Image credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.

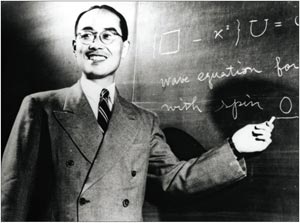

This year is the centenary of the birth of Hideki Yukawa who, in 1935, proposed the existence of the particle now known as the π meson, or pion. To celebrate, the International Nuclear Physics Conference took place in Japan on 3–8 June – 30 years after the previous one in 1977 – with an opening ceremony honoured by the presence of the Emperor and Empress. In his speech, the Emperor noted that Yukawa – the first Nobel Laureate in Japanese science – is an icon not only for young Japanese scientists but for everybody in Japan. Yukawa’s particle led to a gold mine in physics linked to the pion’s production, decay and intrinsic structure.This gold mine continues to be explored today. The present frontier is the quark–gluon-coloured-world (QGCW), whose properties could open new horizons in understanding nature’s logic.

Production

In his 1935 paper, Yukawa proposed searching for a particle with a mass between the light electron and the heavy nucleon (proton or neutron). He deduced this intermediate value – the origin of the name “mesotron”, later abbreviated to meson – from the range of the nuclear forces (Yukawa 1935). The search for cosmic-ray particles with masses between those of the electron and the nucleon became a hot topic during the 1930s thanks to this work.

On 30 March 1937, Seth Neddermeyer and Carl Anderson reported the first experimental evidence, in cosmic radiation, for the existence of positively and negatively charged particles heavier and with more penetrating power than electrons, but much less massive than protons (Neddermeyer and Anderson 1937). Then, at the meeting of the American Physical Society on 29 April, J C Street and E C Stevenson presented the results of an experiment that gave, for the first time, a mass value of 130 electron masses (me) with 25% uncertainty (Street and Stevenson 1937). Four months later, on 28 August, Y Nishina, M Takeuchi and T Ichimiya submitted to Physical Review their experimental evidence for a positively charged particle with mass between 180 me and 260 me (Nishina et al. 1937).

Image credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.

The following year, on 16 June, Neddermeyer and Anderson reported the observation of a positively charged particle with a mass of about 240 me (Neddermeyer and Anderson 1938), and on 31 January 1939, Nishina and colleagues presented the discovery of a negative particle with mass (170 ± 9) me (Nishina et al. 1939). In this paper, the authors improved the mass measurement of their previous particle (with positive charge) and concluded that the result obtained, m = (180 ± 20) me, was in good agreement with the value for the negative particle. Yukawa’s meson theory of the strong nuclear forces thus appeared to have excellent experimental confirmation. His idea sparked an enormous interest in the properties of cosmic rays in this “intermediate” range; it was here that a gold mine was to be found.

In Italy, a group of young physicists – Marcello Conversi, Ettore Pancini and Oreste Piccioni – decided to study how the negative mesotrons were captured by nuclear matter. Using a strong magnetic field to separate clearly the negative from the positive rays, they discovered that the negative mesotrons were not strongly coupled to nuclear matter (Conversi et al. 1947). Enrico Fermi, Edward Teller and Victor Weisskopf pointed out that the decay time of these negative particles in matter was 12 powers of 10 longer than the time needed for Yukawa’s particle to be captured by a nucleus via the nuclear forces (Fermi et al. 1947). They introduced the symbol μ, for mesotron, to specify the nature of the negative cosmic-ray particle being investigated.

In addition to Conversi, Pancini, Piccioni and Fermi, another Italian, Giuseppe Occhialini, was instrumental in understanding the gold mine that Yukawa had opened. This further step required the technology of photographic emulsion, in which Occhialini was the world expert. With Cesare Lattes, Hugh Muirhead and Cecil Powell, Occhialini discovered that the negative μ mesons were the decay products of another mesotron, the “primary” one – the origin of the symbol π (Lattes et al. 1947). This is in fact the particle produced by the nuclear forces, as Yukawa had proposed, and its discovery finally provided the nuclear “glue”. However this was not the end of the gold mine.

The decay-chain

The discovery by Lattes, Muirhead, Occhialini and Powell allowed the observation of the complete decay-chain π → μ → e, and this became the basis for understanding the real nature of the cosmicray particles observed during 1937–1939, which Conversi, Pancini and Piccioni had proved to have no nuclear coupling with matter. The gold mine not only contained the π meson but also the μ meson. This opened a completely unexpected new field, the world of particles known as leptons, the first member being the electron. The second member, the muon (μ), is no longer called a meson, but is now correctly called a lepton. The muon has the same electromagnetic properties as the electron, but a mass 200 times heavier and no nuclear charge. This incredible property prompted Isidor Rabi to make the famous statement “Who ordered that?” as reported by T D Lee (Barnabei et al. 1998).

