With CERN as his scientific home since 1961, Carlo Rubbia is unique in the organization. One of the three Nobel laureates who received their prizes for research done at the laboratory, he was also director-general from 1989 to 1993 – during the crucial years when the ground for the future LHC was prepared. Rubbia’s fame, both at CERN and worldwide, is related closely to his work in the early 1980s, when the conversion of the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) to a proton–antiproton collider led to the discovery of the W and Z bosons. The Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded in 1984 jointly to Rubbia and Simon van der Meer “for their decisive contributions to the large project, which led to the discovery of the W and Z field particles, communicators of weak interaction”.

However, Rubbia is much more than an exceptional CERN physicist awarded a Nobel prize, who also became director-general. As a child he was forced to flee his home in Gorizia in north-eastern Italy during the Second World War. He went on to become a brilliant physics student at Scuola Normale in Pisa, after almost taking up engineering; a scientist who continues to push the frontiers of knowledge; a volcano of ideas whose inextinguishable fuel is his relentless curiosity and vision; and a courageous citizen of the world, convinced of the duty of science to find solutions to today’s global emergencies. In August 2013, the president of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, recognized Rubbia’s contribution to the history and prestige of CERN, and to a field “vital to our country”, as he put it, when he appointed Rubbia “senator for life” (CERN Courier November 2013 p37).

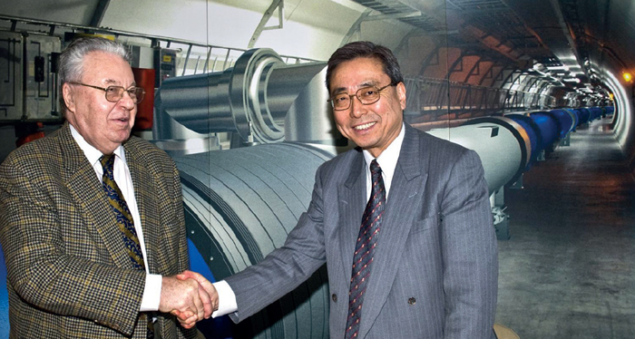

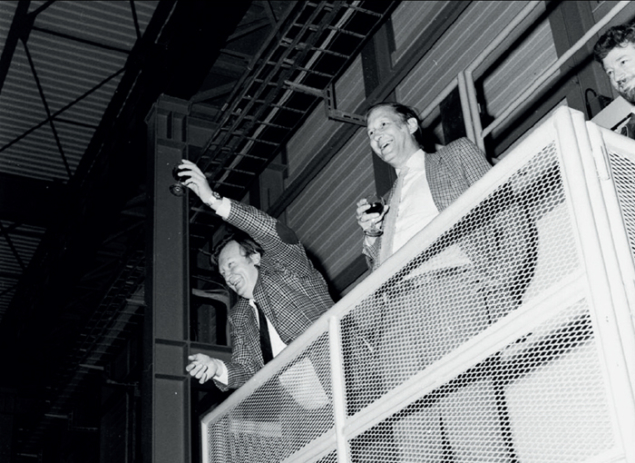

Image credit: CERN HI 47.12.91/5.

The path that would take Carlo Rubbia to Stockholm for the Nobel prize started in the Scuola Normale in Pisa, just one year before CERN was founded, in September 1953. There he chose physics against the will of his parents.

My family would have preferred that I took engineering, but I wanted to study physics. So we agreed that if I passed the entrance exams for the Scuola Normale in Pisa, I could study physics there, otherwise I would have to do engineering. There were only 10 places for Pisa, and I was ranked 11th, so I lost – and I started engineering at Milan. Luckily an unknown student among the first 10 in Pisa (whom I’d be curious to meet one day) gave up and left a place open to the next applicant on the waiting list. So, three months later, I was in Pisa, studying physics, and I stayed there and had a lot of fun.

It’s not unusual to hear research physicists speak about their job in terms of “fun”. In Rubbia’s case, physics is still a huge part of his life and is a real passion. Why is this?

“New” is the keyword. Discovering something new creates alternatives, generates interest and fuels the world. The future is not repeating what you’ve done in the past. Innovation, driven by curiosity, the desire to find out something new, is one of the fundamental attributes of mankind. We did not go to the Moon because of wisdom, but because of curiosity. This is part of human instinct, it is true for all civilizations, and is unavoidable.

