Einstein’s long path towards general relativity (GR) began in 1907, just two years after he created special relativity (SR), when the following apparently trivial idea occurred to him: “If a person falls freely, he will not feel his own weight.” Although it was long known that all bodies fall in the same way in a gravitational field, Einstein raised this thought to the level of a postulate: the equivalence principle, which states that there is complete physical equivalence between a homogeneous gravitational field and an accelerated reference frame. After eight years of hard work and deep thinking, in November 1915 he succeeded in extracting from this postulate a revolutionary theory of space, time and gravity. In GR, our best description of gravity, space–time ceases to be an absolute, non-dynamical framework as envisaged by the Newtonian view, and instead becomes a dynamical structure that is deformed by the presence of mass-energy.

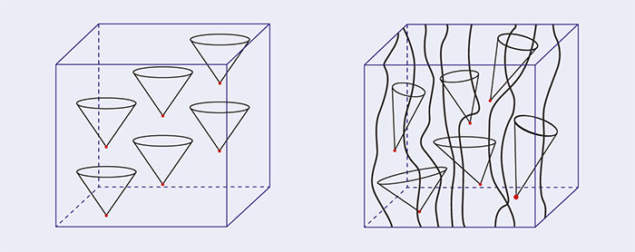

GR has led to profound new predictions and insights that underpin modern astrophysics and cosmology, and which also play a central role in attempts to unify gravity with other interactions. By contrast to GR, our current description of the fundamental constituents of matter and of their non-gravitational interactions – the Standard Model (SM) – is given by a quantum theory of interacting particles of spins 0, ½ and 1 that evolve within the fixed, non-dynamical Minkowski space–time of SR. The contrast between the homogeneous, rigid and matter-independent space–time of SR and the inhomogeneous, matter-deformed space–time of GR is illustrated in figure 1.

The universality of the coupling of gravity to matter (which is the most general form of the equivalence principle) has many observable consequences such as: constancy of the physical constants; local isotropy of space; local Lorentz invariance; universality of free fall and universality of gravitational redshift. Many of these have been verified to high accuracy. For instance, the universality of the acceleration of free fall has been verified on Earth at the 10–13 level, while the local isotropy of space has been verified at the 10–22 level. Einstein’s field equations (see panel below) also predict many specific deviations from Newtonian gravity that can be tested in the weak-field, quasi-stationary regime appropriate to experiments performed in the solar system. Two of these tests – Mercury’s perihelion advance, and light deflection by the Sun – were successfully performed, although with limited precision, soon after the discovery of GR. Since then, many high-precision tests of such post-Newtonian gravity have been performed in the solar system, and GR has passed each of them with flying colours.

Precision tests

Similar to what is done in precision electroweak experiments, it is useful to quantify the significance of precision gravitational experiments by parameterising plausible deviations from GR. The simplest, and most conservative, deviation from Einstein’s pure spin-2 theory is defined by adding a long-range (massless) spin-0 field, φ, coupled to the trace of the energy-momentum tensor. The most general such theory respecting the universality of gravitational coupling contains an arbitrary function of the scalar field defining the “observable metric” to which the SM matter is minimally and universally coupled.

In the weak-field slow-motion limit, appropriate to describing gravitational experiments in the solar system, the addition of φ modifies Einstein’s predictions only through the appearance of two dimensionless parameters, γ and β. The best current limits on these “post-Einstein” parameters are, respectively, (2.1±2.3) × 10–5 (deduced from the additional Doppler shift experienced by radio-wave beams connecting the Earth to the Cassini spacecraft when they passed near the Sun) and < 7 × 10–5, from a study of the global sensitivity of planetary ephemerides to post-Einstein parameters.

