Image credit: CERN.

Superconductivity is a mischievous phenomenon. Countless superconducting materials were discovered following Onnes’ 1911 breakthrough, but none with the right engineering properties. Even today, more than a century later, the basic underlying superconducting material from which magnet coils are made is a bespoke product that has to be developed for specific applications. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity for consumers and producers of superconducting materials.

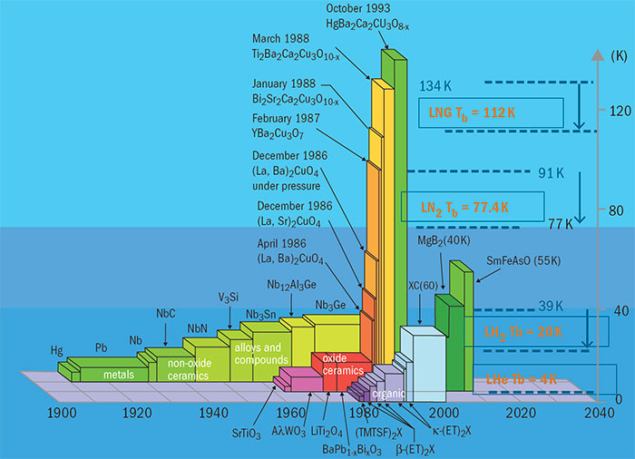

According to trade statistics from 2013, the global market for superconducting products is dominated by the demands of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to the tune of approximately €3.5 bn per year, all of which is based on low-temperature superconductors such as niobium-titanium. Large laboratory facilities make up just under €1 bn of global demand, and there is a hint of a demand for high-temperature superconductors at around €0.3 bn.

Understanding the relationship between industry and big science, in particular large particle accelerators, is vital for such projects to succeed. When the first superconducting accelerator – the Tevatron proton–antiproton collider at Fermilab in the US, employing 774 dipole magnets to bend the beams and 216 quadrupoles to focus them – was constructed in the early 1980s, it is said to have consumed somewhere between 80–90% of all the niobium-titanium superconductor ever made. CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), by far the largest superconducting device ever built, also had a significant impact on industry: its construction in the early 2000s doubled the world output of niobium-titanium for a period of five to six years. The learning curve of high-field superconducting magnet production has been one of the core drivers of progress in high-energy physics (HEP) for the past few decades, and future collider projects are going to test the HEP–industry model to its limits.

The first manufacturers

About a month after the publication of the Bell Laboratories work on high-field superconductivity at the end of January 1961 describing the properties of niobium-tin, it was realised that the experimental conductor – despite being a very small coil consisting of merely a few centimetres of wire – could, with a lot of imagination, be described as an engineering material. The discovery catalysed research into other superconducting metallic alloys and compounds. Just four years later, in 1965, Avco-Everett in co-operation with 14 other companies built a 10 foot, 4 T superconducting magnet using a niobium-zirconium conductor embedded in a copper strip.

Image credit: Siemens.

By the end of 1966, an improved material consisting of niobium-titanium was offered at $9 per foot bare and $13 when insulated. That same year, RCA also announced with great fanfare its entry into commercial high-field superconducting magnet manufacture using the newly developed niobium-tin “Vapodep” ribbon at $4.40 per metre. General Electric was not far behind, offering unvarnished “22CY030” tape at $2.90 per foot in quantities up to 10,000 feet. Kawecki Chemical Company, now Kawecki-Berylco, advertised “superconductive columbium-tin tape in an economical, usable form” in varied widths and minimum unit lengths of 200 m, while in Europe the former French firm CSF marketed the Kawecki product. In the US, Airco claimed the “Kryoconductor” to be pioneering the development of multi-strand fine-filament superconductors for use primarily in low- or medium-field superconducting magnets. Intermagnetics General (IGC) and Supercon were the two other companies with resources adequate to fulfil reasonably sized orders, the latter in particular providing 47,800 kg of copper-clad niobium-titanium conductor for the Argonne National Laboratory’s 12 foot-diameter hydrogen bubble chamber. The industrialisation of superconductor production was in full swing.

Niobium-tin in tape form was the first true engineering superconducting material, and was extensively used by the research community to build and experiment with superconducting magnets. With adequate funds, it was even possible to purchase a magnet built to one’s specifications. One interesting application, which did not see the light of day until many years later, was the use of superconducting tape to exclude magnetic fields from those regions in a beamline through which particle beams had to pass undeviated. As a footnote to this exciting period, in 1962 Martin Wood and his wife founded Oxford Instruments, and four years later delivered the first nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy system. In November last year, the firm sold its superconducting wire business to Bruker Energy and Supercon Technologies, a subsidiary of Bruker Corporation, for $17.5 m.

Beginning of a new industry

One might trace the beginning of the superconducting-magnet revolution to a five-week-long “summer study” at Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1968. Bringing the who’s who in the world of superconductivity together resulted not only in a burst of understanding of the many failures experienced in prior years by magnet builders, but also a deeper appreciation of the arcana of superconducting materials. Researchers at Rutherford Laboratory in the UK, in a series of seminal papers, sufficiently explained the underlying properties and proposed a collaboration with the laboratories at Karlsruhe and Saclay to develop superconducting accelerator magnets. The GESSS (Group for European Superconducting Synchrotron Studies) was to make the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) at CERN a superconducting machine, and this project was large enough to attract the interest of industry – in particular IMI in England. Although GESSS achieved many advances in filamentary conductors and magnet design, the SPS went ahead as a conventional warm-magnet machine. IMI stopped all wire production, but in the US the number of small wire entrepreneurs grew. Niobium-tin tape products gradually disappeared from the market as this superconductor was deemed to be unsuitable for all magnets and especially for accelerator magnet use.

