The LHC’s Long Shutdown 1 (LS1) is an opportunity that the ATLAS collaboration could not miss to improve the performance of its huge and complex detector. Planning began almost three years ago to be ready for the break and to produce a precise schedule for the multitude of activities that are needed at Point 1 – where ATLAS is located on the LHC. Now, a year after the famous announcement of the discovery of a “Higgs-like boson” on 4 July 2012 and only six months after the start of the shutdown, more than 800 different tasks have been already accomplished in more than 250 work packages. But what is ATLAS doing and why this hectic schedule? The list of activities is long, so only a few examples will be highlighted here.

The inner detector

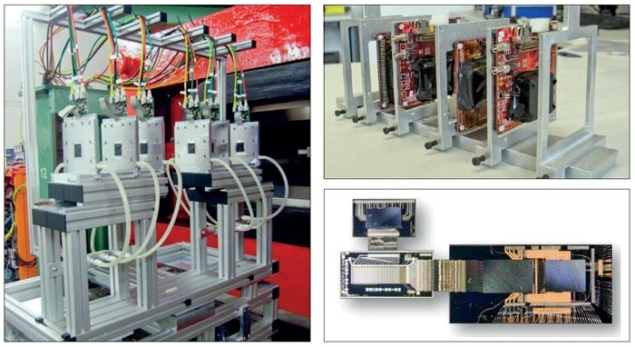

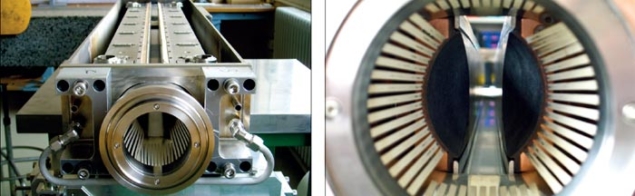

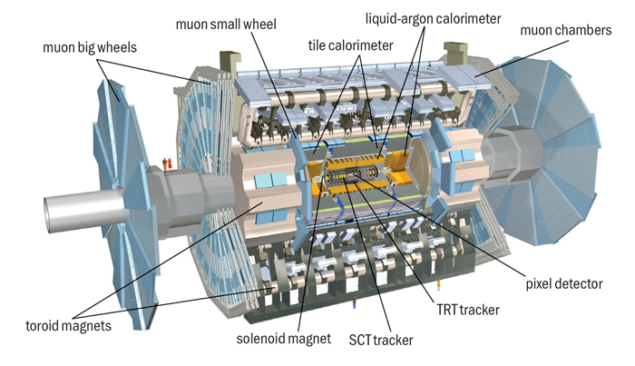

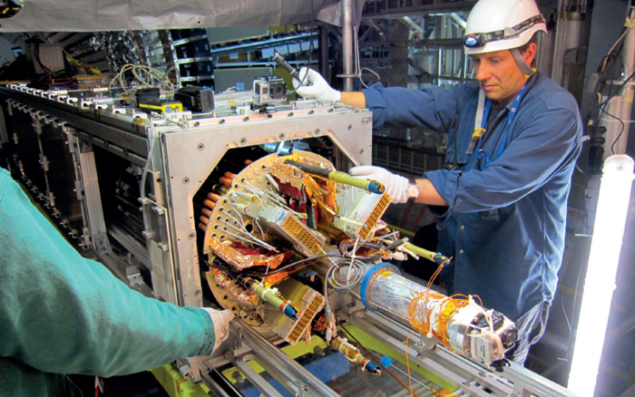

One of the biggest interventions concerns the insertion of a fourth and innermost layer of the pixel detector – the IBL. The ATLAS pixel detector is the largest pixel-based system at the LHC. With about 80 million pixels, until now it has covered a radius from 12 cm down to 5 cm from the interaction point. At its conception, the collaboration already thought that it could be updated after a few years of operation. An additional layer at a radius of about 3 cm would allow for performance consolidation, in view of the effects of radiation damage to the original innermost layer at 5 cm (the b-layer). The decision to turn this idea into reality was taken in 2008, with the aim of installation around 2016. However, fast progress in preparing the detector and moving the long shutdown to the end of 2012 boosted the idea and the installation goal was moved forward by two years.

