomena arise in large and complex systems, and that these phenomena may be impossible, or at least very hard, to derive from the laws that govern their basic constituents. It deals with properties of a macroscopic system that have no meaning at the level of its microscopic building blocks. Good examples are the wetness of water and the superconductivity of an alloy. These concepts don’t exist at the level of individual atoms or molecules, and are very difficult to derive from the microscopic laws.

As physicists continue to search for cracks in the Standard Model (SM) and Einstein’s general theory of relativity, could these natural laws in fact be emergent from a deeper reality? And emergence is not limited to the world of the very small, but by its very nature skips across orders of magnitude in scale. It is even evident, often mesmerisingly so, at scales much larger than atoms or elementary particles, for example in the murmurations of a flock of birds – a phenomenon that is impossible to describe by following the motion of an individual bird. Another striking example may be intelligence. The mechanism by which artificial intelligence is beginning to emerge from the complexity of underlying computing codes shows similarities with emergent phenomena in physics. One can argue that intelligence, whether it occurs naturally, as in humans, or artificially, should also be viewed as an emergent phenomenon.

Data compression

Renormalisable quantum field theory, the foundation of the SM, works extraordinarily well. The same is true of general relativity. How can our best theories of nature be so successful, while at the same time being merely emergent? Perhaps these theories are so successful precisely because they are emergent.

As a warm up, let’s consider the laws of thermodynamics, which emerge from the microscopic motion of many molecules. These laws are not fundamental but are derived by statistical averaging – a huge data compression in which the individual motions of the microscopic particles are compressed into just a few macroscopic quantities such as temperature. As a result, the laws of thermodynamics are universal and independent of the details of the microscopic theory. This is true of all the most successful emergent theories; they describe universal macroscopic phenomena whose underlying microscopic descriptions may be very different. For instance, two physical systems that undergo a second-order phase transition, while being very different microscopically, often obey exactly the same scaling laws, and are at the critical point described by the same emergent theory. In other words, an emergent theory can often be derived from a large universality class of many underlying microscopic theories.

Successful emergent theories describe universal macroscopic phenomena whose underlying microscopic descriptions may be very different

Entropy is a key concept here. Suppose that you try to store the microscopic data associated with the motion of some particles on a computer. If we need N bits to store all that information, we have 2N possible microscopic states. The entropy equals the logarithm of this number, and essentially counts the number of bits of information. Entropy is therefore a measure of the total amount of data that has been compressed. In deriving the laws of thermodynamics, you throw away a large amount of microscopic data, but you at least keep count of how much information has been removed in the data-compression procedure.

Emergent quantum field theory

One of the great theoretical-physics paradigm shifts of the 20th century occurred when Kenneth Wilson explained the emergence of quantum field theory through the application of the renormalisation group. As with thermodynamics, renormalisation compresses microscopic data into a few relevant parameters – in this case, the fields and interactions of the emergent quantum field theory. Wilson demonstrated that quantum field theories appear naturally as an effective long-distance and low-energy description of systems whose microscopic definition is given in terms of a quantum system living on a discretised spacetime. As a concrete example, consider quantum spins on a lattice. Here, renormalisation amounts to replacing the lattice by a coarser lattice with fewer points, and redefining the spins to be the average of the original spins. One then rescales the coarser lattice so that the distance between lattice points takes the old value, and repeats this step many times. A key insight was that, for quantum statistical systems that are close to a phase transition, you can take a continuum limit in which the expectation values of the spins turn into the local quantum fields on the continuum spacetime.

This procedure is analogous to the compression algorithms used in machine learning. Each renormalisation step creates a new layer, and the algorithm that is applied between two layers amounts to a form of data compression. The goal is similar: you only keep the information that is required to describe the long-distance and low-energy behaviour of the system in the most efficient way.

So quantum field theory can be seen as an effective emergent description of one of a large universality class of many possible underlying microscopic theories. But what about the SM specifically, and its possible supersymmetric extensions? Gauge fields are central ingredients of the SM and its extensions. Could gauge symmetries and their associated forces emerge from a microscopic description in which there are no gauge fields? Similar questions can also be asked about the gravitational force. Could the curvature of spacetime be explained from an emergent perspective?

