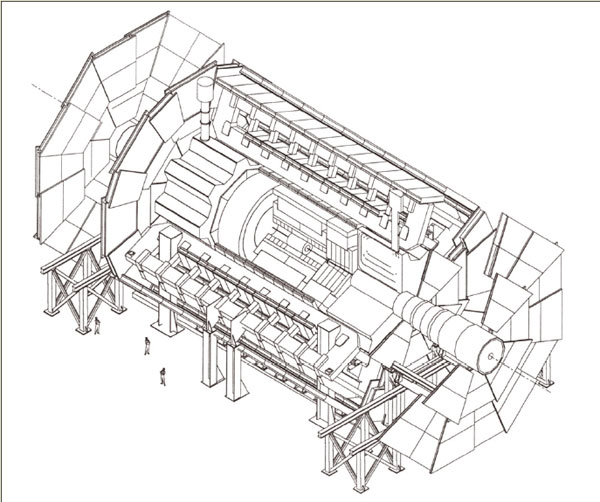

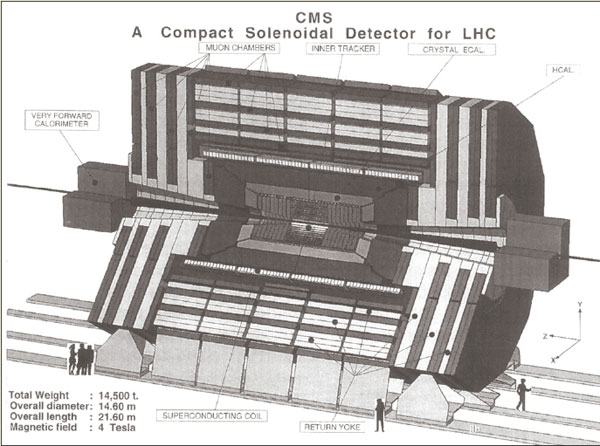

The milestone workshops on LHC experiments in Aachen in 1990 and at Evian in 1992 provided the first sketches of how LHC detectors might look. The concept of a compact general-purpose LHC experiment based on a solenoid to provide the magnetic field was first discussed at Aachen, and the formal expression of interest was aired at Evian. It was here that the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) name first became public.

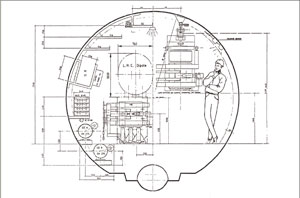

Optimizing first the muon-detection system is a natural starting point for a high-luminosity (interaction rate) proton–proton collider experiment. The compact CMS design called for a strong magnetic field, of some 4 T, using a superconducting solenoid, originally about 14 m long and 6 m bore. (By LHC standards, this warrants the adjective “compact”.)

The main design goals of CMS are: 1) a very good muon system providing many possibilities for momentum measurement; 2) the best possible electromagnetic calorimeter consistent with the above; 3) high-quality central tracking to achieve both the above; and 4) an affordable detector.

Overall, CMS aims to detect cleanly the diverse signatures of new physics by identifying and precisely measuring muons, electrons and photons over a large energy range at very high collision rates, while also exploiting the lower luminosity initial running. As well as proton–proton collisions, CMS will also be able to look at the muons emerging from LHC heavy-ion beam collisions.

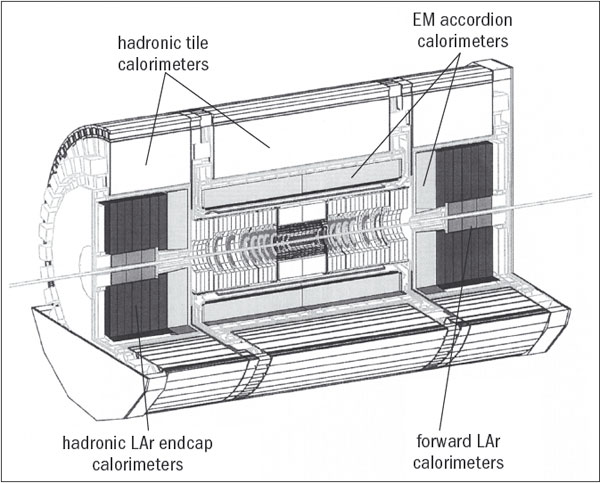

The Evian CMS conceptual design foresaw the full calorimetry inside the solenoid, with emphasis on precision electromagnetic calorimetry for picking up photons. (A light Higgs particle will probably be seen via its decay into photon pairs.) The muon system now foresaw four stations. Inner tracking would use silicon microstrips and microstrip gas chambers, with over 107 channels offering high track-finding efficiency. In the central CMS barrel, the tracking elements are mounted on spirals, providing space for cabling and cooling.