Image credit: B Di Girolamo.

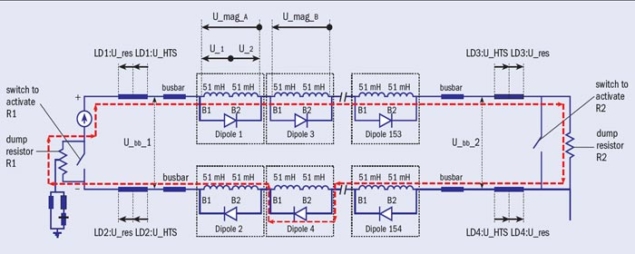

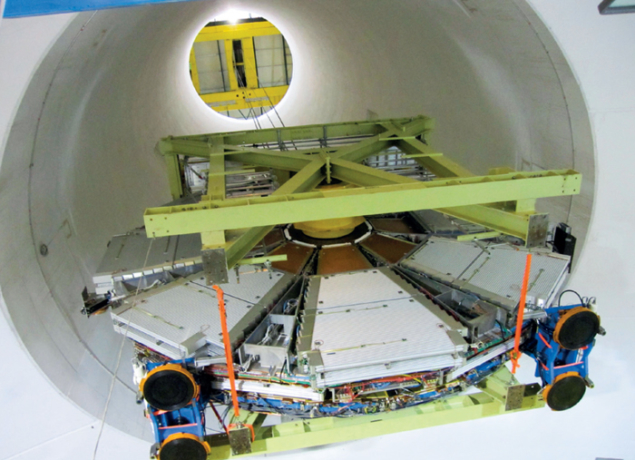

To make life more challenging, the collaboration decided to build the IBL using not only well established planar sensor technology but also novel 3D sensors. The resulting highly innovative detector is a tiny cylinder that is about 3 cm in radius and about 70 cm long but it will provide the ATLAS experiment with another 12 million detection channels. Despite its small dimensions, the entire assembly – including the necessary services – will need an installation tool that is nearly 10 m long. This has led to the so-called “big opening” of the ATLAS detector and the need to lift one of the small muon wheels to the surface.

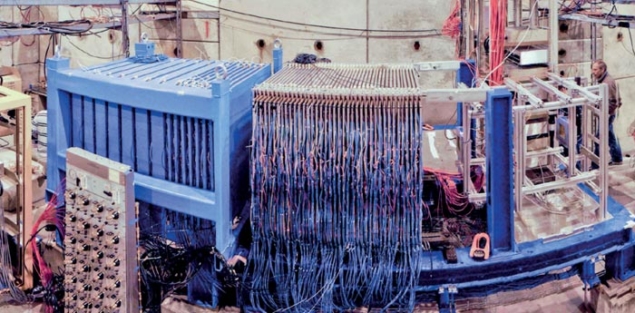

The “big opening” of ATLAS is a special configuration where at one end of the detector one of the big muon wheels is moved as far as possible towards the wall of the cavern, the 400-tonne endcap toroid is moved laterally towards the surrounding path structure, the small muon wheel is moved as far as the already opened big wheel and then the endcap calorimeter is moved out by about 3 m. But that is not the end of the story. To make more space, the small muon wheel must be lifted to the surface to allow the endcap calorimeter to be moved further out against the big wheels.

In 2011, the ATLAS pixel community decided to prepare new services for the detector – code-named nSQP

This opening up – already foreseen for the installation of the IBL – became more worthwhile when the collaboration decided to use LS1 to repair the pixel detector. During the past three years of operation, the number of pixel modules that have stopped being operational has risen continuously from the original 10–15 up to 88 modules, at a worryingly increasing rate. Back in 2010, the first concerns triggered a closer look at the module failures and it was clear that in most of the cases the modules were in a good state but that something in the services had failed. This first glance was then augmented by substantial statistics after up to 88 modules had failed by mid-2012.