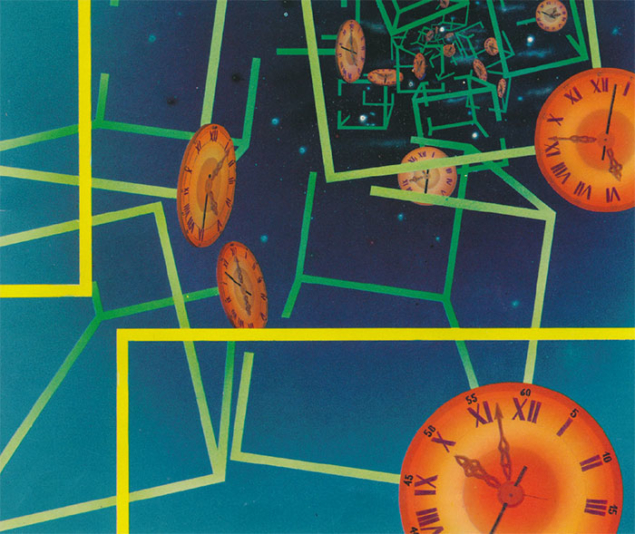

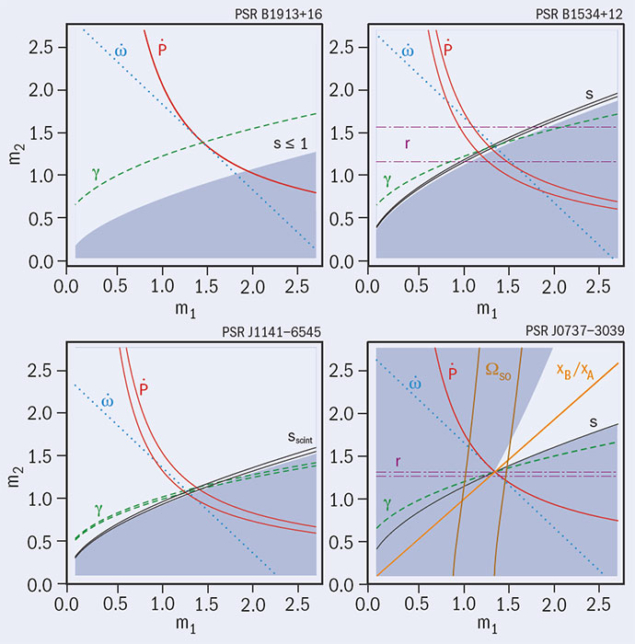

In the regime of radiative and/or strong gravitational fields, by contrast, pulsars (rotating neutron stars emitting a beam of radio waves) in gravitationally bound orbits have provided crucial tests of GR. In particular, measurements of the decay in the orbital period of binary pulsars have provided direct experimental confirmation of the propagation properties of the gravitational field. Theoretical studies of binaries in GR have shown that the finite velocity of propagation of the gravitational interaction between the pulsar and its companion generates damping-like terms at order (v/c)5 in the equations of motion that lead to a small orbital period decay. This has been observed in more than four different systems since the discovery of binary pulsars in 1974, providing direct proof of the reality of gravitational radiation. Measurements of the arrival times of pulsar signals have also allowed precision tests of the quasi-stationary strong-field regime of GR, since their values may depend both on the unknown masses of the binary system and on the theory of gravity used to describe the strong self-gravity of the pulsar and its companion (figure 2).

The radiation revelation

Einstein realised that his field equations had wave-like solutions in two papers in June 1916 and January 1918 (see panel below). For many years, however, the emission of gravitational waves (GWs) by known sources was viewed as being too weak to be of physical significance. In addition, several authors – including Einstein himself – had voiced doubts about the existence of GWs in fully nonlinear GR.