In the 1960s, it became clear that there would not be so many muons were it not for the π meson. Indeed, if another meson like the π existed in the “heavy” mass region, a third lepton – heavier than the muon – would not have been so easily produced in the decays of the heavy meson because this meson would decay strongly into many π mesons. The remarkable π–μ case was unique. So, the absence of a third lepton in the many final states produced in high-energy interactions at proton accelerators at CERN and other laboratories, was not to be considered a fundamental absence, but a consequence of the fact that a third lepton could only be produced via electromagnetic processes, as for example via time-like photons in pp or e+e– annihilation. The uniqueness of the π–μ case therefore sparked the idea of searching for a third lepton in the appropriate production processes (Barnabei et al. 1998).

Once again, this was still not the end of the gold mine, as understanding the decay of Yukawa’s particle led to the field of weak forces. The discovery of the leptonic world opened the problem of the universal Fermi interactions, which became a central focus of the physics community in the late 1940s. Lee, M Rosenbluth and C N Yang proposed the existence of an intermediate boson, called W as it was the quantum of the weak forces. This particle later proved to be the source of the breaking of parity (P) and charge conjugation (C) symmetries in weak interactions.

In addition, George Rochester and Clifford Butler in Patrick Blackett’s laboratory in Manchester discovered another meson – later dubbed “strange” – in 1947, the same year of the π meson discovery. This meson, called θ, decayed into two pions. It took nearly 10 years to find out that the θ and another meson called τ, with equal mass and lifetime but decaying into three pions, were not two different mesons but two different decay modes of the same particle, the K meson. Lee and Yang solved the famous θ–τ puzzle in 1956, when they proved that no experimental evidence existed to establish the validity of P and C invariance in weak interactions; the experimental evidence came immediately after.

The violation of P and C generated the problem of PC conservation, and therefore that of time-reversal (T) invariance (through the PCT theorem). This invariance law was proposed by Lev Landau, while Lee, Reinhard Oehme and Yang remarked on the lack of experimental evidence for it. Proof that they were on the right experimental track came in 1964, when James Christenson, James Cronin, Val Fitch and René Turlay discovered that the meson called K02 also decayed into two Yukawa mesons. Rabi’s famous statement became “Who ordered all that?” – “all” being the rich contents of the Yukawa gold mine.

A final comment on the “decay seam” of the gold mine concerns the decay of the neutral Yukawa meson, π0 → γγ. This generated the ABJ anomaly, the celebrated chiral anomaly named after Steven L Adler, John Bell, and Roman Jackiw, which had remarkable consequences in the area of non-Abelian forces. One of these is the “anomaly-free condition”, an important ingredient in theoretical model building, which explains why the number of quarks in the fundamental fermions must equal the number of leptons. This allowed the theoretical prediction of the heaviest quark – the top-quark, t – in addition to the b quark in the third family of elementary fermions.

Intrinsic structure

The Yukawa particle is made of a pair of the lightest, nearly- massless, elementary fermions: the up and down quarks. This allows us to understand why chirality-invariance – a global symmetry property – should exist in strong interactions. It is the spontaneous breaking of this global symmetry that generates the Nambu–Goldstone boson. The intrinsic structure of the Yukawa particle needs the existence of a non-Abelian fundamental force – the QCD force – acting between the constituents of the π meson (quarks and gluons) and originating in a gauge principle. Thanks to this principle, the QCD quantum is a vector and does not destroy chirality-invariance.

To understand the non-zero mass of the Yukawa meson, another feature of the non-Abelian force of QCD had to exist: instantons. Thanks to instantons, chirality-invariance can also be broken in a non-spontaneous way. If this were not the case, the π could not be as “heavy” as it is; it would have to be nearly massless. So, can a pseudoscalar meson exist with a mass as large as that of the nucleon? The answer is “yes”: its name is η’ and it represents the final point in the gold mine started with the π meson. Its mass is not intermediate, but is nearly the same as the nucleon mass.

The η’ is a pseudoscalar meson, like the π, and was originally called X0. Very few believed that it could be a pseudoscalar because its mass and width were too big and there was no sign of its 2γ decay mode. This missing decay mode initially prevented the X0 from being considered the ninth singlet member of the pseudoscalar SU(3) uds flavour multiplet of Murray Gell-Mann and Yuval Ne’eman. However, the eventual discovery of the 2γ decay mode strongly supported the pseudoscalar nature of the X0, and once this was established, its gluon content became theoretically predicted through the QCD istantons.