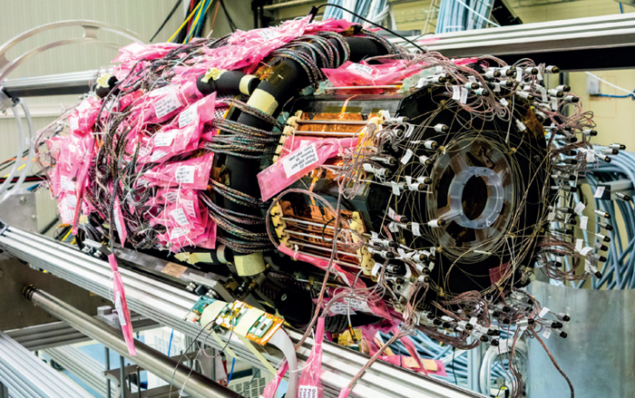

In 2011, the ATLAS pixel community decided to prepare new services for the detector – code-named nSQP for “new service quarter panels”. In January 2013, the collaboration decided to deploy the nSQP not only to fix the failures of the pixel modules and to enhance the future read-out capabilities for two of the three layers but also to ease the task of inserting the IBL into the pixel detector. This decision implied having to extract the pixel detector and take it to the clean-room building on the surface at Point 1 to execute the necessary work. The “big opening” therefore became mandatory.

Image credit: B Di Girolamo.

The extraction of the pixel detector was an extremely delicate operation but it was performed perfectly and a week in advance of the schedule. Work on both the original pixels and the IBL is now in full swing and preparations are under way to insert the enriched four-layer pixel detector back into ATLAS. The pixel detector will then contain 92 million channels – some 90% of the total number of channels in ATLAS.

But that is not the end of the story for the ATLAS inner detector. Gas leaks appeared last year during operation of the transition radiation tracker (TRT) detector. Profiting from the opening of the inner detector plates to access the pixel detector, a dedicated intervention was performed to cure as many leaks as possible using techniques that are usually deployed in surgery.

