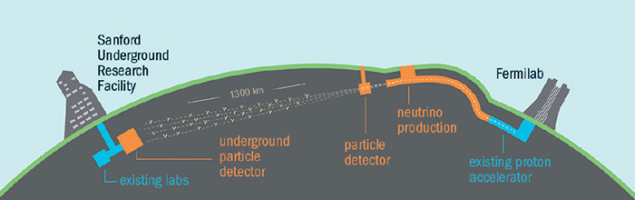

Image credit: Fermilab.

The neutrino is the most abundant matter-particle in the universe and the lightest, most weakly interacting of the fundamental fermions. The way in which a neutrino’s flavour changes (oscillates) as it propagates through space implies that there are at least three different neutrino masses, and that mixing of the different mass states produces the three known neutrino flavours. The consequences of these observations are far reaching because they imply that the Standard Model is incomplete; that neutrinos may make a substantial contribution to the dark matter known to exist in the universe; and that the neutrino may be responsible for the matter-dominated flat universe in which we live.

This wealth of scientific impact justifies an energetic programme to measure the properties of the neutrino, interpret these properties theoretically, and understand their impact on particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology. The scale of investment required to implement such a programme requires a coherent, international approach. In July 2013, the International Committee for Future Accelerators (ICFA) established its Neutrino Panel for the purpose of promoting both international co-operation in the development of the accelerator-based neutrino-oscillation programme and international collaboration in the development of a neutrino factory as a future intense source of neutrinos for particle-physics experiments. The Neutrino Panel’s initial report, presented in May 2014, provides a blueprint for the international approach (Cao et al. 2014).

The accelerator-based contributions to this programme must be capable both of determining the neutrino mass-hierarchy and of seeking for the violation of the CP symmetry in neutrino oscillations. The complexity of the oscillation patterns is sufficient to justify two complementary approaches that differ in the nature of the neutrino beam and the neutrino-detection technique (Cao et al. 2015). In one approach, which is adopted by the Hyper-K collaboration, a neutrino beam of comparatively low energy and narrow energy spread (a narrow-band beam) is used to illuminate a “far” detector at a distance of approximately 300 km from the source (see “Proto-collaboration formed to promote Hyper-Kamiokande”). In a second approach, a neutrino beam with a higher energy and a broad spectrum (a wide-band beam) travels more than 1000 km through the Earth before being detected.

Since summer 2014, a global neutrino collaboration has come together to pursue the second approach, using Fermilab as the source of a wide-band neutrino beam directed at a far detector located deep underground in South Dakota. In addition to measuring the neutrinos in the beam, the experiment will study neutrino astrophysics and nucleon decay. This experiment will be of an unprecedented scale and dramatically improve the understanding of neutrinos and the nature of the universe.

This new collaboration – currently dubbed ELBNF for Experiment at the Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility – has an ambitious plan to build a modular liquid-argon time-projection chamber (LAr-TPC) with a fiducial mass of approximately 40 kt as the far detector and a high-resolution “near” detector. The collaboration is leveraging the work of several independent efforts from around the world that have been developed through many years of detailed studies. These groups have now converged around the opportunity provided by the megawatt neutrino-beam facility that is planned at Fermilab and by the newly planned expansion with improved access of the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota, 1300 km from Fermilab. To give a sense of scale, to house this detector some 1.5 km underground requires a hole that is approximately 120,000 m3 in size – nearly equivalent to the volume of Wimbledon’s centre-court stadium.

The principal goals of ELBNF are to carry out a comprehensive investigation of neutrino oscillations, to search for CP-invariance violation in the lepton sector, to determine the ordering of the neutrino masses and to test the three-neutrino paradigm. In addition, with a near detector on the Fermilab site, the ELBNF collaboration will perform a broad set of neutrino-scattering measurements. The large volume and exquisite resolution of the LAr-TPC in its deep underground location will be exploited for non-accelerator physics topics, including atmospheric-neutrino measurements, searches for nucleon decay, and measurement of astrophysical neutrinos (especially those from a core-collapse supernova).