Following Evian, a letter of intent signed by 443 scientists from 62 institutes was presented to the then new LHC Experiments Committee. Two electromagnetic-calorimetry routes were proposed, a preferred one based on homogeneous media, and the other on a less expensive sampling solution using a lead/scintillator sandwich read out by wavelength-shifting fibres, named shashlik.

Due to limited resources in the collaboration at the time, the shashlik solution was adopted as baseline. However, R&D continued on cerium fluoride (CeF3) and two other candidate media, lead-tungstate crystals (PbWO4) and hafnium-fluoride glasses. The collaboration had doubled in size by the summer of 1994 and in September of that year lead tungstate was chosen after extensive beam tests of matrices of shashlik, cerium fluoride and tungstate towers. The radiation length of PbWO4 is only 0.9 cm and the required volume (approximately 12.5 m3) is only half that for CeF3, leading to a substantial reduction in cost. In addition, lead tungstate is a relatively easy crystal to grow from readily available raw materials and significant production capacity already exists.

Following the November 1993 decision to foreclose the SSC project, US physicists were looking for new possibilities and many knocked at the CMS door. A letter of intent submitted to the US Department of Energy in September 1994 covered a 270-strong US contingent in CMS, where the main responsibility would be for the endcap muon system and barrel hadronic calorimeter.

Meanwhile, interest continued to grow so that CMS now involves some 1250 scientists from 132 institutions in 28 countries. Some 600 scientists are from CERN member states, the remainder hail from further afield: some 300 from 37 institutes in the US, and 250 from research institutes in Russia and member states of the international Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna, near Moscow.

The choice of magnet was the starting point for the whole CMS design. Although the solenoid has been cut from 14 to 13 m in length, its radius (2.95 m) and magnetic field (4 T) remain unaltered. This long and high field solenoid removes the need for additional forward magnets for muon coverage, while accommodating easily the tracking and calorimetry.

The 12-sided structure, designed at CERN, is subdivided along the beam axis into five rings, each some 2.6 m long, with the central one supporting the inner superconducting coil. Endcaps complete the magnetic volume. The coil itself, designed at Saclay, is split into four sections, each 6.8 m in diameter, the maximum girth compatible with transport by road. The conductor is 40-strand niobium-titanium enclosed in an aluminium stabilizer. With 900 W of cooling power at 4.5 K and 3400 W at 60 K, cooldown will take 32 days.

In order to deal with high track multiplicities in the inner tracking cavity, detectors with small cell sizes are needed. Solid-state and gas-microstrip detectors provide the required granularity and precision. Two layers of pixel detectors have been added to improve the measurement of the track-impact parameter and secondary vertices. The silicon-pixel and microstrip detectors will be kept at 0° to slow down damage by irradiation. High track finding efficiencies are achieved for isolated high transverse-momentum tracks. It is also fairly high for such tracks in jets. All high transverse-momentum tracks produced in the central region are reconstructed with high-momentum precision (5 per mil), a direct consequence of the high magnetic field. The responsibility for the inner tracker extends to institutes in Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, India, Italy, Switzerland, the UK, the US and CERN.

Centrally produced muons are identified and measured in four muon stations inserted in the magnet-return yoke. The chambers are judiciously arranged to maximize the geometric acceptance. Each muon station consists of 12 planes of aluminium drift tubes designed to give a muon vector in space, with 100 μm precision in position and better than 1 mrad in direction.

The four muon stations also include resistive-plate chamber-triggering planes that identify the bunch crossing and enable a cut on the muon transverse momentum at the first trigger level. The endcap muon system also consists of four muon stations. Each station consists of six planes of Cathode Strip Chambers. The final muon stations come after a substantial amount of absorber so that only muons can reach them. The large bending power is the key to very good momentum resolution even in the so-called “stand alone” mode, especially at high transverse momenta. The muon-system team includes scientists from Austria, China, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland and Spain with large contingents from the US and Dubna member states.

