Image credit: Henry Barnard/CERN.

Shake hands with Eleanor Blakely and you are only one handshake away from John Lawrence – a pioneer of nuclear medicine and brother of Ernest Lawrence, the Nobel-prize-winning inventor of the cyclotron, the first circular particle accelerator. In 1954 – the year that CERN was founded – John Lawrence began the first use of proton beams from a cyclotron to treat patients with cancer. Twenty years later, as a newly fledged biophysicist, Blakely arrived at the medical laboratory that John had set up at what is now the Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. There she came to know John personally and was to become established as a leading expert in the use of ion beams for cancer therapy.

With ideas of becoming a biology teacher, Blakely went to the University of San Diego in 1965 to study biology and chemistry. While there, she spent a summer as an intern at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and developed an interest in radiation biology. Excelling in her studies, she was encouraged to move towards medicine after obtaining her BA in 1969. However, armed with a fellowship from the Atomic Energy Commission that allowed her to choose where to go next, she decided to join the group of Howard Ducoff, a leading expert in radiation biology at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Because she was fascinated by basic biological mechanisms, Ducoff encouraged her to take up biophysics, a field so new that he told her that it was “whatever you want to make it”. A requirement of the fellowship was to spend time at a national laboratory, so Blakely was assigned a summer at Berkeley Laboratory, where she worked on NASA-funded studies of proton radiation on murine skin and subsequent changes in blood electrolytes, which led to a Masters’ degree in biophysics.

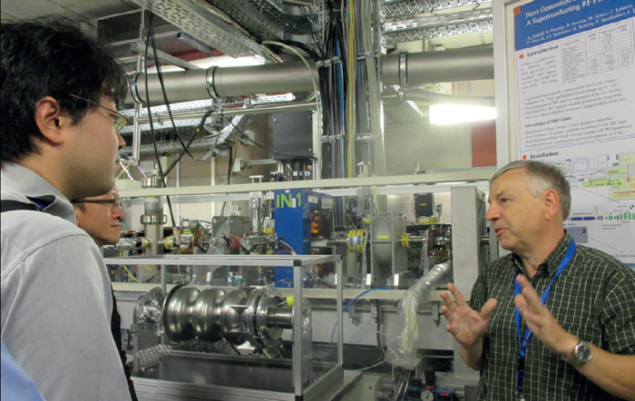

After gaining her PhD studying the natural radioresistance of cultured insect cells, Blakely joined the staff at Berkeley Lab in 1975, arriving soon after the Bevatron – the accelerator where the antiproton was discovered – had been linked up to the heavy-ion linear accelerator, the SuperHILAC. The combination, known as the Bevalac, could accelerate ions as heavy as uranium to high energies. Blakely joined the group led by Cornelius Tobias. His research included studies related to the effects of cosmic rays on the retina, for which he exposed his own eye to ion beams to confirm his explanation of why astronauts saw light flashes during space flight. “It was a spectacular beginning, seeing my boss getting his eye irradiated,” Blakely recalls. For her own work, Tobias showed her a theoretical plot of the stopping power versus range for the different ion beams available at Berkeley. Her task was to work out which would be the best beam for cancer therapy. “I had no idea how much work that was going to be,” she says, “and it is still not settled!”

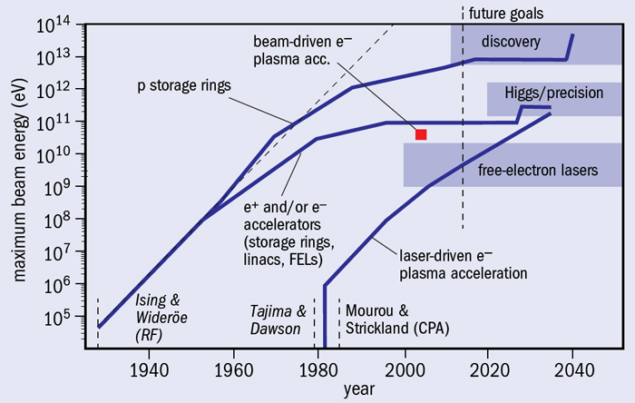

Thirty years before Blakely arrived at Berkeley, Robert Wilson, later founding director of Fermilab, had been working there with Ernest Lawrence when he realized that because protons and heavier ions deposit most of their energy near the end of their range in matter – the famous “Bragg peak” – they offered the opportunity of treating deep-seated tumours while minimizing damage to surrounding tissue (CERN Courier December 2006 p17). Assigned the task of studying the biological effectiveness of a variety of particles and energies available from Berkeley’s accelerators, Blakely irradiated dishes of human cell cultures, working along increasing depths of the Bragg peak for the various beams under different conditions. In particular, by spreading the energy of the incident particles the team could broaden the Bragg peak from a few millimetres to several centimetres.

