Georges Charpak, who died on 29 September, worked at CERN for most of his scientific career (CERN Courier November 2010 p6). It was there that he invented and developed the multiwire proportional chamber (MWPC), which led not only to a host of related detector techniques and applications, but also to the ultimate recognition of his contributions – the award of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1992.

Born in eastern Poland, Georges moved to Paris with his family in 1932 when he was seven. As a teenager he became active in the French resistance to fight against Nazi occupiers and was imprisoned by the French government in 1943, before being transferred to the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau in 1944. He survived because the guards did not realize that their political prisoner was Jewish. After the war he became a French citizen and in 1954 he received his doctorate in nuclear physics from the Collège de France in Paris, where he studied in the laboratory of Nobel laureate Frédéric Joliot-Curie. He devoted his early career to nuclear physics before making the transition to high-energy particle physics.

Pioneering times

Georges arrived at CERN in 1959, his first contributions being to the team that in 1961 precisely measured the anomalous magnetic-moment of the muon, predicted by QED (CERN Courier December 2005 p12). Testing this prediction to high accuracy is of paramount importance in particle physics because a small deviation from the theoretical value would imply new physics beyond the Standard Model. The pioneering experiment at CERN inspired many physicists in a line of research that continues to this day.

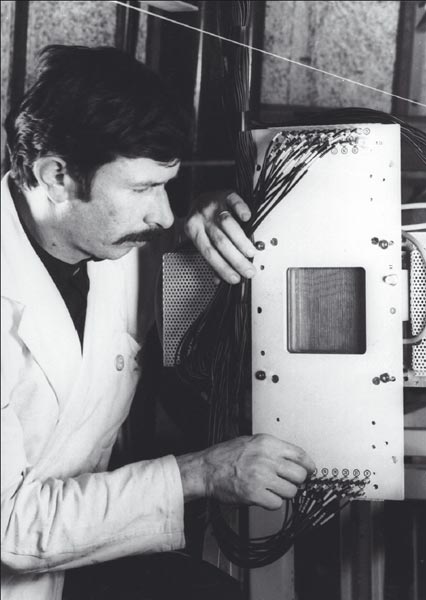

Only a few years later, in 1967–1968, he developed the MWPC, a gas-filled box with a large number of parallel detector wires, each connected to individual amplifiers. Unlike earlier detectors – such as the bubble chamber, which records a few photographs per second – the multiwire chamber could record up to a million tracks a second when linked to a computer. This new technology came at just the right moment as the computer era began to blossom and proper data-acquisition electronics were under intensive development.

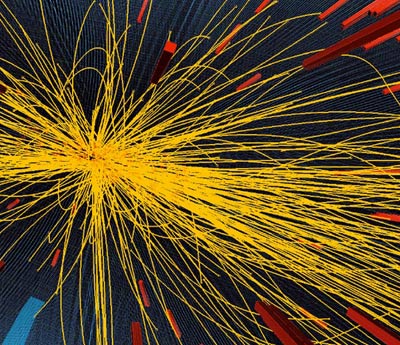

With the new detector, particle physics entered a new era. The speed and precision of the multiwire chamber and its offspring – the drift chamber and the time-projection chamber – revolutionized the field. Particle physicists must often sort through many millions of tracks to find one or two examples of the particles they seek, so they need fast detectors. The invention of the MWPC opened the way to operate experiments at much higher particle-collision rates and to test theories predicting the production of rare events and new massive particles. The discoveries of the W and Z bosons at CERN, the charm quark at SLAC and Brookhaven and the top quark at Fermilab would not have been possible without this type of detector, and current research in high-energy physics continues to depend on these devices.

It was an experimental technique that many others had attempted without much success, but the previous experience Georges had with similar detectors was a key to his achievement. Working with a cylindrical counter in the Collège de France in 1948, he had realized that signals were produced not by the drifting electrons released by the passage of an ionizing particle but rather by the movement of positive ions, which induce pulses of opposite polarity on the anode-sense wire. The MWPC amplifies the few ionization electrons through electron multiplication near the anode wires. The resulting avalanche produces a signal that can be timed, leading to a variety of high-precision spatial measurement systems. As Georges and his collaborators discovered, the pulses induced in orthogonal cathode strips in a MWPC permit a bi-dimensional read-out. Moreover, determination of the charge centroid provides a better accuracy along the cathode wires (better than 100 μm) than in the other direction, where the accuracy is limited by the spacing of the anode wires. This type of read-out has been used by many experiments and is still in use today at the LHC.