String theory seems to indicate that this is indeed possible, at least theoretically. While initially formulated in terms of vibrating strings moving in space and time, it became clear in the 1990s that string theory also contains many more extended objects, known as “branes”. By studying the interplay between branes and strings, an even more microscopic theoretical description was found in which the coordinates of space and time themselves start to dissolve: instead of being described by real numbers, our familiar (x, y, z) coordinates are replaced by non-commuting matrices. At low energies, these matrices begin to commute, and give rise to the normal spacetime with which we are familiar. In these theoretical models it was found that both gauge forces and gravitational forces appear at low energies, while not existing at the microscopic level.

While these models show that it is theoretically possible for gauge forces to emerge, there is at present no emergent theory of the SM. Such a theory seems to be well beyond us. Gravity, however, being universal, has been more amenable to emergence.

Emergent gravity

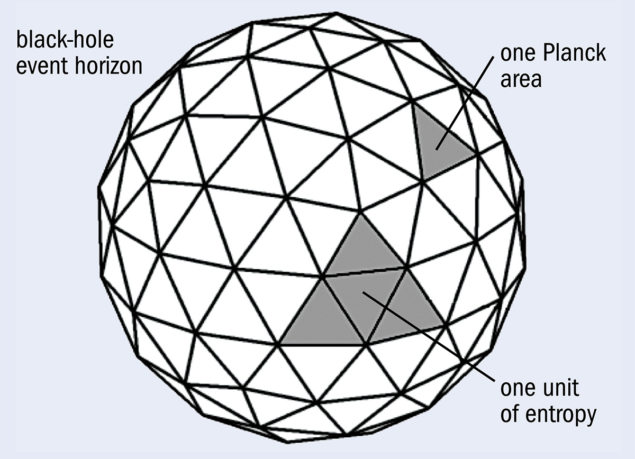

In the early 1970s, a group of physicists became interested in the question: what happens to the entropy of a thermodynamic system that is dropped into a black hole? The surprising conclusion was that black holes have a temperature and an entropy, and behave exactly like thermodynamic systems. In particular, they obey the first law of thermodynamics: when the mass of a black hole increases, its (Bekenstein–Hawking) entropy also increases.

The correspondence between the gravitational laws and the laws of thermodynamics does not only hold near black holes. You can artificially create a gravitational field by accelerating. For an observer who continues to accelerate, even empty space develops a horizon, from behind which light rays will not be able to catch up. These horizons also carry a temperature and entropy, and obey the same thermodynamic laws as black-hole horizons.

It was shown by Stephen Hawking that the thermal radiation emitted from a black hole originates from pair creation near the black-hole horizon. The properties of the pair of particles, such as spin and charge, are undetermined due to quantum uncertainty, but if one particle has spin up (or positive charge), then the other particle must have spin down (or negative charge). This means that the particles are quantum entangled. Quantum entangled pairs can also be found in flat space by considering accelerated observers.

Crucially, even the vacuum can be entangled. By separating spacetime into two parts, you can ask how much entanglement there is between the two sides. The answer to this was found in the last decade, through the work of many theorists, and turns out to be rather surprising. If you consider two regions of space that are separated by a two-dimensional surface, the amount of quantum entanglement between the two sides turns out to be precisely given by the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy formula: it is equal to a quarter of the area of the surface measured in Planck units.

Holographic renormalisation

The AdS/CFT correspondence incorporates a principle called “holography”: the gravitational physics inside a region of space emerges from a microscopic description that, just like a hologram, lives on a space with one less dimension and thus can be viewed as living on the boundary of the spacetime region. The extra dimension of space emerges together with the gravitational force through a process called “holographic renormalisation”. One successively adds new layers of spacetime. Each layer is obtained from the previous layer through “coarse-graining”, in a similar way to both renormalisation in quantum field theory and data-compression algorithms in machine learning.

Unfortunately, our universe is not described by a negatively curved spacetime. It is much closer to a so-called de Sitter spacetime, which has a positive curvature. The main difference between de Sitter space and the negatively curved anti-de Sitter space is that de Sitter space does not have a boundary. Instead, it has a cosmological horizon whose size is determined by the rate of the Hubble expansion. One proposed explanation for this qualitative difference is that, unlike for negatively curved spacetimes, the microscopic quantum state of our universe is not unique, but secretly carries a lot of quantum information. The amount of this quantum information can once again be counted by an entropy: the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy associated with the cosmological horizon.

This raises an interesting prospect: if the microscopic quantum data of our universe may be thought of as many entangled qubits, could our current theories of spacetime, particles and forces emerge via data compression? Space, for example, could emerge by forgetting the precise way in which all the individual qubits are entangled, but only preserving the information about the amount of quantum entanglement present in the microscopic quantum state. This compressed information would then be stored in the form of the areas of certain surfaces inside the emergent curved spacetime.

