By Valery Lebedev and Vladimir Shiltsev (eds)

Springer

Hardback: £99 €116.04 $149

E-book: £79 €91.62 $119

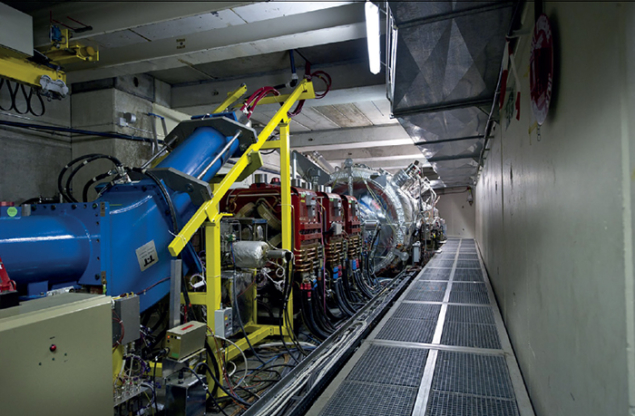

This fascinating book, compiled and edited by two of the leaders of Tevatron’s Run II, describes the achievements and lessons from Fermilab’s famous machine, which shut down for the last time at the end of September 2011. The authors and editors take us on a mesmerizing tour through the components and history of this remarkable accelerator, and provide a lively account of how, across the years, numerous obstacles were overcome, and how novel technologies contributed to the astonishing success of “one of the most complex research instruments ever to reach the operation stage”. Not only was the Tevatron the highest-energy particle collider for about a quarter of a century, it was also a pioneering accelerator in almost every regard.

In the first of nine chapters, Steve Holmes, former Fermilab accelerator director, John Peoples, former Fermilab director, together with Ronald Moore and Vladimir Shiltsev, recall the history of Fermilab and the “Energy Saver/Doubler”, which was later to become known as the Tevatron. Across almost three decades, the peak luminosity of this collider was increased by four orders of magnitude. The second chapter, in which Alexander Valishev joins the two editors as author, surveys the Tevatron’s linear and nonlinear beam-optics control. I particularly enjoyed the review of the intricate and spectacular nonlinear dynamics experiments performed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which had been conceived to unveil the origin of dynamic aperture (e.g., the famous “E778 experiment”) and the effect of tune modulation.

The third chapter, by Jerry Annala and co-workers, brings us to the heart of the accelerator. As the first superconducting hadron storage ring, the Tevatron designers and operators had many issues to tackle. These included the effects of large intrinsic nonlinear field errors; the dynamic chromaticity drifts owing to the decay of persistent-current field errors, whose successful automatic compensation depended on many details of the preceding magnet cycles, such as the length of the flat top, the ramp rate, etc; and, last but not least, the “snapback” – i.e. the sudden re-induction of the persistent currents in the superconducting cable at the start of the energy ramp. From my student days, I vividly remember how much the Tevatron experience guided the development of the later superconducting machines, such as HERA at DESY. This chapter also presents the Recycler, the first large-scale all-permanent-magnet storage ring, operating at 8 GeV.

In the following chapter, Chandra Bhat, Kiyomi Seiya and Shiltsev present two of the most fascinating techniques of longitudinal beam manipulation – slip stacking, which has doubled the proton intensity in the Main Injector, and radiofrequency barrier buckets, used for the accumulation and processing of antiprotons. Next, Alexey Burov, Lebedev and their colleagues discuss the Tevatron’s impedance and collective effects. There are noteworthy handy formulae for the transverse and longitudinal impedance of laminated vacuum chambers developed for the Tevatron, which I have used myself often.

Chapter six, by Richard Carrigan and several co-authors, treats mechanisms of emittance growth and beam loss, including important mitigation measures such as collimation, beam removal from the abort gap using the “Tevatron electron lens” as a pulsed exciter, tests of halo deflection with bent crystals, and the Tevatron luminosity model. Lebedev, Ralph Pasquinelli and others then delve into antiproton production, stochastic cooling and the first relativistic electron cooler, based on a 4.3 MV pelletron, which many of my colleagues had thought to be unfeasible. The antiproton source technology, which had begun at CERN, was brought to maturity at the Tevatron complex, where from 1994 to 2010 the antiproton intensity was raised by another factor of 10, making this the most powerful antiproton source constructed, by far. In chapter eight, Shiltsev and Valishev discuss beam–beam effects, including the famous “scallop”-shaped pattern of emittance growth along the antiproton bunch trains, which I witnessed myself fill after fill around the year 2002, while visiting the Tevatron control room. Finally, advanced beam instrumentation, including Schottky monitors and proton synchrotron-light diagnostics, are summarized in chapter nine.

At the end of the book I found a list of about 30 PhD theses, completed on accelerator-physics topics at the Tevatron across a span of about 25 years. I smiled when I realized that many of these earlier PhD students have become today’s leaders in the accelerator field. This illustrates the exceptional training experience from participating in a demanding and inspiring collider programme such as the Tevatron’s.

Undoubtedly, this book will serve as a wonderful and unique reference for many decades to come. The authors and editors are to be congratulated for their effort to compile and preserve the accelerator knowledge of the Tevatron, accumulated during 25 years of successful struggle and permanent innovation. The Tevatron’s lessons and achievements would be all too easily forgotten without such a written record. In conclusion, I recommend this book highly to accelerator professionals around the world. Reading it should be all but compulsory for anyone wishing to improve the performance of an existing frontier machine, or design the next generation of highest-energy colliders.