By Pauline Gagnon

Oxford

Also available at the CERN bookshop

One of my struggles when I teach at my university, or when I talk to friends about science and technology, is finding inspiring analogies. Without vivid images and metaphors it is extremely hard, or even impossible, to explain the intricacies of particle physics to a public of non-experts. Even for physicists, sometimes it is hard to interpret equations without such aids. Pauline Gagnon has mastered how to explain particle physics to the general public, as she shows in this book full of illustrations but without lack of rigour. She was a senior research scientist at CERN, working with the ATLAS collaboration, until her retirement this year (although she is very active in outreach). Undoubtedly, she knows about particle physics and – more importantly – about its daily practice.

The book is organised into four related areas: particle physics (chapters 1 to 6 and chapter 10), technology spin-offs from particle physics (chapter 7), management in big science (chapter 8) and social issues in the laboratory (chapter 9 on diversity). While the first part was expected, I was positively surprised by the other three. Technology spin-offs are extremely important for society, which in the end is what pays for research. Particle physics is not oriented to economic productivity but driven by a mixture of creativity, perseverance and rigour towards the discovery of how the universe works. On their way to acquiring knowledge, scientists create new tools that can improve our living standards. This book provides a short summary of the technology impact of particle physics in our everyday life and of the effort of CERN to increase the technology spin-off rate by knowledge transfer and workforce training.

Big-science management, especially in the context of a cultural melting pot like CERN, could be very chaotic if it was driven by conventional corporate procedures. The author is clear about this highly non-trivial point: the benefits of the collaborative model we use at CERN in terms of productivity and realising ambitious aims. This organisational model – which she calls the “picnic” model, since each participating institute freely agrees to contribute something – is worth spreading in our modern and interconnected commercial environment, particularly because there are striking similarities with big science when it comes to products and services that are rich in technology and know-how.

As CERN visitors learn, cultural diversity permeates the Organization, and by extension particle physics. Just by taking a seat in any of the CERN restaurants, they can understand that particle physics is a collective and international effort. But they can also easily verify that there is an overwhelming gender imbalance in favour of men. The author, as a woman, addresses the topic of the gender gap in physics and specifically at CERN. She explains why diversity issues, in their overall complexity (not restricted to gender), are very important: our world desperately needs real examples of peaceful and fruitful co-operation between different people with common goals, without gender or cultural barriers.

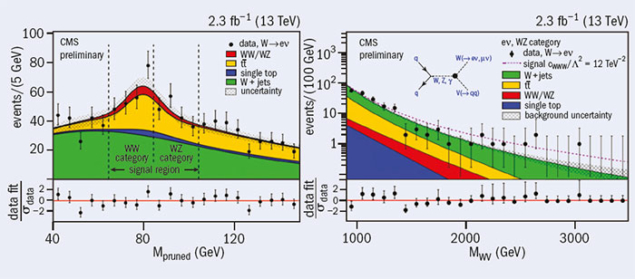

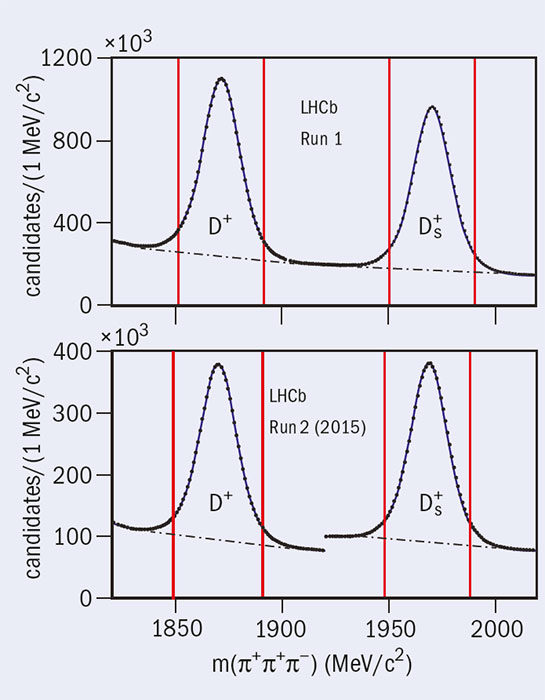

For what concerns the main part of the book, which is focused on contemporary particle physics, chapters 1, 2, 3 and 6 are undoubtedly very well written, in the overall spirit of explaining things easily but nevertheless with full scientific thoroughness. But I was really impressed by chapter 4, on the experimental discovery of the Higgs boson, and 5, on dark matter, mainly because of the firsthand knowledge they reveal. When you read Gagnon’s words you can feel the emotions of the protagonists during that tipping point in modern particle physics. Chapter 5 is an excursion to the dark universe, with wonderful explanations (such as the imaginative comparison between the Bullet Cluster and an American football match). The science in this chapter is up to date and combines particle physics and observational cosmology without apparent effort.

I recommend this book for the general public interested in particle physics but also for particle physicists who want to take a refreshing and general look at the field, even if only to find images to explain physics to family and friends. Because, in the end, everybody cares about particle physics, if you can raise their interest.