After obtaining his degree from Pisa in 1957 in record time – three years, including the doctoral thesis – Rubbia spent a year on research at Columbia University in the US, followed by a year at La Sapienza university in Rome as assistant professor to Marcello Conversi – whom he remembers as “a great friend in addition to being a great mentor, someone with whom the transition from student to colleague happened very smoothly” – before landing at CERN in 1961.

I thought Europe was the real future for someone who wanted to do research. Europe needed to resurrect in science in general, and physics in particular. [After the US] my interest was not in going back to Italy, but rather to go back to Europe. So I left Rome after a year of teaching and went to CERN.

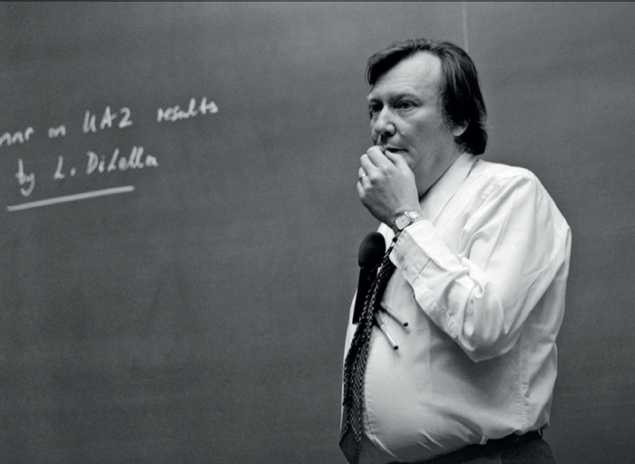

Image credit: CERN-HI-8410523.

When Rubbia arrived, CERN’s active laboratory life was just beginning.

When I arrived, none of the buildings you see today were there. There was no cafeteria. We took coffee and our meals at a restaurant near the airport [Le Café de l’Aviation] and the University of Geneva offered us space to carry out our work while CERN was under construction. In this group of CERN pioneers there were also two others who received the Nobel prize: Simon van der Meer and Georges Charpak. All three of us were among the few who have experienced CERN since its early days.

CERN was the stage for Rubbia’s greatest scientific adventure, which led to the discovery of the W and Z bosons. He convinced the director-general at the time – John Adams – to modify the programme of the SPS and transform it into a proton–antiproton collider, with technology that all had to be developed.

My first proposal was written for the US, because I was teaching at Harvard and therefore part of the US system – the most advanced research system in the world at the time. But this did not work for a number of reasons, among them the bureaucracy that was starting to grow there. CERN was a new place, there were people like Léon van Hove and John Adams who had a vision for the future, and they supported my idea that soon became a possible solution. Clearly this kind of idea involves a lot of pressure, hard work, and competition with alternative ideas. There were many competing projects, all aiming to become the new big project for CERN, for which there were funds. Bjorn Wiik wanted to make an electron–proton machine, Pierre Darriulat was pushing for a super-ISR, a superconducting one. All of these ideas were part of a purely scientific debate, without any political influence, and this was very healthy.

Making collisions between two beams, especially between protons and antiprotons, required enormous development, but not that many people. The number of people who developed the proton–antiproton collider – I mean those who made a real intellectual contribution, those who did 99% of the work – were no more than a dozen. We were looking for an answer to a very specific question and we had a very clear idea of what we were looking for.

I left an LHC minus the SSC to the CERN community

Rubbia’s next big challenge after the discovery of the W and Z bosons was his mandate as CERN’s director-general, from January 1989 to December 1993, at a crucial time for setting up CERN’s next big project – the LHC.

The name LHC was invented by us – by myself and a small group of people around me. I remember Giorgio Brianti saying that the acronym LHC could not be used, because it already meant Lausanne Hockey Club, which was, at the time, much more popular for the lay public than a machine colliding high-energy protons. Nowadays things are quite different! We started with a programme that was much less ambitious than the US programme. The Americans were still somehow “cut to the quick” by our proton–antiproton programme, so they had started the SSC project – the Superconducting Super Collider – which would be a huge machine, a much more expensive one, but which was later abandoned. So, when my mandate as director-general finished, I left an LHC minus the SSC to the CERN community.

On 4 July 2012, when CERN announced to the world the discovery of “a new boson”, 30 years after his discovery of the W and Z bosons, Rubbia’ s reaction – from the press conference held at the annual Nobel gathering in Lindau that he was attending – was as enthusiastic as ever.