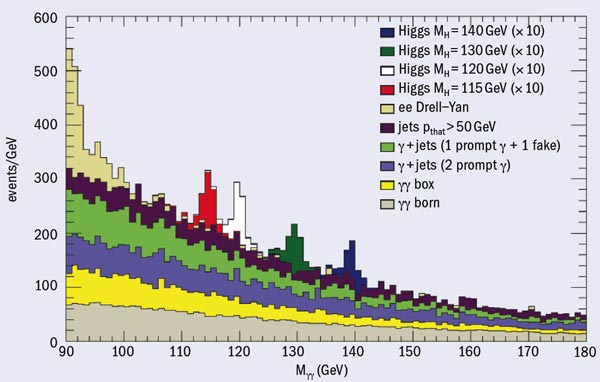

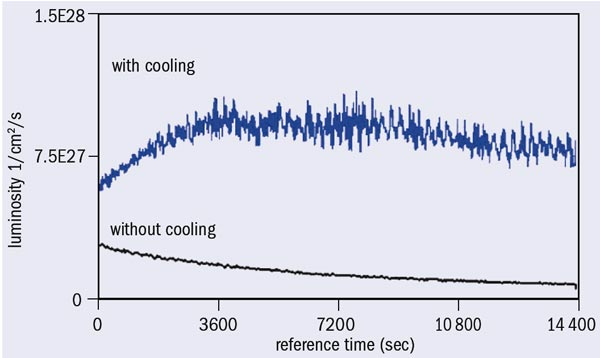

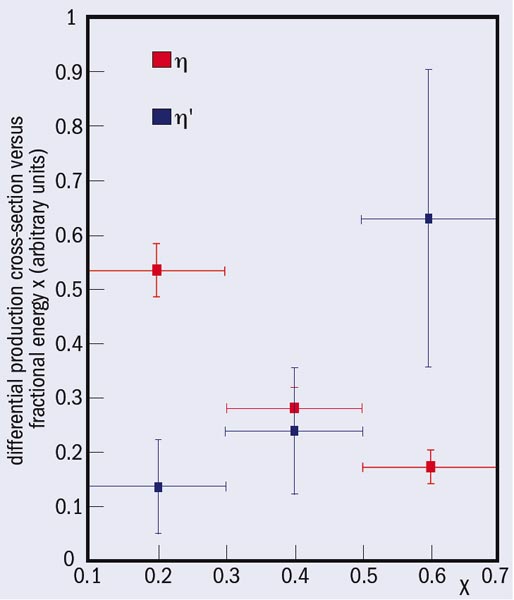

If the η’ has an important gluon component, we should expect to see a typical QCD non-perturbative effect: leading production in gluon-induced jets. This is exactly the effect that has been observed in the production of the η’ mesons in gluon-induced jets, while it is not present in η production (figure 1).

The interesting point here is that it appears that the η’ is the lowest pseudoscalar state having the most important contribution from the quanta of the QCD force. The η’ is thus the particle most directly linked with the original idea of Yukawa, who was advocating the existence of a quantum of the nuclear force field; the η’ is the Yukawa particle of the QCD era. Seventy two years after Yukawa’s original idea we have found that his meson, the π, has given rise to a fantastic development in our thinking, the last step being the η’ meson.

The quark–gluon-coloured world

There is still a further lesson from Yukawa’s gold mine: the impressive series of totally unexpected discoveries. Let me quote just three of them, starting with the experimental evidence for a cosmic-ray particle that was believed to be Yukawa’s meson, which turned out to be a lepton: the muon. Then, the decay-chain π → μ → e was found to break the symmetry laws of parity and charge conjugation. Third, the intrinsic structure of the Yukawa particle was found to be governed by a new fundamental force of nature, the strong force described by QCD.

This is perfectly consistent with the great steps in physics: all totally unexpected. Such totally unexpected events, which historians call Sarajevo-type-effects, characterize “complexity”. A detailed analysis shows that the experimentally observable quantities that characterize complexity in a given field exist in physics; the Yukawa gold mine is a proof. This means that complexity exists at the fundamental level, and that totally unexpected effects should show up in physics – effects that are impossible to predict on the basis of present knowledge. Where these effects are most likely to be, no one knows. All we are sure of is that new experimental facilities are needed, like those that are already under construction around the world.

