The study of rare isotopes with proton and neutron compositions far outside the “valley of stability” provides critical tests of nuclear models. Several facilities around the world produce such isotopes by directing energetic beams of nuclei into solid targets. Now researchers are exploring ways to extend their investigations by collecting the rare isotopes and forming them into new reaccelerated beams.

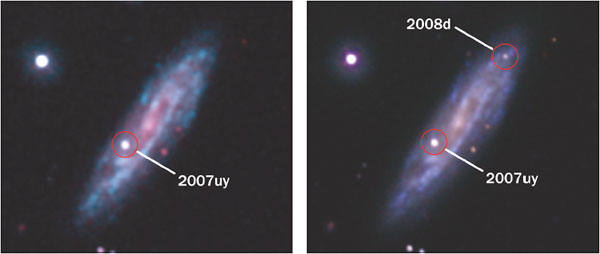

Image credit: NSCL.

There are two basic approaches to producing rare isotopes, which differ in the thickness of the target employed. Isotope separation on line (ISOL), developed some 40 years ago at CERN’s ISOLDE facility, uses a target that is thick enough for the nuclei to come to a stop within it. The isotopes can then be extracted, but this is a slow process – a problem for short-lived isotopes. In addition, each new element requires dedicated development work and some elements, such as refractory metals, are difficult or impossible to obtain.

Nonetheless, facilities such as ISOLDE, the Isotope Separator and Accelerator (ISAC) at TRIUMF and the Holifield Radioactive Beam Facility at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory have made important scientific advances using ISOL sources. They have extended the ISOL method further by accelerating the isotopes produced. At ISOLDE, the Radioactive Beam Experiment (REX) post-accelerator has pioneered the technique of increasing the charge state of low-energy, singly charged ions in an electron-beam ion source (EBIS) before reaccelerating them. TRIUMF recently stepped up its own production of radioactive beams with a superconducting linear accelerator to push the energies of rare isotopes above the Coulomb barrier.

The second approach to producing beams of rare isotopes is through projectile fragmentation, which separates the desired isotopes from the fragments that emerge when a fast heavy-ion beam impinges on a thin foil target. GANIL in France, RIKEN in Japan, GSI in Germany and the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory (NSCL) at Michigan State University (MSU) in the US all use this technique, which is less sensitive to the chemistry of the elements than ISOL. Projectile fragmentation makes it easier to produce and isolate rare isotopes, and it has made available thousands of different isotopes. The rate of generation tends to be smaller than for ISOL, however, and for experiments requiring slow beams the isotopes are not easy (or may even be impossible) to use because they emerge at a large fraction of the speed of light, with an energy in the region of 100 MeV per nucleon.

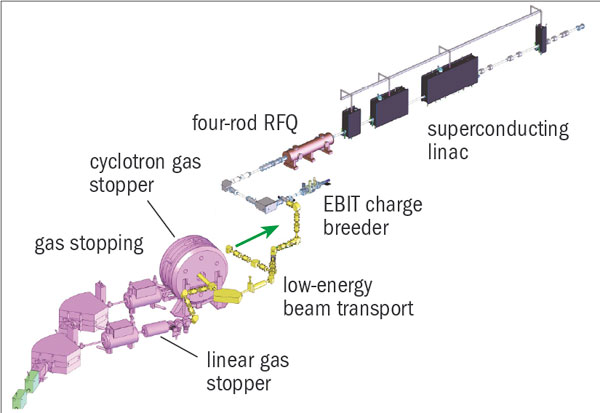

The obvious way to create low-energy beams is to slow down high-energy ones, but this severely degrades their quality. A better technical approach is to stop the beams, extract them and then reaccelerate them or use them at low energies. This is the path that MSU has opted for in upgrading its NSCL facility. To provide isotope beams with lower and more tightly distributed energies, it will combine new and established technology to stop the beams, increase the charge on the ions and then reaccelerate them. The resulting beams will enable users at NSCL to explore the excitations of rare isotopes – by either nucleon transfer or Coulomb excitation – to reveal their internal structure. In particular, their excited states provide stringent tests of nuclear models. “NSCL will be the first facility in the world to offer fast (about 50–150 MeV per nucleon), stopped and reaccelerated (up to 3 MeV per nucleon, for now) beams of rare isotopes, providing its users with an unusually broad arsenal of beams and experimental tools for their research,” says Konrad Gelbke, the director of NSCL.

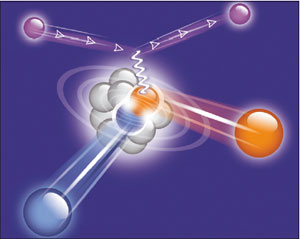

Image credit: NSCL.

The particles in the beams will have energies similar to those encountered in astrophysical environments, such as stellar explosions. “With these reaccelerated beams you can measure reactions at the actual astrophysical energies,” says MSU professor of nuclear astrophysics Hendrik Schatz. “That’s the big step.” Schatz and colleagues, including many among NSCL’s community of 700 researchers, hope to use the reaccelerated beams to explore reactions of unstable nuclei with protons in fixed targets or helium nuclei. These are the same reactions that occur in the astrophysical rapid-proton (rp) process and are believed to be important in X-ray bursts – the most abundant thermonuclear explosions in the universe. Future advances in the technology may help to probe the rapid-neutron (r) process reactions of neutron-rich nuclei, which occur in supernovae and are thought to give rise to many heavier chemical elements. The upgrade will help to test, refine and improve technological approaches that could be used for exploring rare isotopes at future facilities.

