The principal goal of the experimental programme at the LHC is to make the first direct exploration of a completely new region of energies and distances, to the tera-electron-volt scale and beyond. The main objectives include the search for the Higgs boson and whatever new physics may accompany it, such as supersymmetry or extra dimensions, and also – perhaps above all – to find something that the theorists have not predicted.

The Standard Model of particles and forces summarizes our present knowledge of particle physics. It extends and generalizes the quantum theory of electromagnetism to include the weak nuclear forces responsible for radioactivity in a single unified framework; it also provides an equally successful analogous theory of the strong nuclear forces.

The conceptual basis for the Standard Model was confirmed by the discovery at CERN of the predicted weak neutral-current form of radioactivity and, subsequently, of the quantum particles responsible for the weak and strong forces, at CERN and DESY respectively. Detailed calculations of the properties of these particles, confirmed in particular by experiments at the LEP collider, have since enabled us to establish the complete structure of the Standard Model; data taken at LEP agreed with the calculations at the per mille level.

These successes raise deeper problems, however. The Standard Model does not explain the origin of mass, nor why some particles are very heavy while others have no mass at all; it does not explain why there are so many different types of matter particles in the universe; and it does not offer a unified description of all the fundamental forces. Indeed, the deepest problem in fundamental physics may be how to extend the successes of quantum physics to the force of gravity. It is the search for solutions to these problems that define the current objectives of particle physics – and the programme for the LHC.

Higgs, hierarchy and extra dimensions

Understanding the origin of mass will unlock some of the basic mysteries of the universe: the mass of the electron determines the sizes of atoms, while radioactivity is weak because the W boson weighs as much as a medium-sized nucleus. Within the Standard Model the key to mass lies with an essential ingredient that has not yet been observed, the Higgs boson; without it the calculations would yield incomprehensible infinite results. The agreement of the data with the calculations implies not only that the Higgs boson (or something equivalent) must exist, but also suggests that its mass should be well within the reach of the LHC.

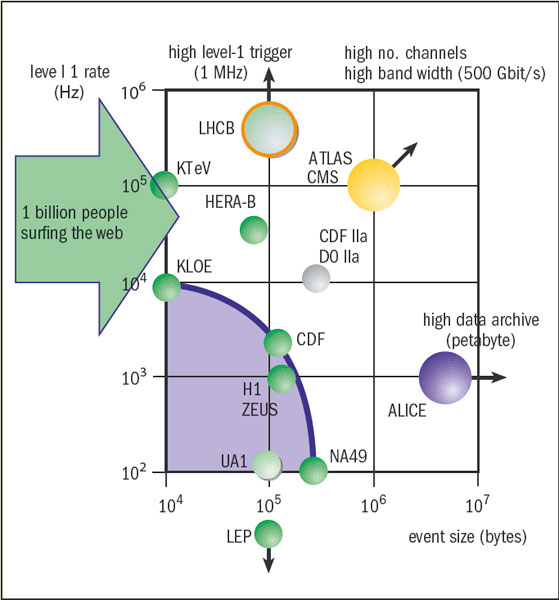

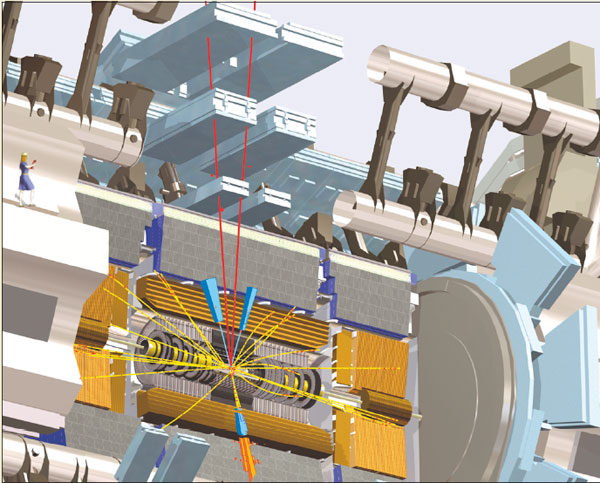

Experiments at LEP at one time found a hint for the existence of the Higgs boson, but these searches proved unsuccessful and told us only that it must weigh at least 114 GeV. At the LHC, the ATLAS and CMS experiments will be looking for the Higgs boson in several ways. The particle is predicted to be unstable, decaying for example to photons, bottom quarks, tau leptons, W or Z bosons (figure 1). It may well be necessary to combine several different decay modes to uncover a convincing signal, but the LHC experiments should be able to find the Higgs boson even if it weighs as much as 1 TeV.