The studies revealed that for carbon and neon ions, in the region before the Bragg peak there was a clear difference in cell survival under aerobic (oxygen) or hypoxic (nitrogen) conditions, while in the Bragg peak the relative biological effectiveness, as measured by cell survival, was more independent of oxygen than for X-rays or γ rays (Blakely et al. 1979). This boded well for the use of these ions in treating tumours, because many tumour cells are resistant to radiation damage under hypoxic conditions. For argon and silicon, however, the survival curves in oxygen and nitrogen already indicated high cell killing and a reduced oxygen effect in the entrance region of the Bragg curve before the peak, indicating that at higher atomic number, these ions were already too damaging and did not afford the radioprotection of the particles with lower atomic number in the beam entrance. The work had important ramifications for the development of hadron therapy today: while Berkeley went on to use neon ions for treatments, therapy with carbon ions was to become of major importance, first in Japan and then in Europe (CERN Courier December 2011 p37).

At Berkeley, she was plunged into a world of physics. “I had to learn to talk to physicists,” she recalls. “I had only basic physics from school – I learnt a lot of particle physics.” And in common with many physicists, it is a desire to understand how things work that has driven Blakely’s research, with the added attraction of being able to help people. Her interest lies deep in the cell cycle and what happens to the DNA, for example, as a function of radiation exposure. While her work has been of great value in helping oncologists, it is the fundamental processes that fascinate her as “a bench-top scientist”, to use her own words. “I’m interested in the body’s feedback mechanisms,” she explains.

That does not reduce her humanity. Some of the treatments at Berkeley used a beam of helium ions directed through the lens to destroy tumours of the retina. Blakely was devastated to learn that although the tumour was destroyed, the patients developed cataracts – a late radiation effect of exposure to the lens adjacent to some retinal tumours, which required lens-replacement surgery. As a result, she not only helped to propose a more complex technique to irradiate the tumours by directing the beam though the sclera (the tough, white outer layer of the eye) instead of the lens, but also became interested in the effects of radiation on the lens of the eye – a field in which she is a leading expert.

In 1993, the Bevalac was shut down, leaving Blakely and her colleagues at Berkeley without an accelerator with energies high enough for hadron therapy. “It was such an old machine,” she says. “Everyone had worked their hearts out to treat the patients.” The Bevalac had produced the heavier ion beams, while the 184-inch accelerator had produced beams of helium ions, and together almost 2500 cancer patients had been treated.

With her interest in irradiation of the eye, Blakely followed her first group leader “into space” – at least as a “bench-top” scientist – with studies of the effects of low radiation doses for the US space agency, NASA. “In space, people are exposed to chronic low doses of radiation,” she explains. In particular, she has been studying heavy-ion-induced tumourigenesis in mice with a broad gene pool similar to humans, to evaluate any risks in space travel.

Given that hadron therapy began 60 years ago at Berkeley, it is striking that nowadays there are no treatment centres in the US that use nuclei any heavier than the single protons of hydrogen. Japan was the first country to have a heavy-ion accelerator built for medical purposes – the Heavy Ion Medical Accelerator in Chiba (HIMAC) that started in 1994 (CERN Courier July/August 2007 p17 and June 2010 p22). During the last 10 years, Europe has followed suit, with the Heidelberg Ion-Beam Therapy Centre in Germany, and the Centro Nazionale di Adroterapia Oncologica in Italy using carbon-ion beams on an increasing number of patients (CERN Courier December 2011 p37). Another new centre, MedAustron in Austria, is now reaching the commissioning phase (CERN Courier October 2011 p33). Blakely describes the situation in her homeland as “a tragedy – the technology emerged from the US but we don’t have the machines”. Part of the problem lies with the country’s health-care plan, she says. “The treatments are not yet reimbursable, and the government won’t support building machines.”

Nevertheless, there is a glimmer of hope, following a workshop on ion-beam therapy organized by the US Department of Energy and the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda in January 2013, with participants from medicine, physics, engineering and biology. P20 Exploratory Planning Grants for a National Center for Particle Beam Radiation Therapy Research in the US are now pending. “Sadly this doesn’t give us money to build a machine – legally the government isn’t allowed to do that – but the P20 can provide for infrastructure, research and networking once you have a machine,” Blakely explains. However, there is support for patients from the US to take part in randomized clinical trials – the “gold standard” for determining the best modality for treating a patient. At the same time, she envies the networking and other achievements of the European Network for Light Ion Hadron Therapy (ENLIGHT), co-ordinated at CERN, which promotes international R&D, networking and training (CERN Courier December 2012 p19). “Networking is really import but it wasn’t something they taught us at school,” she says, “and training for students and staff is essential for the use of hadron therapy to have a future….The many programmes that have been developed [by ENLIGHT] are extremely important and valuable, and I wish we had them in the US.”

Looking back on a career that spans 40 years, Blakely says: “It has been fulfilling, but a lot of work.” And what aspect is she most proud of? “Probably the paper from 1979,” she answers, “the result of many nights working at the accelerator.” When the focal point of hadron therapy moved to Japan, researchers there repeated her work. “They found the data were exactly reproducible,” she says with clear pleasure. Would she recommend the same work to a young person today? “With the current funding situation in the US,” she says, “I tell people that you have to love it more than eating – you need to be really committed.” Perhaps, one day, hadron therapy will return home, and the line of research begun by pioneers such as John Lawrence and Cornelius Tobias will inspire a new generation of people like Blakely.