As the coil radius is large enough to install essentially all the calorimetry inside, a high-precision electromagnetic calorimeter can be envisaged. The lead-tungstate (PbWO4) crystal calorimeter leads to a di-photon mass resolution twice as good as that anticipated from the shashlik. The electromagnetic calorimeter groups scientists with large experience of total absorption calorimeters from China, Dubna member states, France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, the UK, the US and CERN.

The hadron calorimeter, benefiting from US involvement, will use interleaved copper plates and plastic scintillator tiles read out by wavelength-shifting fibres. As well as the US, the CMS hadron calorimetry squad includes institutes from China, Hungary, India, Spain and Dubna member states.

For LHC’s design luminosity of 1034 cm–2 s–1, CMS will have to digest 20 highly complex collisions every 25 ns. This input rate of 109 interactions per second has to be reduced to just 100 for off-line analysis. This will be accomplished by a two-level trigger. The first-level trigger uses pipelined information from the muon detectors and the calorimeters to reach a decision after a fixed time period of 3 μs. The data from a maximum of 10s interactions per second, from the muon detectors and the calorimeters only, is forwarded to an online processor farm. This “virtual” Level 2 uses the full granularity to reject almost 90% of the events. The entire data from the remaining events is then passed to the farm for further processing. The trigger- and data-acquisition systems are the responsibility of a team from Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Poland, Dubna Member States, Spain, Switzerland, the UK, the US and CERN. Software and computing, for monitoring and control as well as data handling and analysis, will take on a new dimension at the LHC.

• June 1995 pp5–8 (abridged).

CMS changes to silicon track

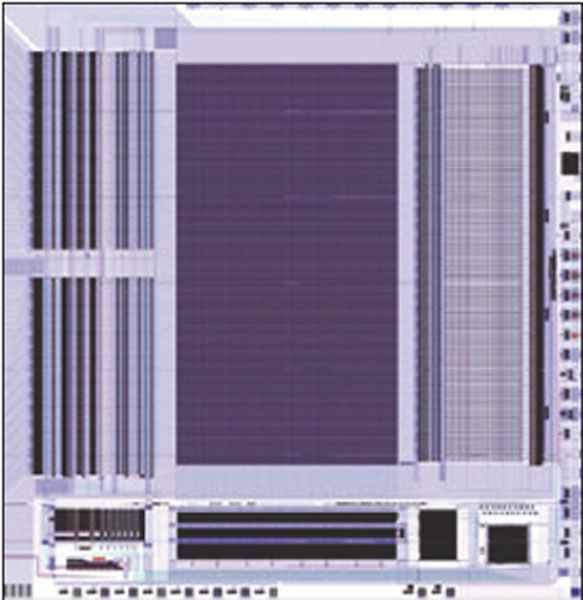

The collaboration for the CMS experiment will base its tracker entirely on silicon sensor technology using fine-feature-size electronics. The decision to go all-silicon follows unexpectedly rapid recent advances in read-out for microstrip detectors, in the fabrication of sensors on 6 inch diameter silicon wafers, and automated assembly techniques for an all-silicon detector. It is a significant departure from the CMS baseline-tracker proposal, which foresaw a central region of silicon devices surrounded by microstrip gas chambers (MSGCs).

In the mid-1990s, MSGCs seemed to offer an economical alternative to silicon. In early implementations, however, their performance was found to deteriorate significantly with increased exposure to ionizing particles. Nevertheless, solutions to these teething problems seemed to be available and CMS chose MSGCs as their baseline proposal – on the condition that certain milestones were reached. These were successfully achieved, but silicon-related technology was advancing in parallel, reducing the cost advantage that MSGCs offered.

A decisive factor in reducing the tracker’s price tag, by almost SFr6.5 million, was the development by CMS of a CMOS read-out chip using low-cost technology, originally aimed at increasing the compactness of computer chips. With a feature size of 0.25 μm compared with the 1 μm of conventional CMOS chips, the new APV25 chip is certainly compact. It is also extremely radiation-hard, with lower noise and power consumption than a conventional CMOS chip. The other decisive factor is that silicon detectors are already widely available from industry in large quantities and their price has been falling.

• May 2000 p5 (abridged).