While resolving the Higgs question will set the seal on the Standard Model, there are plenty of reasons to expect other, related new physics, within reach of experiments at the LHC. In particular, the elementary Higgs boson of the Standard Model seems unlikely to exist in isolation. Specifically, difficulties arise in calculating quantum corrections to the mass of the Higgs boson. Not only are these corrections infinite in the Standard Model, but, if the usual procedure is adopted of controlling them by cutting the theory off at some high energy or short distance, the net result depends on the square of the cut-off scale. This implies that, if the Standard Model is embedded in some more complete theory that kicks in at high energy, the mass of the Higgs boson would be very sensitive to the details of this high-energy theory. This would make it difficult to understand why the Higgs boson has a (relatively) low mass and, by extension, why the scale of the weak interactions is so much smaller than that of grand unification, say, or quantum gravity.

This is known as the “hierarchy problem”. One could try to resolve it simply by postulating that the underlying parameters of the theory are tuned very finely, so that the net value of the Higgs boson mass after adding in the quantum corrections is small, owing to some suitable cancellation. However, it would be more satisfactory either to abolish the extreme sensitivity to the quantum corrections, or to cancel them in some systematic manner.

One way to achieve this would be if the Higgs boson is composite and so has a finite size, which would cut the quantum corrections off at a relatively low energy scale. In this case, the LHC might uncover a cornucopia of other new composite particles with masses around this cut-off scale, near 1 TeV.

The alternative, more elegant, and in my opinion more plausible, solution is to cancel the quantum corrections systematically, which is where supersymmetry could come in. Supersymmetry would pair up fermions, such as the quarks and leptons, with bosons, such as the photon, gluon, W and Z, or even the Higgs boson itself. In a supersymmetric theory, the quantum corrections due to the pairs of virtual fermions and bosons cancel each other systematically, and a low-mass Higgs boson no longer appears unnatural. Indeed, supersymmetry predicts a mass for the Higgs boson probably below 130 GeV, in line with the global fit to precision electroweak data.

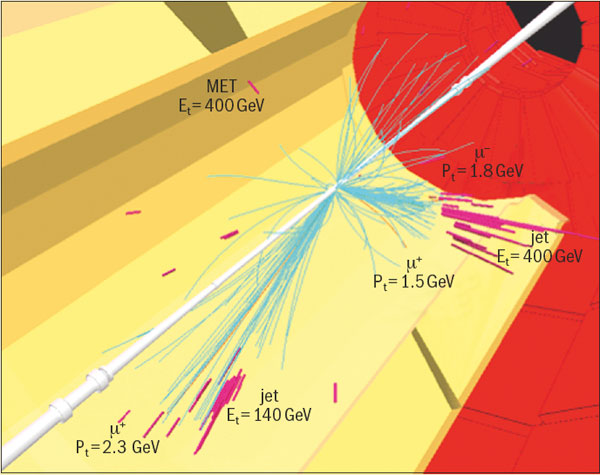

The fermions and bosons of the Standard Model, however, do not pair up with each other in a neat supersymmetric manner. The theory, therefore, requires that a supersymmetric partner, or sparticle, as yet unseen, accompanies each of the Standard Model particles. Thus, this scenario predicts a “scornucopia” of new particles that should weigh less than about 1 TeV and could be produced by the LHC (figure 3).