“This result is remarkable, no question. To get the line at 125 GeV – or 150 protons in terms of mass – which is extremely narrow, has a width of less than 1%, and comes out exactly with a large latitude of precision, with two independent experiments that have done the measurements separately and found the same mass and the same very, very narrow width…well, it’s a fantastic experimental result! It doesn’t happen every day. The last time, as far as I know, was when we discovered the W and Z at CERN and the top at Fermilab. We are in front of a major milestone in the understanding of the basic forces of nature.”

The basic forces of nature are not the only fodder to feed Rubbia’s inextinguishable curiosity and craving for innovation. After his mandate as CERN’s director-general finished at the end of 1993, he fought to bring accelerator technology to a variety of fields, from the production of “sustainable” nuclear energy to the production of new radioisotopes for medicine, from a new engine to shorten interplanetary journeys to innovative solar-energy sources.

“Homo” is essentially “faber” – born to build, to make. Today there are many things that need development and innovation. One of the most urgent problems we have is that the population on our planet is growing too fast. Since I was born, the number of people on Earth has multiplied by a factor of three, but the energy used has grown as the square of the number of people, because each of us consumes more energy. We know today that the primary energy produced is 10 times the quantity produced when I was born – and the planet is paying a price. So I find it normal to wonder, where are we going in the future? Will the children born today have 10 times the energy produced today? Will we have three times the population of today? This is the famous reasoning started by Aurelio Peccei, founder of the Club of Rome – the well-known “limits to growth”, discussed in Italy at least a quarter of a century ago. This is still an important issue and it’s all about energy. And this opens up the question of nuclear energy – the old one versus the new one.

Image credit: CERN-PHOTO-8301284.

Clearly, nuclear energy has gone through a lot of development, but still the nuclear energy that we have today is fundamentally the same as yesterday’s, based on the ideas brought about by Enrico Fermi in the 1940s. It’s part of the era of the Cold War, of development projects for nuclear energy as a weapon rather than basic research. Today the stakes have changed. So if we want to use nuclei to make energy, which we should, we have to do it on a different basis, with elements and conditions that are fundamentally different from yesterday’s. Three aspects of yesterday’s/today’s nuclear energy are worrying: Hiroshima, Chernobyl, and, more recently, Fukushima is also now part of the family of disasters. And of course there’s the problem of radioactive waste. These aspects are no longer manageable in the same way that they were during the Cold War’s golden era. We obviously have to change. And it’s the scientist’s task to improve things. Planes in the 1940s and 1950s scared everybody. My father never boarded a plane. Today everyone does. Why? Because we accepted and modified the technology to make planes super safe. We have to make nuclear energy super safe.

How does someone who has witnessed the entire history of CERN – often first-hand – see its future, and the future of physics?

The LHC brought an enormous change to CERN, whereby today the collaboration with the rest of the world, with non-European countries like the US and Japan, is rather a co-operation than a competition. The LHC transformed CERN from a European laboratory into the main laboratory for an entire research field across the whole world. But this is not without disadvantages, because competition has its benefits. Having a single world-laboratory doing a specific thing is a big risk. If there is only one way of doing things, there is no alternative, unless alternatives come from the inside. But alternatives coming from the inside have a difficult life because the feeling of continuity prevails over innovation. Fortunately, we have an experimental programme and all the elements are now there to conduct high-precision research, and we are on the verge of turning a new page.

I do not know what the next page will be and I would prefer to let nature decide what we physicists will find next. But one thing is clear: with 96% of the universe still to be fathomed, we are faced with an absolutely extraordinary situation, and I wonder whether a young person who wants to study physics today, and is told that 96% of the mass and energy of the universe is yet to be understood, feels excited. Obviously they should feel as excited as I did when I was told about elementary particles. Innovative knowledge, the surprise effect, exists today, still continues to exist and is very strong, provided there are people capable of perceiving it.

CERN will have to choose a new director-general soon. If you had a chance to take that position again, what would your policy for the laboratory be?

I always said that physics at CERN has to be “broad band”. It cannot be “narrow band”. Transforming the SPS into a p–p collider and cooling antiprotons were not part of the programme, and we had the flexibility and freedom to do it. We built the LHC while LEP was still functioning – that was a broad-band scientific policy. The problem is, you never know where the next discovery will come from! Our field is made of surprises, and only a broad-band physics programme can guarantee the future of CERN.