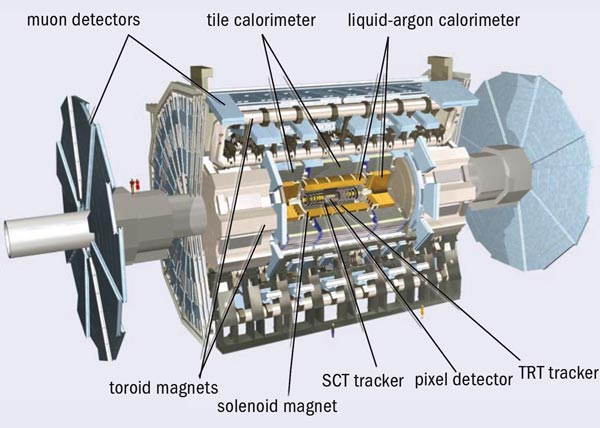

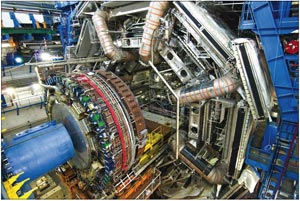

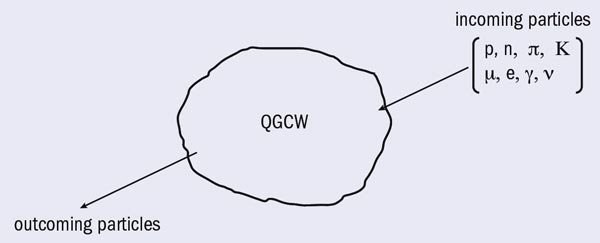

With the advent of the LHC at CERN, it will be possible to study the properties of the quark–gluon coloured world (QGCW). This is totally different from our world made of QCD vacuum with colourless baryons and mesons because the QGCW contains all the states allowed by the SU(3)c colour group. To investigate this world, Yukawa would tell us to search for specific effects arising from the fact that the colourless condition is avoided. Since the colourless condition is not needed, the number of possible states in the QGCW is far greater than the number of colourless baryons and mesons that have been built so far in all our laboratories.

So, a first question is: what are the consequences for the properties of the QGCW? A second question concerns light quarks versus heavy quarks. Are the coloured quark masses in the QGCW the same as the values we derive from the fact that baryons and mesons need to be colourless? It could be that all six quark flavours are associated with nearly “massless” states, similar to those of the u and d quarks. In other words, the reason why the top quark appears to be so heavy (around 200 GeV) could be the result of some, so far unknown, condition related to the fact that the final state must be QCD-colourless. We know that confinement produces masses of the order of a giga-electron-volt. Therefore, according to our present understanding, the QCD colourless condition cannot explain the heavy quark mass. However, since the origin of the quark masses is still not known, it cannot be excluded that in a QCD coloured world, the six quarks are all nearly massless and that the colourless condition is “flavour” dependent. If this was the case, QCD would not be “flavour-blind” and this would be the reason why the masses we measure are heavier than the effective coloured quark masses. In this case, all possible states generated by the “heavy” quarks would be produced in the QGCW at a much lower temperature than is needed in our world made of baryons and mesons, i.e. QCD colourless states. Here again, we should try to see if new effects could be detected due to the existence, at relatively low temperatures in QGCW physics, of all flavours, including those that might exist in addition to the six so far detected.

A third question concerns effects on the thermodynamic properties of the QGCW. Are these properties going to be along the “extensivity” or “non-extensivity” conditions? With the enormous number of QCD open-colour-states allowed in the QGCW, many different phase transitions could take place and a vast variety of complex systems should show up. The properties of this “new world” should open unprecedented horizons in understanding the ways of nature’s logic.

A fourth, related problem would be to derive the equivalent Stefan–Boltzmann radiation law for the QGCW. In classical thermodynamics, the relation between energy density at emission, U, and the temperature of the source, T, is U = sT4 – where s is a constant. In the QGCW, the correspondence should be U = pT and T = the average energy in the centre-of-momentum system, where pT is the transverse momentum. In the QGCW, the production of “heavy” flavours could be studied as functions of pT and E. The expectation is that pT = cE4, where c is a constant, and any deviation would be extremely important. The study of the properties of the QGCW should produce the correct mathematical structure to describe the QGCW. The same mathematical formalism should allow us to go from QGCW to the physics of baryons and mesons and from there to a more restricted component, namely nuclear physics, where all properties of the nuclei should finally find a complete description.

