Stuart Raby has written a modern, comprehensive textbook on quantum field theory, the Standard Model (SM) and its possible extensions. The focus of the book is on symmetries, and it contains a wealth of recent experimental results on Higgs and neutrino physics, which sets it apart from other textbooks addressing the same audience. It is published at a time when the incredible success story of the SM has come to a close with the discovery of the Higgs boson, and when the upcoming neutrino experiments promise to probe beyond-the-SM physics.

Raby is the author of some of the most important papers on supersymmetric grand unified theories and the book reflects that. It is no easy task to cover such a wide range of topics, from the basics of group theory to very advanced concepts such as gauge and gravity-mediated supersymmetry breaking, in one book. Raby devotes 120 pages to the basics of group theory, representations of the Poincaré group and the construction of the S matrix to provide the necessary foundations for the introduction to quantum electrodynamics in part III. Parts IV–VI introduce the reader to discrete symmetries, flavour symmetries and spontaneous symmetry breaking. Next, Raby describes two “Roads to the Standard Model” following the development of quantum chromodynamics and of electroweak theory, before arriving at the SM in part IX. The remaining parts deal with neutrino physics, grand unified theories and the minimal supersymmetric SM.

There are no omissions topic-wise, which makes the book very comprehensive. This comes at a price, however. In several places, complicated topics are discussed with only the most minimal of context, reading like a collection of equations rather than a textbook. Two examples of this are the discussion of causality for fermionic fields or the step from global to local supersymmetry, to which the author devotes only half a page each. In other places, more cross-referencing would improve legibility. For example, the chapter on SU(5) grand unified theory does not mention the automatic cancellation of gauge anomalies, a topic previously introduced in the context of the SM.

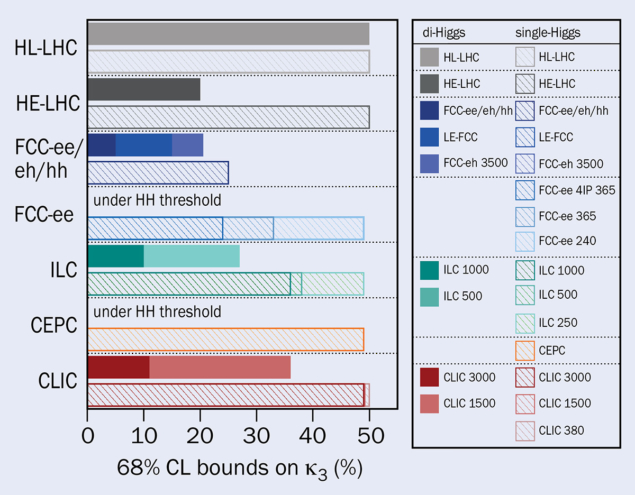

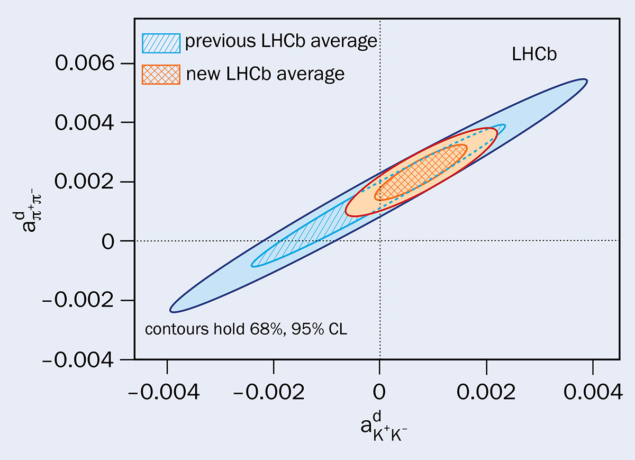

The use of materials is very distinctive. I doubt there is another book on the market that presents the reader with such a wealth of plots, figures and sketches, including recent experimental results on all the important topics discussed. The most important plots are reproduced in 12 pages of colour tables in the centre. There are exercises for the first five parts and a single Mathematica notebook is printed for Wigner rotations. Another distinguishing feature are the detailed suggested projects to use during a two-term course based on the book.

A very useful resource for designing a lecture of quantum field theory and beyond-the-SM physics

Although advertised as useful for both theorists and experimentalists, it is undeniably a book written from a theorist’s perspective. This becomes most clear in the latter parts, where relevant sections of the plots presenting experimental results remain unexplained. That being said, other very important experimental topics are explained, which you will not find in other textbooks about the SM. Raby explains how the anomalous magnetic moments of the electron and the muon are measured, and goes into quite some detail on neutrino experiments.

The book would benefit from improved editing. For example, the units are sometimes in italics, sometimes not, some equations are double tagged, some plots do not have axes labels, and there is inconsistent use of wavy and curly lines in the Feynman diagrams. Raby does make good use of references though, and points the reader to other textbooks and original literature; although the index needs to be extended significantly to be useful.

I recommend this book for advanced undergraduates, graduate students and lecturers. It provides a very useful resource for designing a lecture of quantum field theory and beyond-the-SM physics, and the amount of material covered is impressive and comprehensive. Beginners might be overwhelmed by Raby’s compact style , so I would recommend those who are new to quantum field theory to read a more accessible textbook in parallel.

Krzysztof Brodzinski is a senior staff member in the cryogenics group at the technology department at CERN. He is a mechanical engineer with a specialisation in refrigeration equipment, and graduated from Cracow University of Technology in Poland. Krzysztof joined the LHC cryogenic design team in 2001, has been a member of the cryogenic operation team since 2009 and in 2019 was mandated as a section leader of the cryogenic operation team for the LHC, ATLAS and CMS. He is also involved in the engineering of the cryogenic system for the HiLumi LHC RF deflecting cavities project, as well as participating in the ongoing FCC cryogenics study.

Krzysztof Brodzinski is a senior staff member in the cryogenics group at the technology department at CERN. He is a mechanical engineer with a specialisation in refrigeration equipment, and graduated from Cracow University of Technology in Poland. Krzysztof joined the LHC cryogenic design team in 2001, has been a member of the cryogenic operation team since 2009 and in 2019 was mandated as a section leader of the cryogenic operation team for the LHC, ATLAS and CMS. He is also involved in the engineering of the cryogenic system for the HiLumi LHC RF deflecting cavities project, as well as participating in the ongoing FCC cryogenics study.