Further improvements

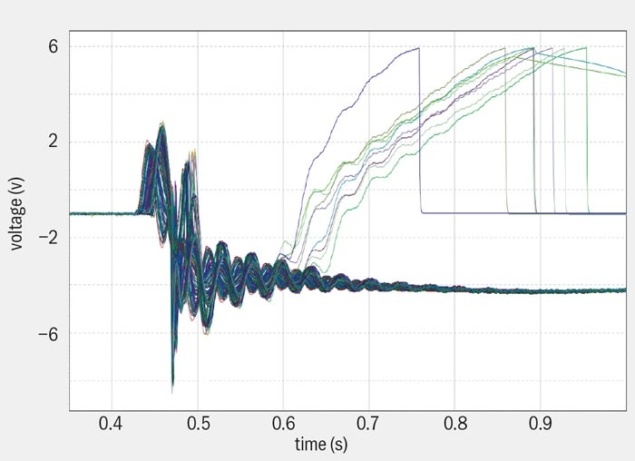

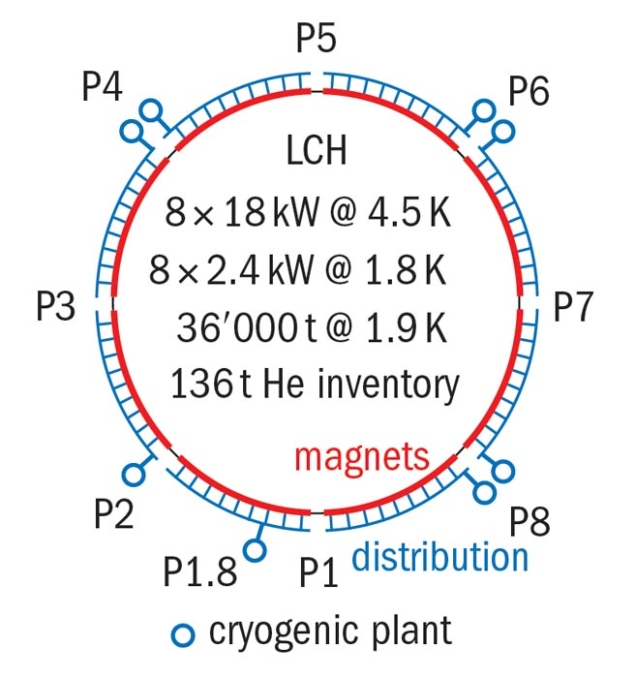

Another important improvement for the silicon detectors concerns the cooling. The evaporative cooling system that was based on a complex compressor plant has been satisfactory, even if it has created a variety of problems and interventions. The system allowed operating temperatures to be set to –20 °C with the possibility of going down to –30 °C, although the lower value has not been used so far as radiation damage to the detector is still in its infancy. However, the compressor plant needed continual attention and maintenance. The decision was therefore taken to build a second plant that was based on the thermosyphon concept, where the pressure that is required is obtained without a compressor, using instead the gravity advantage offered by the 90-m-deep ATLAS cavern. The new plant has been built and is now being commissioned, while the original plant has been refurbished and will serve as a redundant (back-up) system. In addition, the IBL cooling is based on CO2 cooling technology and a new redundant plant is being built to be ready for the IBL operations.

Both the semiconductor tracker and the pixel detector are also being consolidated. Improvements are being made to the back-end read-out electronics to cope with the higher luminosities that will go beyond twice the LHC design luminosity.

Image credit: B Di Girolamo.

Lifting the small muon wheel to the surface – an operation that had never been done before – was a success. The operation was not without difficulties because of the limited amount of space for manoeuvering the 140-tonne object to avoid collisions with other detectors, crates and the walls of the cavern and access shaft. Nevertheless, it was executed perfectly thanks to highly efficient preparation and the skill of the crane drivers and ATLAS engineers, with several dry runs done on the surface. Not to miss the opportunity, the few problematic cathode-strip chambers on the small wheel that was lifted to the surface will be repaired. A specialized tool is being designed and fabricated to perform this operation in the small space that is available between the lifting frame and the detector.

Many other tasks are foreseen for the muon spectrometer. The installation of a final layer of chambers – the endcap extensions – which was staged in 2003 for financial reasons has already been completed. These chambers were installed on one side of the detector during previous mid-winter shutdowns. The installation on the other side has now been completed during the first three months of LS1. In parallel, a big campaign to check for and repair leaks has started on the monitored drift tubes and resistive-plate chambers, with good results so far. As soon as access allows, a few problematic thin-gap chambers on the big wheels will be exchanged. Construction of some 30 new chambers has been under way for a few months and their installation will take place during the coming winter.

At the same time, the ATLAS collaboration is improving the calorimeters. New low-voltage power supplies are being installed for both the liquid-argon and tile calorimeters to give a better performance at higher luminosities and to correct issues that have been encountered during the past three years. In addition, a broad campaign of consolidation of the read-out electronics for the tile calorimeter is ongoing because it is many years since it was constructed. Designing, prototyping, constructing and testing new devices like these has kept the ATLAS calorimeter community busy during the past four years. The results that have been achieved are impressive and life for the calorimeter teams during operation will become much better with these new devices.