Another attraction of supersymmetry is that it facilitates the unification of the fundamental forces. Extrapolating the strengths of the strong, weak and electromagnetic interactions measured at low energies does not give a common value at any energy, in the absence of supersymmetry. However, there would be a common value, at an energy around 1016 GeV, in the presence of supersymmetry. Moreover, supersymmetry provides a natural candidate, in the form of the lightest supersymmetric particle (LSP), for the cold dark matter required by astrophysicists and cosmologists to explain the amount of matter in the universe and the formation of structures within it, such as galaxies. In this case, the LSP should have neither strong nor electromagnetic interactions, since otherwise it would bind to conventional matter and be detectable. Data from LEP and direct searches have already excluded sneutrinos as LSPs. Nowadays, the “scandidates” most considered are the lightest neutralino and (to a lesser extent) the gravitino.

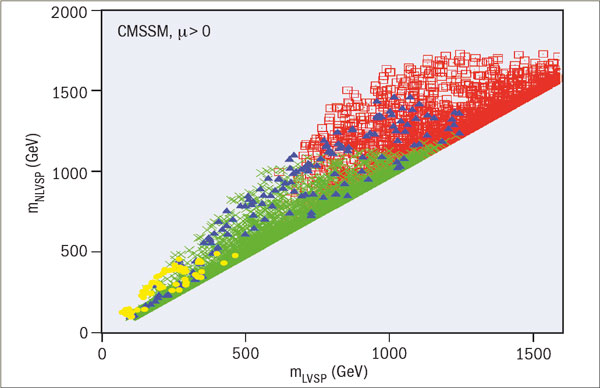

Assuming that the LSP is the lightest neutralino, the parameter space of the constrained minimal supersymmetric extension of the Standard Model (CMSSM) is restricted by the need to avoid the stau being the LSP, by the measurements of b → sγ decay that agree with the Standard Model, by the range of cold dark-matter density allowed by astrophysical observations, and by the measurement of the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon (gμ–2). These requirements are consistent with relatively large masses for the lightest and next-to-lightest visible supersymmetric particles, as figure 4 indicates. The figure also shows that the LHC can detect most of the models that provide cosmological dark matter (though this is not guaranteed), whereas the astrophysical dark matter itself may be detectable directly for only a smaller fraction of models.

Within the overall range allowed by the experimental constraints, are there any hints at what the supersymmetric mass scale might be? The high precision measurements of mW tend to favour a relatively small mass scale for sparticles. On the other hand, the rate for b → sγ shows no evidence for light sparticles, and the experimental upper limit on Bs → μ+μ– begins to exclude very small masses. The strongest indication for new low-energy physics, for which supersymmetry is just one possibility, is offered by gμ–2. Putting this together with the other precision observables gives a preference for light sparticles.

Other proposals for additional new physics postulate the existence of new dimensions of space, which might also help to deal with the hierarchy problem. Clearly, space is three-dimensional on the distance scales that we know so far, but the suggestion is that there might be additional dimensions curled up so small as to be invisible. This idea, which dates back to the work of Theodor Kaluza and Oskar Klein in the 1920s, has gained currency in recent years with the realization that string theory predicts the existence of extra dimensions and that some of these might be large enough to have consequences observable at the LHC. One possibility that has emerged is that gravity might become strong when these extra dimensions appear, possibly at energies close to 1 TeV. In this case, some variants of string theory predict that microscopic black holes might be produced in the LHC collisions. These would decay rapidly via Hawking radiation, but measurements of this radiation would offer a unique window onto the mysteries of quantum gravity.

If the extra dimensions are curled up on a sufficiently large scale, ATLAS and CMS might be able to see Kaluza–Klein excitations of Standard Model particles, or even the graviton. Indeed, the spectroscopy of some extra-dimensional theories might be as rich as that of supersymmetry while, in some theories, the lightest Kaluza–Klein particle might be stable, rather like the LSP in supersymmetric models.

Back to the beginning

By colliding particles at very high energies we can recreate the conditions that existed a fraction of a second after the Big Bang, which allows us to probe the origins of matter. Experiments at LEP revealed that there are just three “families” of elementary particles: one that makes up normal stable matter, and two heavier unstable families that were revealed in cosmic rays and accelerator experiments. The Standard Model does not explain why there are three and only three families, but it may be that their existence in the early universe was necessary for matter to emerge from the Big Bang, with little or no antimatter.