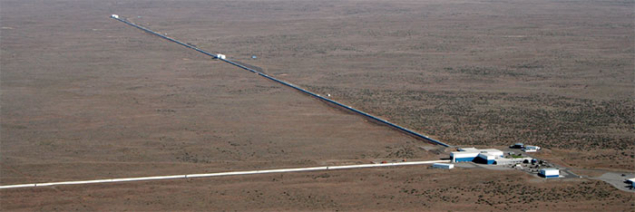

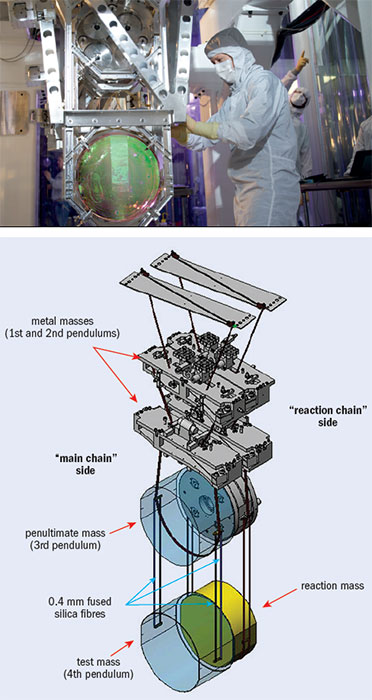

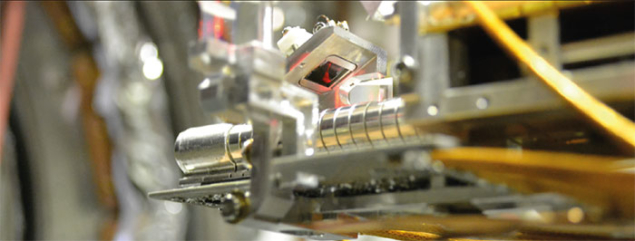

The situation changed in the early 1960s when Joseph Weber understood that GWs arriving on Earth would have observable effects and developed sensitive resonant detectors (“Weber bars”) to search for them. Then, prompted by Weber’s experimental effort, Freeman Dyson realised that, when applying the quadupolar energy-loss formula derived by Einstein to binary systems made of neutron stars, “the loss of energy by gravitational radiation will bring the two stars closer with ever-increasing speed, until in the last second of their lives they plunge together and release a gravitational flash at a frequency of about 200 cycles and of unimaginable intensity.” The vision of Dyson has recently been realised thanks, on the one hand, to the experimental development of drastically more sensitive non-resonant kilometre-scale interferometric detectors and, on the other hand, to theoretical advances that allowed one to predict in advance the accurate shape of the GW signals emitted by coalescing systems of neutron stars and black holes (BHs).

Image credit: MPI/Simulating eXtreme Spacetimes project.

The recent observations of the LIGO interferometers have provided the first detection of GWs in the wave zone. They also provide the first direct evidence of the existence of BHs via the observation of their merger, followed by an abrupt shut-off of the GW signal, in complete accord with the GR predictions.

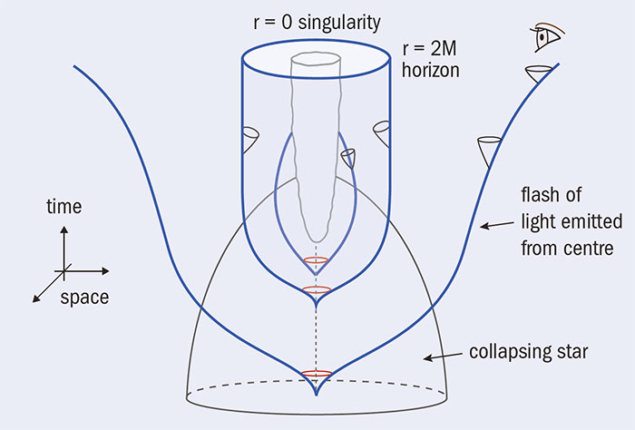

BHs are perhaps the most extraordinary consequence of GR, because of the extreme distortion of space and time that they exhibit. In January 1916, Karl Schwarzschild published the first exact solution of the (vacuum) Einstein equations, supposedly describing the gravitational field of a “mass point” in GR. It took about 50 years to fully grasp the meaning and astrophysical plausibility of these Schwarzschild BHs. Two of the key contributions that led to our current understanding of BHs came from Oppenheimer and Snyder, who in 1939 suggested that a neutron star exceeding its maximum possible mass will undergo gravitational collapse and thereby form a BH, and from Kerr 25 years later, who discovered a generalisation of the Schwarzschild solution describing a BH endowed both with mass and spin.