The pitch of the wires limits spatial resolution in the MWPC and the coverage of large areas requires many wires and, therefore, many channels of amplification and read-out. However, Georges and his co-workers found that delayed signals were seen in the MWPC and that the measurement of the time of these signals – the drift time – could provide high-accuracy spatial information. This forms the basis of the operation of the drift chamber, where the wires are much more widely spaced. Drift chambers have been developed by groups worldwide and are used in many experiments because of their economical read-out, high accuracy and the possibility to build detectors with large areas.

The combination of drift-time information with charge-centroid read-out offered the possibility of 3D read-out from a single chamber and in 1974 David Nygren at Berkeley proposed a new evolution of the drift chamber, the time-projection chamber (CERN Courier January/February 2004 p40). This has since been widely used by many experiments, in particular ALEPH and DELPHI at CERN’s Large Electron–Positron collider and now ALICE at the LHC.

In 1970 Fabio Sauli joined the group at CERN and played an important role in the subsequent developments of the multiwire chamber and the drift chamber. Among these was another promising concept, the multistep avalanche chamber. This was developed in the period 1979–1989 with the aim of reaching even higher counting rates. The basic idea was to split the amplification into two stages and overcome space-charge effects that otherwise counteracted the gain. Here, other distinguished physicists participated in the experimental effort, including Amos Breskin, Stan Majewski, Wotjek Dominic and Vladimir Peskov.

These detectors were subsequently developed further and adapted for detecting UV light to tackle new applications, ranging from fundamental research to medicine, biology and industry. One approach is to use a multistep parallel-plate avalanche chamber coupled to an image intensifier and a CCD to read the UV light emitted during the avalanche. In comparison with photographic emulsions, there is a significant gain in time for data acquisition, with the added advantages of linearity, wider dynamic range in the intensity measurement and a greatly improved signal-to-noise ratio. In collaboration with Tom Ypsilantis and his group, a particular effort was devoted to improving the ring-imaging Cherenkov (RICH) counter, which is used to identify elementary particles. From these investigations, new solid and gas UV photocathodes have been invented and developed.

Georges spent time and effort to push the application of these detectors in medical radiology, where the trend is for digital read-out to replace photographic film so as to improve sensitivity and spatial resolution. The multistep avalanche chambers found important applications in β-radiography, which is employed in medical and biological investigations to form “images” of human or animal tissues labelled with β-emitting radionuclides. In 1989 Georges founded a new company, Biospace Instruments, aimed at using this technology for biomedical applications as well as a high-pressure xenon multiwire chamber for low-dose radiography.

In the 1980s Georges and I began a close collaboration at CERN, developing new detector concepts adapted to solve specific problems in particle physics, including a high-energy gamma telescope with good energy resolution. In 1990 we began working with Leon Lederman on a new device – the “optical trigger” – which was to select particles containing the b quark in real time in high-intensity proton collisions. These particles fly a short distance before decaying and this serves to differentiate the decay products from other particles produced in the target. In a suitably positioned, thin crystal cell, internal reflection enhances the Cherenkov light produced by the decay products – while that from other relativistic particles passes straight through. This provides a way to tag the b-quark particles and enrich the collected sample with good events.

In 1991 we proposed the Hadron Blind Detector, which was then developed by an international collaboration. In this concept, most of the particles produced in proton collisions, which are hadrons, are not seen by the detector, while electrons and high-momentum muons are reconstructed efficiently. This selection criterion filters out unwanted events. The concept was demonstrated in October 1992 at CERN, just before the announcement of the Nobel prize, at a time when Georges and other team members were conducting experiments at night. In these investigations we used a gaseous parallel-plate detector and while optimizing it we demonstrated experimentally the advantage of a narrow amplification gap. This triggered the idea of building a device with an even narrower amplification gap and from that a new detector concept was born: the Micro-Mesh gaseous structure or MicroMegas, which our group at Saclay has developed since 1995. Georges used to say that this detector and some other new concepts belonging to the family of micropattern gaseous detectors (MPGDs) will revolutionize nuclear and particle physics just as his detector did.

Georges spent many weekends and summer holidays at his house in Cargèse, a village established by Greeks at the end of the 18th century in Corsica. His house was located two steps from the Institut d’Etudes Scientifiques de Cargèse. Developed by the physicist Maurice Lévy in the 1960s, the institute became an important summer school for theoretical physics, gathering together some distinguished physicists and many of those involved in the Standard Model, which was under intense development at that time. Georges used to join these lectures during summer and always welcomed the participants at his house nearby for a sip of wine. He invited many physicists to his house to discuss new ideas in physics as well as many other subjects. Among these visitors was Alvaro De Rújula, who with Georges, Sheldon Glashow and Robert Wilson proposed the use of neutrinos produced by a multi-tera-electron-volt proton synchrotron as a tool for geological research: at these energies, the neutrinos are suitable for “tomography” of the Earth because they have a range comparable to its diameter.