Andrei Sakharov was the first to point out that particle physics could explain the origin of matter in the universe by the fact that matter and antimatter have slightly different properties, as discovered in the decays of K and B mesons, which contain strange and bottom quarks, members of the heavier families. These differences are manifest in the phenomenon of CP violation. Present data are in good agreement with the amount of CP violation allowed by the Standard Model, but this would be insufficient to generate the matter seen in the universe.

The Standard Model accounts for CP violation within the context of the Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa (CKM) matrix, which links the interactions between quarks of different type (or flavour). Experiments at the B-factories at KEK and SLAC have established that the CKM mechanism is dominant, so the question is no longer whether this is “right”. The task is rather to look for additional sources of CP violation that must surely exist, to create the cosmological matter–antimatter asymmetry via baryogenesis in the early universe. If the LHC does observe any new physics, such as the Higgs boson and/or supersymmetry, it will become urgent to understand its flavour and CP properties.

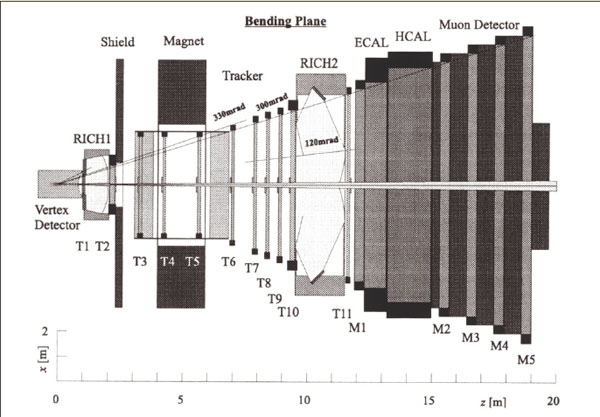

The LHCb experiment will be dedicated to probing the differences between matter and antimatter, notably looking for discrepancies with the Standard Model. The experiment has unique capabilities for probing the decays of mesons containing both bottom and strange quarks. It will be able to measure subtle CP-violating effects in Bs decays, and will also improve measurements of all the angles of the unitarity triangle, which expresses the amount of CP violation in the Standard Model. The LHC will also provide high sensitivity to rare B decays, to which the ATLAS and CMS experiments will contribute, in particular, and which may open another window on CP violation beyond the CKM model.

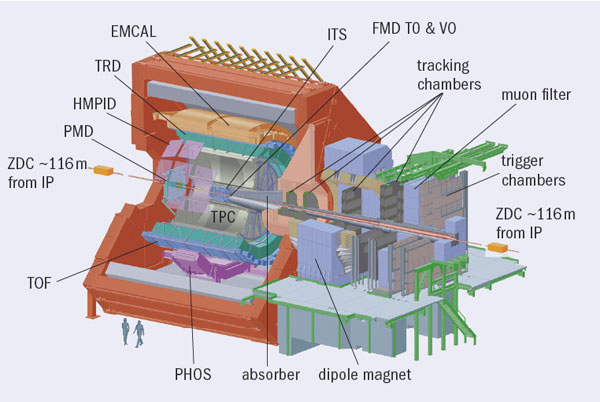

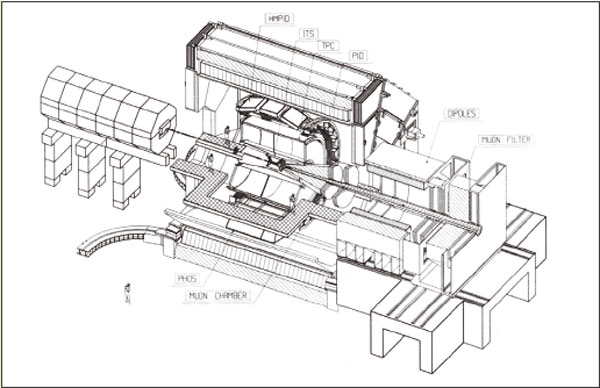

In addition to the studies of proton–proton collisions, heavy-ion collisions at the LHC will provide a window onto the state of matter that would have existed in the early universe at times before quarks and gluons “condensed” into hadrons, and ultimately the protons and neutrons of the primordial elements. When heavy ions collide at high energies they form for an instant a “fireball” of hot, dense matter. Studies, in particular by the ALICE experiment, may resolve some of the puzzles posed by the data already obtained at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven. These data indicate that there is very rapid thermalization in the collisions, after which a fluid with very low viscosity and large transport coefficients seems to be produced. One of the surprises is that the medium produced at RHIC seems to be strongly interacting . The final state exhibits jet quenching and the semblance of cones of energy deposition akin to Machian shock waves or Cherenkov radiation patterns, indicative of very fast particles moving through a medium faster than sound or light.