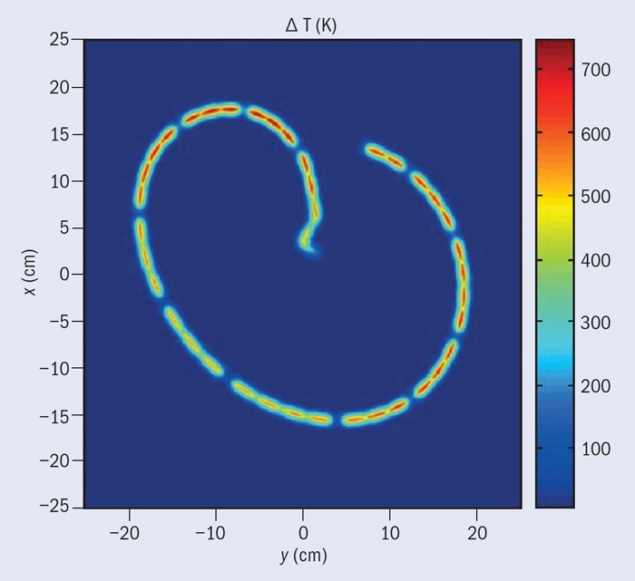

Improvements are also under way for the ATLAS forward detectors. The LUCID luminosity monitor is being rebuilt in a simplified way to make it more robust for operations at higher luminosity. All of the four Roman-pot stations for the absolute luminosity monitor, ALFA, located at 240 m from the centre of ATLAS in the LHC tunnel, will soon be in laboratories on the surface. There they will undergo modifications to implement wake-field suppression measures that will fight against the beam-induced increase in temperature that was suffered during operations in 2012. There are other plans for the beam-conditions monitor, the diamond-beam monitor and the zero-degree calorimeters. The activities are non-stop everywhere.

The infrastructure

All of the above might seem to be an enormous programme but it does not touch on the majority of the effort. The consolidation work spans the improvements to the evaporative cooling plants that have already been mentioned to all aspects of the electrical infrastructure and more. Here are a few examples from a long list.

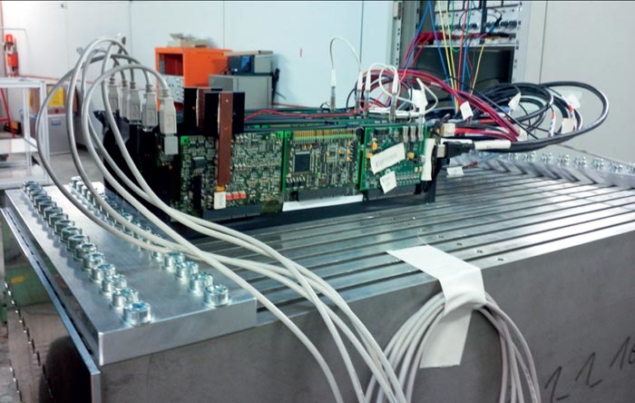

Image credit: H Pernegger.

Installation of a new uninterruptible power supply is ongoing at Point 1, together with replacement of the existing one. This is to avoid power glitches, which have affected the operation of the ATLAS detector on some occasions. Indeed, the whole electrical installation is being refreshed.

The cryogenic infrastructure is being consolidated and improved to allow completely separate operation of the ATLAS solenoid and toroid magnets. Redundancy is implemented everywhere in the magnet systems to limit downtime. Such downtime has, so far, been small enough to be unnoticeable in ATLAS data-taking but it could create problems in future.

All of the beam pipes will be replaced with new ones. In the inner detector, a new beryllium pipe with a smaller diameter to allow space for the IBL has been constructed and installed already in the IBL support structure. All of the other stainless-steel pipes will be replaced with aluminium ones to improve the level of background everywhere in ATLAS and minimize the adverse effects of activation.

A back-up for the ATLAS cooling towers is being created via a connection to existing cooling towers for the Super Proton Synchrotron. This will allow ATLAS to operate at reduced power, even during maintenance of the main cooling towers. The cooling infrastructure for the counting rooms is also undergoing complete improvement with redundancy measures inserted everywhere. All of these tasks are the result of a robust collaboration between ATLAS and all CERN departments.

LS1 is not, then, a period of rest for the ATLAS collaboration. Many resources are being deployed to consolidate and improve all possible aspects of the detector, with the aim of minimizing downtime and its impact on data-taking efficiency. Additional detectors are being installed to improve ATLAS’s capabilities. Only a few of these have been mentioned here. Others include, for example, even more muon chambers, which are being installed to fill any possible instrumental cracks in the detector.

All of this effort requires the co-ordination and careful planning of a complicated gymnastics of heavy elements in the cavern. ATLAS will be a better detector at the restart of LHC operations, ready to work at higher energies and luminosities for the long period until LS2 – and then the gymnastics will begin again.