The last lesson from Yukawa

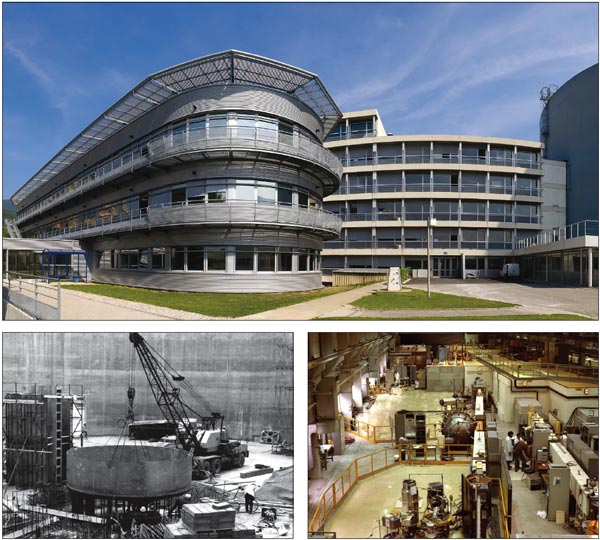

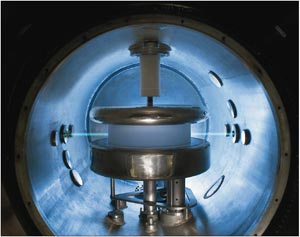

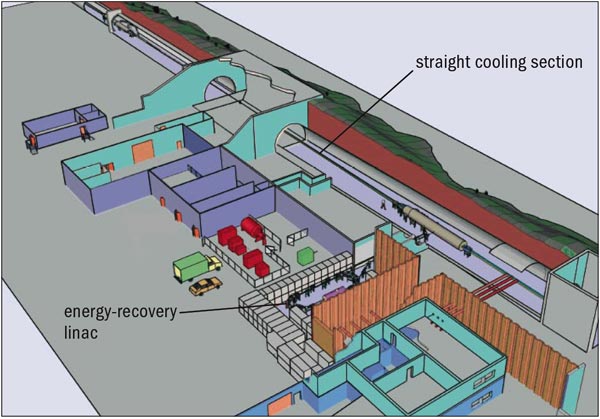

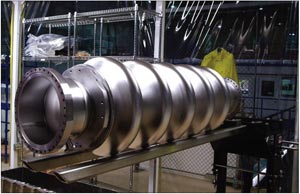

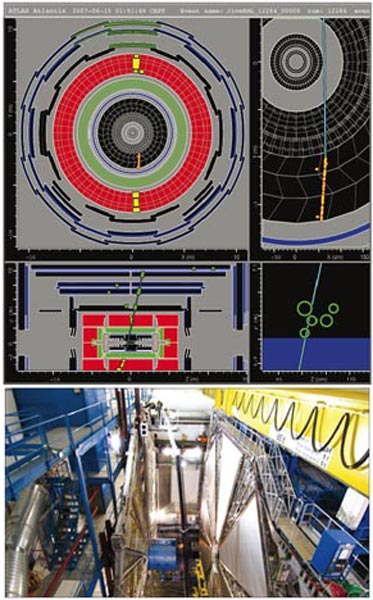

With the advent of the LHC, the development of a new technology should be able to implement collisions between different particle states (p, n, π, K, μ, e, γ, ν) and the QGCW in order to study the properties of this new world. Figure 2 gives an example of how to study the QGCW, using beams of known particles. A special set of detectors measures the properties of the outgoing particles. The QGCW is produced in a collision between heavy ions (208Pb82+) at the maximum energy available, i.e. 1150 TeV and a design luminosity of 1027 cm–2 s–1. For this to be achieved, CERN needs to upgrade the ion injector chain comprising Linac3, the Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR), the PS and the SPS. Once the lead–lead collisions are available, the problem will be to synchronize the “proton” beam with the QGCW produced. This problem is being studied at the present time. The detector technology is also under intense R&D since the synchronization needed is at a very high level of precision.

Totally unexpected effects should show up if nature follows complexity at the fundamental level. However, as with Yukawa’s gold mine that was first opened 72 years ago, new discoveries will only be made if the experimental technology is at the forefront of our knowledge. Cloud-chambers, photographic emulsions, high-power magnetic fields and powerful particle accelerators and associated detectors were needed for the all the unexpected discoveries linked to Yukawa’s particle. This means that we must be prepared with the most advanced technology for the discovery of totally unexpected events. This is Yukawa’s last lesson for us.

This article is based on a plenary lecture given at the opening session of the Symposium for the Centennial Celebration of Hideki Yukawa at the International Nuclear Physics Conference in Tokyo, 3–8 June 2007.