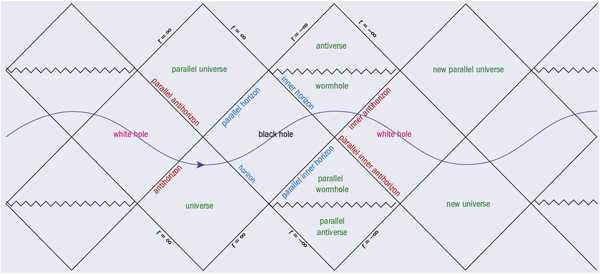

Albert Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves, faint ripples in space–time, in his general theory of relativity. They are generated by catastrophic events of astronomical objects that typically have the mass of stars. The most predictable generators of such waves are likely to be binary systems, black holes and neutron stars that spiral inwards and coalesce. However, there are many other possible sources, such as: stellar collapses that result in neutron stars and black holes (supernova explosions); rotating asymmetric neutron stars, such as pulsars; black-hole inter-actions; and the violent physics at the birth of the early universe.

In a similar way that a modulated radio signal can carry the sound of a song, these gravitational-wave ripples precisely reproduce the movement of the colliding masses that generated them. Therefore, a gravitational-wave observatory that senses the space–time ripples is actually transducing the motion of faraway stars. The great challenge is that these ripples are a strain of space (a change in length for each unit length) of the order of 10–22 to 10–23 – tremors so small that they are buried by the natural vibrations of everyday objects. As inconspicuous as a rain drop in a waterfall, they are difficult to detect.

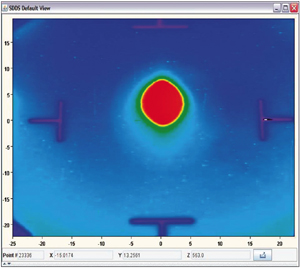

Image credit: INFN/EGO.

During the past few years, a handful of gravitational-wave projects have dared to make a determined attempt to detect these ripples. The Italian–French Virgo project (figure 1), the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the US, the British–German GEO600 project and the TAMA project in Japan have all constructed gravitational-wave observatories of impressive size and ambition. Several years ago, the GEO team joined the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC) to analyse the data collected from the two interferometers. Recently the Virgo Collaboration has been reinforced by a Dutch group, from Nikhef, Amsterdam.

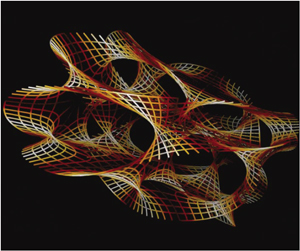

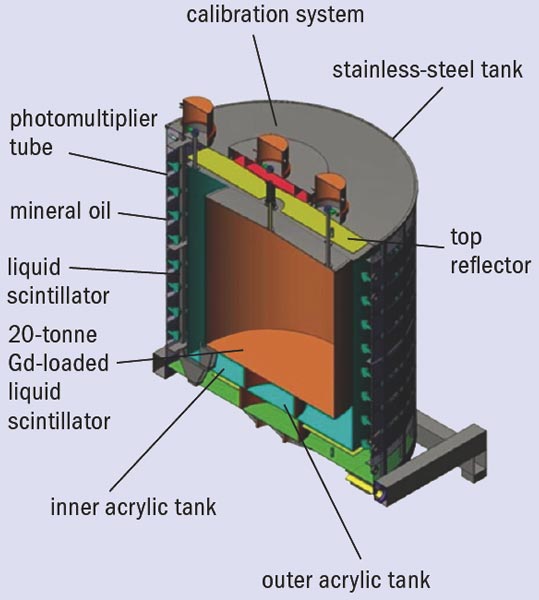

The gravitational-wave observatories are based on kilometre-length, L-shaped Michelson interferometers in which powerful and stable laser beams precisely measure this differential distance using heavy suspended mirrors that act as test masses (see figure 2). The space–time waves “drag” the test masses in the interferometer, in effect transducing (at a greatly reduced scale) the movement of the dying stars millions of parsecs away, much in the way that ears transduce sound waves into nerve impulses.

The main problem in gravitational-wave detection is that the largest expected waves from astrophysical objects will strain space–time by a factor of 10–22, resulting in movements of 10–18 to 10–19 m of the test masses on the kilometre-length interfer-ometer arms. This is smaller than a thousandth of a proton diameter, and this signal is so small that Einstein, after predicting the existence of gravitational waves, also predicted that they would never be susceptible to detection.

