Image credit: Muhammad Imran/NCP.

In September 1954, the European Organization for Nuclear Research – CERN – officially came into existence. This was just nine years after the Second World War, when Europe was completely divided and torn apart. Founders of CERN hoped that “it would play a fundamental role in rebuilding European physics to its former grandeur, reverse the brain drain of the brightest and best to the US, and continue and consolidate post-war European integration”. Today, as one of the outstanding high-energy physics laboratories in the world, CERN has not only more than fulfilled the goals of its founders, but is also a laboratory for thousands of physicists and engineers from all over the world.

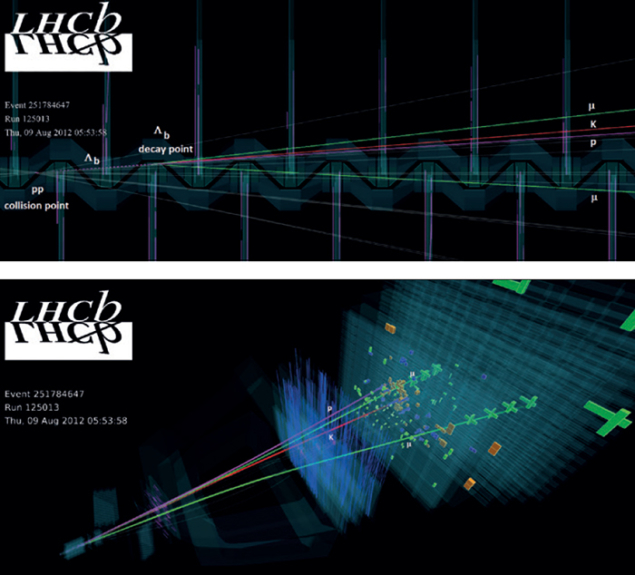

CERN is a fine example in which high technology and science reinforce both each other and international collaboration. Exploration of the unknown is the hallmark of fundamental research. This requires, on one hand, cutting-edge technology for developing detectors for the LHC, the world’s largest accelerator. On the other hand it necessitates new concepts in computer software for the storage and analysis of the enormous amount of data generated by LHC’s experiments.

On 31 July, Pakistan officially became an associate member of CERN. There is one respect in which CERN has a very special relationship with Pakistan. Experiments done at CERN in 1973 provided the first and crucial verification of one of the predictions of electroweak unification theory proposed by Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg, which resulted in the award of the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics to these three physicists. In a speech made by Salam on 11 May 1983 in Bahrain, he said: “We forget that an accelerator like the one at CERN develops sophisticated modern technology at its furthest limit. I am not advocating that we should build a CERN for Islamic countries. However, I cannot but feel envious that a relatively poor country like Greece has joined CERN, paying a subscription according to the standard GNP formula. I cannot rejoice that Turkey, or the Gulf countries, or Iran or Pakistan seem to show no ambition to join this fount of science and get their people catapulted into the forefront of the latest technological expertise. Working with CERN’s accelerators brings at the least this reward to a nation, as Greece has had the perception to realize.” Salam’s wish has now been fulfilled.

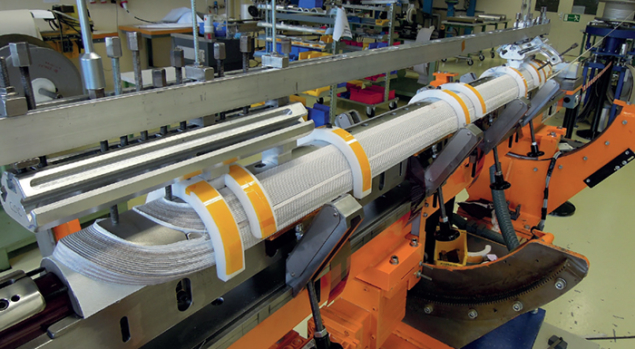

Pakistan has had an established linkage with CERN for more than two decades. The CERN–Pakistan co-operation agreement was signed in 1994. In 1997, the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission signed an agreement for an in-kind contribution worth $0.5 million for the construction of eight magnetic supports for the CMS detector. This was followed by another agreement in 2000, where Pakistan assumed responsibility for the construction of part of the CMS muon system, increasing Pakistan’s contribution to $1.8 million. Through the same agreement, the National Centre for Physics (NCP) became a full member of the CMS collaboration. In 2004, the NCP established a Tier-2 node in the Worldwide LHC Computing Grid, the first in south-east Asia.

Since then, there has been no looking back. Pakistan has contributed to all of the four big experiments at the LHC, as well as in the consolidation of the LHC accelerator itself. Above all, Pakistani physicists and hardware built in Pakistan for the CMS detector played an important role in the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, the last missing piece of the Glashow–Salam–Weinberg model.

Pakistan’s collaboration with CERN has already resulted in numerous benefits: manufacturing jobs in engineering, benefiting Pakistani industry; engineers learning new techniques in design and quality assurance, which in turn improves the quality of engineering in Pakistan; a unique opportunity for interfacing among multidisciplinary groups in academia and industry working at CERN; and working in an international environment with people from diverse backgrounds has advantages of its own.

It is hoped that CERN has also benefited from the expertise brought in by Pakistani scientists, students, engineers and technicians to save time and money. It has certainly been satisfying for Pakistan to contribute in a small way in this great enterprise.

We also plan to get involved in CERN’s future research and development projects. In particular, there is keen interest in the Pakistani physics community to participate in R&D for future accelerators. Discussions are already underway to understand where we can contribute meaningfully, keeping in mind our resources and other limitations. In particular, there is strong interest among Pakistani physicists to be involved in the R&D for a future linear collider.

In this new phase of Pakistan–CERN co-operation, which started on 19 December 2014 with the signing of the document for associate membership (CERN Courier January/February 2015 p6), the emphasis will shift to finding work opportunities at CERN for young scientists and engineers, as well as to the training of young Pakistani scientists at CERN. It will also be an opportunity for Pakistan to be more deeply involved in fundamental research in physics. For this purpose, we would involve our graduate students in work with physics groups at CERN as a part of their PhD studies. This would provide an opportunity for our young scientists and engineers to contribute to knowledge at the very frontiers of physics.