In this description, gravity would follow for free, expressed in the curvature of this emergent spacetime. What is not immediately clear is why the curved spacetime would obey the Einstein equations. As Einstein showed, the amount of curvature in spacetime is determined by the amount of energy (or mass) that is present. It can be shown that his equations are precisely equivalent to an application of the first law of thermodynamics. The presence of mass or energy changes the amount of entanglement, and hence the area of the surfaces in spacetime. This change in area can be computed and precisely leads to the same spacetime curvature that follows from the Einstein equations.

The idea that gravity emerges from quantum entanglement goes back to the 1990s, and was first proposed by Ted Jacobson. Not long afterwards, Juan Maldacena discovered that general relativity can be derived from an underlying microscopic quantum theory without a gravitational force. His description only works for infinite spacetimes with negative curvature called anti-de Sitter (or AdS–) space, as opposed to the positive curvature we measure. The microscopic description then takes the form of a scale-invariant quantum field theory – a so-called conformal field theory (CFT) – that lives on the boundary of the AdS–space (see “Holographic renormalisation” panel). It is in this context that the connection between vacuum entanglement and the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy, and the derivation of the Einstein equations from entanglement, are best understood. I have also contributed to these developments in a paper in 2010 that emphasised the role of entropy and information for the emergence of the gravitational force. Over the last decade a lot of progress has been made in our understanding of these connections, in particular the deep connection between gravity and quantum entanglement. Quantum information has taken centre stage in the most recent theoretical developments.

Emergent intelligence

But what about viewing the even more complex problem of human intelligence as an emergent phenomenon? Since scientific knowledge is condensed and stored in our current theories of nature, the process of theory formation can itself be viewed as a very efficient form of data compression: it only keeps the information needed to make predictions about reproducible events. Our theories provide us with a way to make predictions with the fewest possible number of free parameters.

The same principles apply in machine learning. The way an artificial-intelligence machine is able to predict whether an image represents a dog or a cat is by compressing the microscopic data stored in individual pixels in the most efficient way. This decision cannot be made at the level of individual pixels. Only after the data has been compressed and reduced to its essence does it becomes clear what the picture represents. In this sense, the dog/cat-ness of a picture is an emergent property. This is even true for the way humans process the data collected by our senses. It seems easy to tell whether we are seeing or hearing a dog or a cat, but underneath, and hidden from our conscious mind, our brains perform a very complicated task that turns all the neural data that come from our eyes and ears into a signal that is compressed into a single outcome: it is a dog or a cat.

Emergence is often summarised with the slogan “the whole is more than the sum of its parts”

Can intelligence, whether artificial or human, be explained from a reductionist point of view? Or is it an emergent concept that only appears when we consider a complex system built out of many basic constituents? There are arguments in favour of both sides. As human beings, our brains are hard-wired to observe, learn, analyse and solve problems. To achieve these goals the brain takes the large amount of complex data received via our senses and reduces it to a very small set of information that is most relevant for our purposes. This capacity for efficient data compression may indeed be a good definition for intelligence, when it is linked to making decisions towards reaching a certain goal. Intelligence defined in this way is exhibited in humans, but can also be achieved artificially.

Artificially intelligent computers beat us at problem solving, pattern recognition and sometimes even in what appears to be “generating new ideas”. A striking example is DeepMind’s AlphaZero, whose chess rating far exceeds that of any human player. Just four hours after learning the rules of chess, AlphaZero was able to beat the strongest conventional “brute force” chess program by coming up with smarter ideas and showing a deeper understanding of the game. Top grandmasters use its ideas in their own games at the highest level.

In its basic material design, an artificial-intelligence machine looks like an ordinary computer. On the other hand, it is practically impossible to explain all aspects of human intelligence by starting at the microscopic level of the neurons in our brain, let alone in terms of the elementary particles that make up those neurons. Furthermore, the intellectual capability of humans is closely connected to the sense of consciousness, which most scientists would agree does not allow for a simple reductionist explanation.

Emergence is often summarised with the slogan “the whole is more than the sum of its parts” – or as condensed-matter theorist Phil Anderson put it, “more is different”. It counters the reductionist point of view, reminding us that the laws that we think to be fundamental today may in fact emerge from a deeper underlying reality. While this deeper layer may remain inaccessible to experiment, it is an essential tool for theorists of the mind and the laws of physics alike.