The approach taken towards reacceleration at NSCL involves slowing a high-energy beam by passing it through a solid degrader and bringing the ions to a stop, decreasing their initial spread of energy. The best-established stopping technology is the linear gas stopper – a tube of helium gas at pressures up to 1 bar. One important challenge, however, is to separate the desired isotopes from the many helium ions created during the stopping process. NSCL has already pioneered the use of these techniques to slow down isotopes produced by projectile fragmentation, allowing them to capture the isotopes in Penning traps for precision measurements.

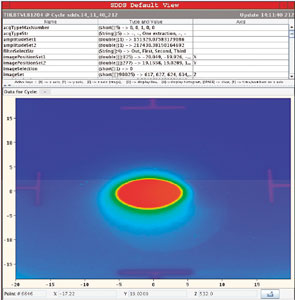

In parallel, Georg Bollen and colleagues at NSCL are developing a cyclotron stopper, which should be quite effective for lighter isotopes. Instead of travelling along a tube of helium several metres long, the ions tangentially enter a gas tube where a magnetic field diverts them into a circular orbit. As they travel multiple times around the circumference, they lose energy and spiral toward the axis, where they can be collected. The compact geometry allows this to be done effectively in the tens of milliseconds needed to use short-lived isotopes. The NSCL team plans to explore both an advanced version of linear gas stopping and cyclotron gas stopping in the reacceleration project to evaluate how these steps contribute to the overall system.

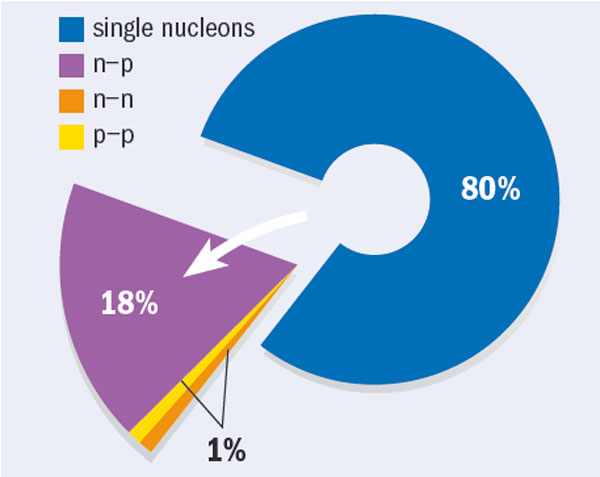

Another enabling technology used for reacceleration is the breeding of high charges on the ions to get the maximum energy from limited acceleration voltage. The “classic” approach first accelerates singly charged ions, then passes them through foils to strip off electrons before further accelerating the multiply charged ions. This method – used, for example, in ISAC at TRIUMF – is robust and established, but creates a variety of charge states. Electron-cyclotron resonance plasmas, which are used in Japan and elsewhere for charge breeding, also create multiple charge states. Since only a single state can be selected, both of these techniques have an inherently limited efficiency in using precious rare isotopes.

NSCL will use a different breeder to increase the charges – namely the electron-beam ion trap, pioneered (as the EBIS) at REX-ISOLDE. Here, ions are electrostatically attracted to an intense electron beam as well as ionized by it. One advantage is that, by targeting stable electronic shells and selectively extracting charge states from the trap, the system can produce isotopes with a single high-charge state. “You can make use of noble-gas configuration – you get a nice enhancement in a single charge state,” explains Bollen.

Once the isotopes have high charges, they are reaccelerated using a standard superconducting linear accelerator. The initial plans at NSCL call for relatively modest energies (around 3 MeV per nucleon) but more cavities can be added as needed to boost the energy. The system is designed for efficient processing of rare isotopes at each stage, as well as for the efficient transfer between successive stages.

The technologies developed for this upgrade will provide important technical experience for the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB), for which the US Department of Energy (DOE) has invited proposals. This machine would use a linear accelerator for the primary beam and provide higher initial isotope fluxes than the current cyclotron source at NSCL, which could make more experiments (including on the neutron-rich side) possible. Researchers at NSCL, who will explore how well the various components of the reacceleration project can scale to higher beam currents, have already laid the groundwork for FRIB. In autumn 2007, the laboratory published a detailed white paper describing a next-generation facility based on a superconducting 200 MeV, 400 kW heavy-ion driver with the possibility of experiments using fast, stopped and reaccelerated beams. These are all elements required for FRIB.

Karsten Riisager of CERN acknowledges that the NSCL upgrade will complement existing capabilities, noting that no single technical approach is superior. Although ISOL-based facilities like CERN’s REX-ISOLDE usually supply higher beam current, “for some of the exotic beams, such as short-lived isotopes, NSCL may have an advantage”, he says. Some elements are not available at all using ISOL techniques. He notes, however, that NSCL provides only nuclei lighter than about the mass of tin. “We [ISOLDE] are the only place right now where you have the very heavy nuclei reaccelerated.”

Bollen, who served as ISOLDE group leader in the late-1990s, and who plays a leading role at NSCL, is optimistic about the technology and science that the upgrade will enable. “We will produce reaccelerated beams which are not accessible at other facilities anywhere in the world now,” he says. Adds Gelbke: “History has taught us that new and unique tools often go hand in hand with new discoveries – and lead to further refinements based on the unique experience gained.”