The Friedmann models still constitute the background models of the current, inhomogeneous cosmologies.

Another remarkable consequence of GR is theoretical cosmology, namely the possibility of describing the kinematics and the dynamics of the whole material universe. The field of relativistic cosmology was ushered in by a 1917 paper by Einstein. Another key contribution was the 1924 paper of Friedmann that described general families of spatially curved, expanding or contracting homogeneous cosmological models. The Friedmann models still constitute the background models of the current, inhomogeneous cosmologies. Quantitative confirmations of GR on cosmological scales have also been obtained, notably through the observation of a variety of gravitational lensing systems.

Dark clouds ahead

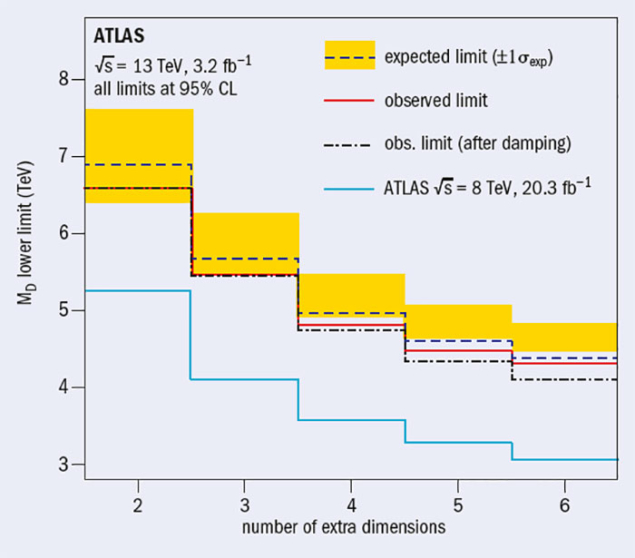

In conclusion, all present experimental gravitational data (universality of free fall, post-Newtonian gravity, radiative and strong-field effects in binary pulsars, GW emission by coalescing BHs and gravitational lensing) have been found to be compatible with the predictions of Einstein’s theory. There are also strong constraints on sub-millimetre modifications of Newtonian gravity from torsion-balance tests of the inverse square law.

One might, however, wish to keep in mind the presence of two dark clouds in our current cosmology, namely the need to assume that most of the stress-energy tensor that has to be put on the right-hand side of the GR field equations to account for the current observations is made of yet unseen types of matter: dark matter and a “cosmological constant”. It has been suggested that these signal a breakdown of Einstein’s gravitation at large scales, although no convincing theoretical modification of GR at large distances has yet been put forward.

GWs, BHs and dynamical cosmological models have become essential elements of our description of the macroscopic universe. The recent and bright beginning of GW astronomy suggests that GR will be an essential tool for discovering new aspects of the universe (see “The dawn of a new era”). A century after its inception, GR has established itself as the standard theoretical description of gravity, with applications ranging from the Global Positioning System and the dynamics of the solar system, to the realm of galaxies and the primordial universe.

However, in addition to the “dark clouds” of dark matter and energy, GR also poses some theoretical challenges. There are both classical challenges (notably the formation of space-like singularities inside BHs), and quantum ones (namely the non-renormalisability of quantum gravity – see “Gravity’s quantum side”). It is probable that a full resolution of these challenges will be reached only through a suitable extension of GR, and possibly through its unification with the current “spin ≤ 1” description of particle physics, as suggested both by supergravity and by superstring theory.