To surmount this challenge requires seismic isolators with enormous rejection factors to ensure that the suspended mirrors are more “quiet” than the predicted signal that they lie in wait to perceive (the typical motion of the Earth’s crust, in the absence of earthquakes, is of the order of a micrometre at 1 Hz). The instruments use extremely stable and powerful laser beams to measure the mirror separations with the required precision, but without “kicking” them with a radiation pressure exceeding the sought-after signal. The mirrors being used are marvellous, state-of-the-art constructions, and the thermal motion on their surface is more hushed than the signal amplitude. All of this is housed in large diameter (1.2 m for Virgo and LIGO) ultra-high vacuum (UHV) tubes that bisect the countryside. In fact, the vacuum pipes represent the largest UHV systems on Earth, and their volume dwarfs the volume of the longest particle-collider pipes.

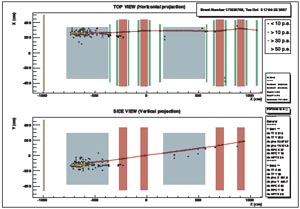

The detectors are extremely complex and difficult to tune. The installation of the LIGO interferometers finished in 2000 and complete installation of Virgo followed in 2003. Both instruments then went through several years of tuning, with LIGO reaching its design sensitivity about a year ago and Virgo fast approaching its own design target (figure 3).

Image credit: J Kern/LIGO.

On 22 May, a press conference in Cascina, Pisa, announced the first Virgo science run, as well as the first joint Virgo–LIGO data collection. That week also saw the first meeting of Virgo and the LSC in Europe. It was a momentous occasion for the entire field of gravitational-wave detection. Although the LIGO network was already into its fifth science run, which had started in November 2005, many in the community saw the announcement as marking the birth of a global gravitational-wave detector network.

Image credit: Joan Centrella, Gravitational Astrophysics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

The collaborative first and fifth science runs of Virgo and LIGO, respectively, ended on 1 October. The effort proved to be a tremendous success, demonstrating that it is possible to operate gravitational-wave observatories with excellent sensitivity and solid reliability for prolonged periods. The accumulated LIGO data amount to an effective full-year of observation at design sensitivity with all three LIGO interferometers in coincident operation, and the four-month-long joint run produced coincidence data between the two observatories with high efficiency. Although no gravitational waves were detected, the collected data are being analysed and will produce upper limits and other astrophysically significant results.

Running gravitational-wave detectors in a network has a fundamental importance related to the goal of opening up the field of gravitational-wave astronomy. Gravitational waves are best thought of as fluctuating, transversal strains in space–time. In an oversimplified analogy, they can be likened to sound waves, that is, as pressure waves of space–time travelling in vacuum at the speed of light. Like sound waves, gravitational waves come in the acoustic frequency band and, since gravitational-wave interferometers act essentially as microphones and lack directional specificity, the waves can be “heard” rather than “seen”, This means that a single observatory may detect a gravitational-wave burst but would have difficulty pinpointing its source. Just as two ears at opposite sides of the head are necessary to locate the origin of a sound, a network of several detectors at distant points around the Earth can triangulate the sources of gravitational waves in space. This requires a global network and is critical for pinpointing the location of the source in the sky so that other instruments, such as optical telescopes, can provide additional information about the source. In addition, signals as weak as gravitational waves require coincidence detection in several distant locations to confirm their validity by rejecting spurious events generated by local noise.

Before Virgo joined, the LSC already consisted of two major gravitational-wave observatories in the US – one in Livingston, Louisiana, and the other in Hanford, Washington – as well as the smaller European GEO600 observatory in Germany. The addition of the Virgo interferometer to this network has greatly reinforced its detection and pointing capabilities. The Livingston observatory hosts a single interferometer with a pair of 4 km arms. Hanford has two instruments: a 4 + 4 km interferometer like that at Livingston and a smaller 2 + 2 km one. GEO has a single 0.6 + 0.6 km interferometer, while Virgo operates a 3 + 3 km one. The introduction of Fabry–Perot cavities in the arms boosts the sensitivity of the three larger interferometers, extending the effective lengths of the arms to hundreds of kilometres. GEO600 increases its effective arm length to 1.2 km by using a folded beam.

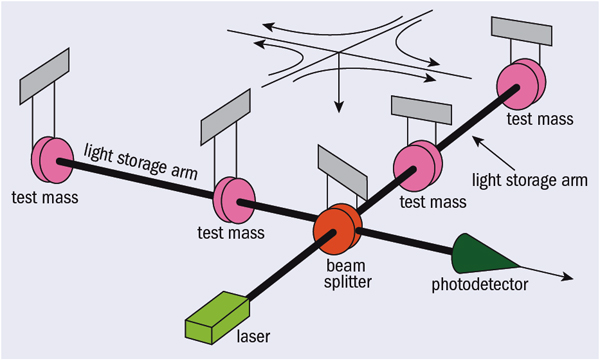

Image credit: INFN/EGO.