The new international team has the necessary expertise, technical knowledge and critical mass to design and implement this exciting “discovery experiment” in a relatively short time frame. The goal is the deployment of a first detector with 10 kt fiducial mass by 2021, followed by implementation of the full detector mass as soon as possible. The accelerator upgrade of the Proton Improvement Plan-II at Fermilab will provide 1.2 MW of power by 2024 to drive a new neutrino beam line at the laboratory. There is also a plan that could further upgrade the Fermilab accelerator complex to enable it to provide up to 2.4 MW of beam power by 2030 – an increase of nearly a factor of seven on what is available today. With the possibility of space for expansion at the Sanford Underground Research Facility, the new international collaboration will develop the necessary framework to design, build and operate a world-class deep-underground neutrino and nucleon-decay observatory. This plan is aligned with both the updated European Strategy for Particle Physics and the report of the Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel (P5) written for the High Energy Physics Advisory Panel in the US.

A letter of intent (LoI) was developed during autumn 2014, and the first collaboration meeting was held in mid January at Fermilab. Sergio Bertolucci, CERN’s director for research and computing, and interim chair of the institutional board, ran the meeting. More than 200 participants from around the world attended, and close to 600 physicists from 140 institutions and 20 countries have signed the LoI, to date. The collaboration has chosen its new spokespersons – Mark Thomson of Cambridge University and André Rubbia of ETH Zurich – and will begin the process of securing the early funding needed to excavate the cavern in a timely fashion so that detector installation can begin in the early 2020s.

Mounting such a significant experiment on such a compressed time frame will require all three world regions – Asia, the Americas and Europe – to work in concert. The pioneering work on the liquid-argon technique was carried out at CERN and implemented in the ICARUS detector, which ran for many years at Gran Sasso. To deliver the ELBNF far detector requires that the LAr-TPC technology be scaled up to an industrial scale. To deliver the programme required to produce the large LAr-TPC, neutrino platforms are being constructed at Fermilab and at CERN. A team led by Marzio Nessi is working hard to make this resource available at CERN and to complete in the next few years the R&D needed for both the single- and dual-phase liquid-argon technologies that are being proposed on a large scale (see box).

The steps taken by the neutrino community during the nine months or so since summer 2014 have put the particle-physics community on the road towards an exciting and vibrant programme that will culminate in exquisitely precise measurements of neutrino oscillation. It will also establish in the US one of the flagships of the international accelerator-based neutrino programme called for by the ICFA Neutrino Panel. In addition, ELBNF will be a world-leading facility for the study of neutrino astrophysics and cosmology.

With such a broad and exciting programme, ELBNF will be at the forefront of the field for several decades. The remarkable success of the LHC programme has demonstrated that a facility of this scale can deliver exceptional science. The aim is that ELBNF will provide a second example of how the world’s high-energy-physics community can come together to deliver an amazing scientific programme. New collaborators are still welcome to join in the pursuit.

• In March the new collaboration chose the name DUNE for Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment.

ICARUS and WA105

The ICARUS experiment, led by Carlo Rubbia, employs the world’s largest (to date) liquid-argon detector, which was built for studies of neutrinos from the CNGS beam at CERN. The ICARUS detector with its 600 tonnes of liquid argon took data from 2010 to 2012 at the underground Gran Sasso National Laboratory. ICARUS demonstrated that the liquid-argon detector has excellent spatial and calorimetric resolution, making for perfect visualization of the tracks of charged particles. The detector has since been removed and taken to CERN to be upgraded prior to sending it to Fermilab, where it will begin a new scientific programme.

For more than a decade, the neutrino community has been interested in mounting a truly giant liquid-argon detector with some tens-of-kilotonnes active mass for next-generation long-baseline experiments, neutrino astrophysics and proton-decay searches – and, in particular, for searches for CP violation in the neutrino sector. WA105, an R&D effort located at CERN and led by André Rubbia of ETH Zurich, should be the “last step” of detector R&D before the underground deployment of detectors on the tens-of-kilotonne scale. The WA105 demonstrator is a novel dual-phase liquid-argon time-projection chamber that is 6 m on a side. It is already being built, and should be ready for test beam by 2017 in the extension of CERN’s North Area that is currently under construction