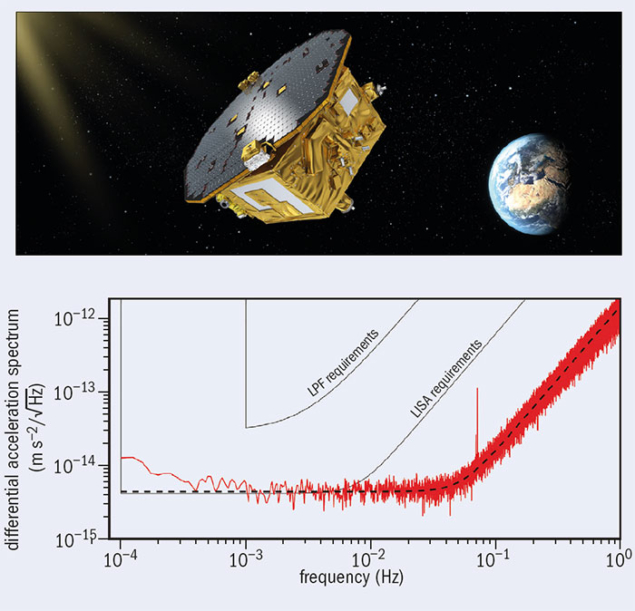

It is therefore vital that we continue to submit GR to experimental tests of increasing precision. The foundational stone of GR, the equivalence principle, is currently being probed in space at the 10–15 level by the MICROSCOPE satellite mission of ONERA and CNES. The observation of a deviation of the universality of free fall would imply that Einstein’s purely geometrical description of gravity needs to be completed by including new long-range fields coupled to bulk matter. Such an experimental clue would be most valuable to indicate the road towards a more encompassing physical theory.

General relativity makes waves

There are two equivalent ways of characterising general relativity (GR). One describes gravity as a universal deformation of the Minkowski metric, which defines a local squared interval between two infinitesimally close space–time points and, consequently, the infinitesimal light cones describing the local propagation of massless particles. The metric field gμν is assumed in GR to be universally and minimally coupled to all the particles of the Standard Model (SM), and to satisfy Einstein’s field equations:

Here, Rμν denotes the Ricci curvature (a nonlinear combination of gμν and of its first and second derivatives), Tμν is the stress-energy tensor of the SM particles (and fields), and G denotes Newton’s gravitational constant.

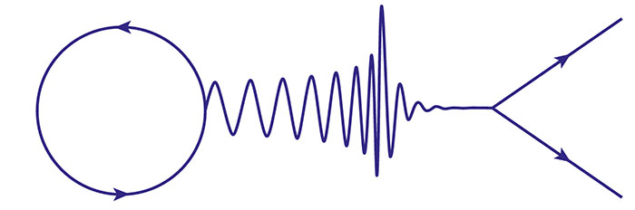

The second way of defining GR, as proven by Richard Feynman, Steven Weinberg, Stanley Deser and others, states that it is the unique, consistent, local, special-relativistic theory of a massless spin-2 field. It is then found that the couplings of the spin-2 field to the SM matter are necessarily equivalent to a universal coupling to a “deformed” space–time metric, and that the propagation and self-couplings of the spin-2 field are necessarily described by Einstein’s equations.

Following the example of Maxwell, who had found that the electromagnetic-field equations admit propagating waves as solutions, Einstein found that the GR field equations admit propagating gravitational waves (GWs). He did so by considering the weak-field limit (gμν = ημν + hμν) of his equations, namely,

where hμν = hμν – ½h ημν. When choosing the co-ordinate system so as to satisfy the gravitational analogue of the Lorenz gauge condition, so that

the linearised field equations simplify to the diagonal inhomogeneous wave equation, which can be solved by retarded potentials.

There are two main results that derive from this wave equation: first, a GW is locally described by a plane wave with two transverse tensorial polarisations (corresponding to the two helicity states of the massless spin-2 graviton) and travelling at the velocity of light; second, a slowly moving, non self-gravitating source predominantly emits a quadupolar GW.