Japan has a somewhat smaller (0.3 + 0.3 km) interferometer, known as TAMA, located in Mitaka, near Tokyo. It is currently being refurbished with advanced seismic isolators and should soon join the growing gravitational-wave network. Japan is also considering the construction of the Large-scale Cryogenic Gravitational-Wave Telescope (LCGT). This would be a 3 + 3 km, underground interferometer with cryogenic mirrors, which would later become part of the global array of gravitational-wave interferometers. Australia is also developing technologies for gravitational-wave instruments and is planning to build an interferometer.

The effectiveness of gravitational-wave observatories is characterized both by their “reach” and by their duty cycle. The reach is conventionally defined as the maximum distance at which the inspiral signal of two neutron stars (each 1.4 solar masses) would be detectable with the available sensitivity. In gravitational-wave astronomy, improvements in sensitivity achieve more than they do in optical astronomy. Doubled sensitivity equals double reach, resulting in an eightfold increase in the observed cosmic volume and in the expected event rate. Similarly, because of the coincidence requirements between multiple interferometers, the duty cycle of a gravitational-wave observatory is more important than in a stand-alone optical instrument.

During the fifth science run, the two larger LIGO interferometers showed a detection range for the inspiral of two neutron stars of 15–16 Mpc, while the half-length interferometer had a reach of 6–7 Mpc. Virgo, with its partial commissioning, achieved a reach of 4.5 Mpc during the recent first joint run with LIGO. Virgo did not yet reach its design sensitivity in this run. However, its seismic isolation system helped it to achieve a superior seismic event immunity, resulting in longer “locks” (with a record of 95 hours) and an excellent observational duty factor. (The interferometer can only take data when it is “locked” – when all of the mirrors are controlled and held in place to a small fraction of a wavelength of light.) LIGO reached a duty cycle of 85–88% at the end of its fifth science run, while Virgo reached the same level on its first run.

The duty cycle of the triple coincidence of Virgo, LIGO–Hanford and LIGO–Livingston exceeded 58% (or 54% when including the smaller, second Hanford interferometer) and 40% in conjunction with GEO600. This was an amazing achievement given the tremendous technical finesse required to maintain all of these complex instruments in simultaneous operation.

The gold-plated gravitational-wave event would be the detection of a neutron star (NS) or black hole (BH) inspiral. However, even at the present design sensitivity, the Virgo–LIGO network has a relatively small chance of detecting such events. Currently, LIGO could expect a probability of a few per cent each year of ever detecting NS–NS inspirals, with perhaps a larger probability of detecting NS–BH and BH–BH inspirals, and an unknown probability of detecting supernova explosions (only if asymmetric and in nearby galaxies) and rotating neutron stars (only if a mass distribution asymmetry is present).

As scientists analyse the valuable data just acquired from the successful science run, the three main interferometers will now undergo a one- to two-year period of moderate enhancements and final tuning, and then resume operation for another year of joint data acquisition with greater sensitivity and an order of magnitude better odds of detection. At the end of that period, the interferometers will undergo a more drastic overhaul to boost their sensitivity by an order of magnitude with respect to the present value. A tenfold increase in sensitivity will result in a thousandfold increase of the listened-to cosmic volume, and correspondingly, up to a thousand times improvement in detection probability.

At that point (expected in 2015–16), the network will be sensitive to inspiral events within at least 200 Mpc and we can expect to detect and map several such events a year, based on our current understanding of populations of astrophysical objects. This will mark the beginning of gravitational-wave astronomy, a new window to explore the universe in conjunction with the established electromagnetic-wave observatories and the neutrino detectors.

Beyond this already ambitious programme, the gravitational-wave community has begun tracing a roadmap to design even more powerful observatories for the future. Interferometers based on the surface of the Earth can operate with high sensitivity only above 10 Hz, as they are limited by the seismically activated fluctuations of Earth’s Newtonian attraction. This limits detection to the ripples generated by relatively small objects (tens to hundreds of solar masses) and to “modest” distances (redshift Z = 1). Third-generation observatories built deep underground, far from the perturbations of the Earth’s surface, would be able to detect gravitational waves down to 1 Hz, and be sensitive enough to detect the lower-frequency signals coming from more massive objects, such as intermediate-mass black holes. Finally, space-based gravitational-wave detection interferometers such as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) are being designed to listen at an even lower frequency band. LISA would detect millihertz signals coming from the supermassive black holes lurking at the centre of galaxies. The aim is to launch the interferometer around 10 years from now, as a collaboration between ESA and NASA.

Although gravitational waves have not yet been detected, the gravitational-wave community is poised to prove Einstein right and wrong: right in his prediction that gravitational waves exist, wrong in his prediction that we will never be able to detect them.