By Cecilia Jarlskog (ed.)

Springer

Hardback: £62.99 €74.89

E-book: £49.99 €59.49

This book is extremely interesting. Mainly a collection of testimonies, it helps in understanding the special personality of Gunnar Källén – his kindness and aggressiveness. Cecilia Jarlskog is named as “editor”, but she is more than an editor in having written an informative biography.

Källén worked in the “Group of Theoretical Studies” – one of three groups that were set up as part of the “provisional CERN” in 1952 – which was based in Copenhagen until it was officially closed in 1957. He later became professor at Lund University, and tragically died in 1968 when his plane crashed while he was flying it from Malmö to CERN.

I was impressed by Steve Weinberg’s admiration for Källén – he considers himself a student of Källén, although he was Sam Treiman’s student – as well as by that of James Bjorken and Wolfgang Pauli, who wanted Källén as professor at ETH Zurich. I cannot comment on the fact that it was finally Res Jost who was appointed, because I have the highest esteem for him also.

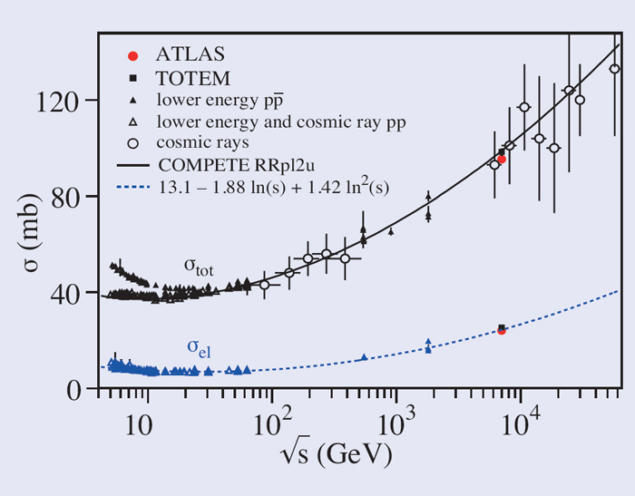

It is interesting that Pauli disapproved of Källén’s work on the n-point function. It was only long after Pauli’s death that Källén quit this subject, and took a 90° turn with the writing of his book on elementary particles. It is true that Källén failed, while being critical of Jacques Bros, Henri Epstein and Vladimir Glaser because they were not using invariants. However, Bros–Epstein–Glaser succeeded and proved crossing symmetry, allowing proof of the Froissart bound without dispersion relations, and providing a starting point for the Pomeranchuk theorem.

Because the book is based on testimonies, there is a certain redundancy, in particular about the accident, but this is unavoidable. Overall, Cecilia Jarlskog has done an excellent job. The plane crash was a tragedy, and if he had lived, Källén would certainly have made further important contributions. (His two passengers – his wife Gunnel and Matti von Dardel – survived the crash. Matti has told me that her husband Guy von Dardel and Källén were planning a collaboration between a theoretician and an experimentalist. The accident put an end to that.)