A concern for people

Given his experiences during the Second World War as a political prisoner it is perhaps not surprising that later in life Georges became a highly motivated humanitarian campaigner. In particular, he was a founder member of the Yuri Orlov committee, the human-rights group that was set up by a group of accelerator and particle physicists at CERN in 1980. Orlov, a Soviet physicist who had been imprisoned for his support of human rights, soon became a cause célèbre in the western scientific world. Shortly afterwards the committee broadened its scope to support Anatoly Shcharansky and Andrei Sakharov – also in the Soviet Union – and many individuals elsewhere from the worlds of science, mathematics and technology who, for political or ideological reasons, were being persecuted or imprisoned by authoritarian régimes of differing political colours. One of Georges’ many public actions in this context was at the press conference organized by the Yuri Orlov committee at the United Nations in Geneva in October 1980. Already an eminent figure in science at that time, and well respected for his complete freedom from ideological bias, he was able to contribute much to the influence of this and similar events. The combined efforts of such groups and individual activists eventually bore fruit in the form of favourable outcomes in these three particular cases as well as in others worldwide.

In the mid-1990s Georges returned to Paris and a new life with highly diversified activities began for him. Keen to popularize science, he became widely known to the general public through several books that made physics accessible to as wide an audience as possible. Together with Richard Garwin he wrote Megawatts and Megatons: A Turning Point in the Nuclear Age in which they evaluate the benefits of nuclear energy and show how it can provide an assured, economically feasible and environmentally responsible supply of energy that avoids the hazards of weapon proliferation. They make a strong statement in favour of arms control and outline specific strategies for achieving this goal worldwide. In 2004, with Henri Broch, he wrote Devenez Sorciers, Devenez Savants, later translated into English, which derided pseudoscience, astrology and other misconceptions (CERN Courier March 2005 p48).

Education was also of great importance to Georges. He created La Main à la P√¢te, an association to introduce hands-on science education in primary schools in France, an idea that had been first initiated in Chicago by his friend Leon Lederman. From 1996, with the support of the French Academy of Sciences and some of his colleagues, Georges propagated the new idea of teaching science in primary schools. The prestigious Ecole Nationale Superieur des Mines (ENSM) at Saint Etienne created a laboratory in his honour and established the “puRkwa Prize” to reward pedagogical initiatives that help children to acquire the scientific spirit.

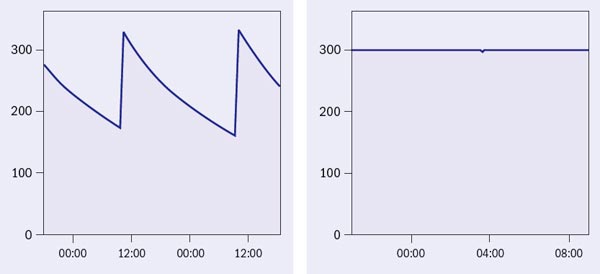

Since returning to Paris, part of his scientific activity was connected to the work in my laboratory at Saclay, which he used to visit several times a year. We kept an old oscilloscope especially for him, as he disliked the new digital devices. He co-signed many publications related to our research. One example in 1996 was the new development by CERN and Saclay of a promising way of fabricating the MicroMegas detector, referred to as “bulk” technology, which is now widely used by many experiments and allows the fabrication of large and cost-effective detectors (CERN Courier December 2009 p23). Every two years, since 2002, we have organized a conference in Paris on Large TPCs for Low-Energy Detection. The purpose of the meeting is an extensive discussion of present and future projects using a large time-projection chamber (TPC) for low-energy and low-background detection of rare events (low-energy neutrinos, double beta decay, dark matter, solar axions etc.). Georges actively participated in the conference, giving introductory talks that pointed out links between science, education and technology.

Image credit: I Giomataris.

Georges was active until the end. He recently published, together with François Vannucci, a new book, which can be considered as his testament, celebrating the physics that he loved. I met him at his home a day before his death and was impressed by the clarity of his mind. He was excited to hear of the new progress in physics and in detector developments conducted by my group. He was himself thinking about a novel radon detector, believing that its industrial success would allow him “to buy new shoes”, a phrase he used the day of the award of the Nobel prize 18 years ago.

Georges liked music and especially classic songs. He often invited musicians to his home in Paris and enjoyed the company of artists from the opera and friends at a typical Parisian bistro where they would sing around a piano player. For his last resting place, as he had wished, several musicians played classical music during the ceremony. I will keep in my memory a kind man, a humanist, who was enthusiastic, optimistic and always open to new ideas. I have the feeling, as many other colleagues do, that our second “father” has passed away.

I would like to thank Fabio Sauli, John Eades and Peter Schmid for their help in the preparation of this tribute.