Experiments at the LHC will enter a new range of temperatures and pressures, thought to be far into the quark–gluon plasma regime, which should test the various ideas developed to explain results from RHIC. The experiments will probably not see a real phase transition between the hadronic and quark–gluon descriptions; it is more likely to be a cross-over that may not have a distinctive experimental signature at high energies. However, it may well be possible to see quark–gluon matter in its weakly interacting high temperature phase. The larger kinematic range should also enable ideas about jet quenching and radiation cones to be tested.

First expectations

The first step for the experimenters will be to understand the minimum-bias events and compare measurements of jets with the predictions of QCD. The next Standard Model processes to be measured and understood will be those producing the W- and Z-vector bosons, followed by top-quark physics. Each of these steps will allow the experimental teams to understand and calibrate their detectors, and only after these steps will the search for the Higgs boson start in earnest. The Higgs will not jump out in the same way as did the W and Z bosons, or even the top quark, and the search for it will demand an excellent understanding of the detectors. Around the time that Higgs searches get underway, the first searches for supersymmetry or other new physics beyond the Standard Model will also start.

In practice, the teams will look for generic signatures of new physics that could be due to several different scenarios. For example, missing-energy events could be due to supersymmetry, extra dimensions, black holes or the radiation of gravitons into extra dimensions. The challenge will then be to distinguish between the different scenarios. For example, in the case of distinguishing between supersymmetry and universal extra dimensions, the spectra of higher excitations would be different in the two scenarios, the different spins of particles in cascade decays would yield distinctive spin correlations, and the spectra and asymmetries of, for instance, dileptons, would be distinguishable.

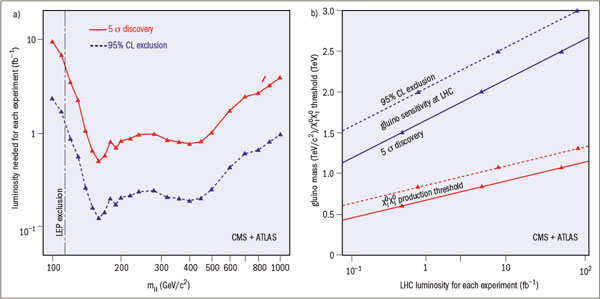

What is the discovery potential of this initial period of LHC running? Figure 5a shows that a Standard Model Higgs boson could be discovered with 5 σ significance with 5 fb–1 of integrated and well-understood luminosity, whereas 1 fb–1 would already suffice to exclude a Standard Model Higgs boson at the 95% confidence level over a large range of possible masses. However, as mentioned above, this Higgs signal would receive contributions from many different decay signatures, so the search for the Higgs boson will require researchers to understand the detectors very well to find each of these signatures with good efficiency and low background. Therefore, announcement of the Higgs discovery may not come the day after the accelerator produces the required integrated luminosity!

Paradoxically, some new physics scenarios such as supersymmetry may be easier to spot, if their mass scale is not too high. For example, figure 5b shows that 0.1 fb–1 of luminosity should be enough to detect the gluino at the 5 σ level if its mass is less than 1.2 TeV, and to exclude its existence below 1.5 TeV at the 95% confidence level. This amount of integrated luminosity could be gathered with an ideal month’s running at 1% of the design instantaneous luminosity.

We do not know which, if any, of the theories that I have mentioned nature has chosen, but one thing is sure: once the LHC starts delivering data, our hazy view of this new energy scale will begin to clear dramatically.

Based on the concluding talk at Physics at the LHC, Cracow, 3–8 July 2006 (http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-ph/0611237).