In 1972 the 400 GeV synchrotron at Fermilab, constructed with standard copper-based magnets, became operational, and almost immediately there were plans for an upgrade – this time with superconducting magnets. This project changed the industrial scale, requiring a major effort from manufacturers. To work around the proprietary alloys and processing techniques developed by strand manufacturers, Fermilab settled on an Nb46.5Ti alloy, which was an arithmetic average of existing commercial alloys. This enabled the lab to save around one year in its project schedule.

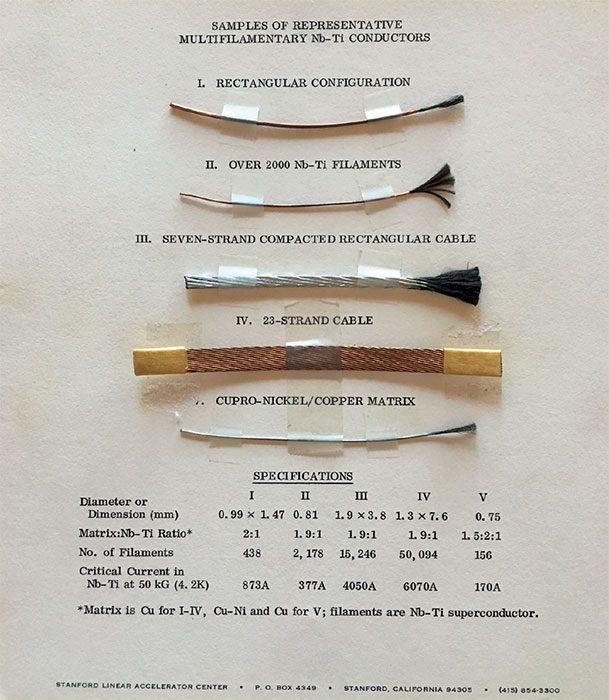

At the same time, the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center was building a large superconducting solenoid for a meson detector, while CERN was undertaking the Big European Bubble Chamber (BEBC) and the Omega Project. This gave industry a reliable view of the future. Numerous large magnets were planned by the various research arms of governments and diverse industry. For example, under the leadership of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory a consortium of six firms constructed a large-scale model of a tokamak reactor magnet assembly using six differently designed coils, each with different superconducting materials: five with niobium-titanium and one with niobium-tin. At the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory work was in progress to develop a tokamak-like fusion device whose coils were again made from niobium-titanium conductor. The US Navy had major plans for electric ship drives, while the Department of Defense was funding the exploration of isotope separation by means of cyclotron resonance, which required superconducting solenoids of substantial size.

Image credit: Steve St Lorant/SLAC.

It appeared that there would be no dearth of succulent orders from the HEP community, with the result that even more companies around the world ventured into the manufacture of superconductors. When the Tevatron was commissioned in 1984, two manufacturers were involved: Intermagnetics General Corporation (IGC) and Magnetic Corporation of America (MCA), in an 80/20 per cent proportion. As is common in particle physics, no sooner had the machine become operational than the need for an upgrade became obvious. However, the planning for such a new larger and more complex device took considerable time, during which the superconductor manufacturers effectively made no sales and hence no profits. This led to the disappearance of less well capitalised companies, unless they had other products to market, as did Supercon and Oxford Instruments. The latter expanded into MRI, and its first prototype MRI magnet built in 1979 became the foundation of a current annual world production that totals around 3500 units. MRI production ramped up as the Tevatron demand declined and the correspondingly large amount of niobium-titanium conductor that it required has been stable since then.

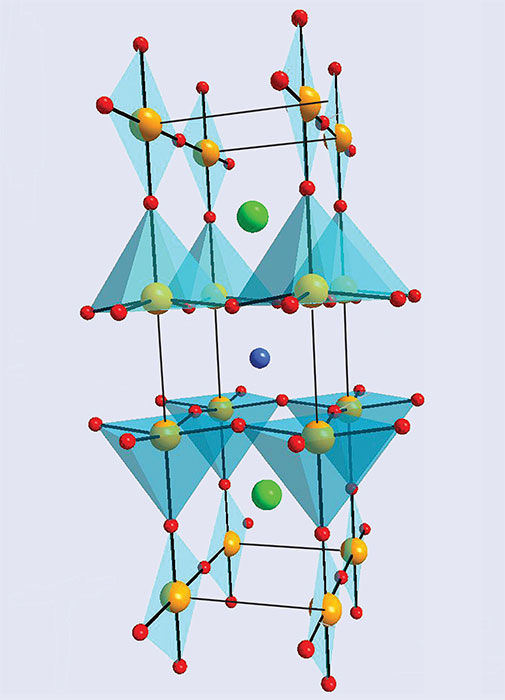

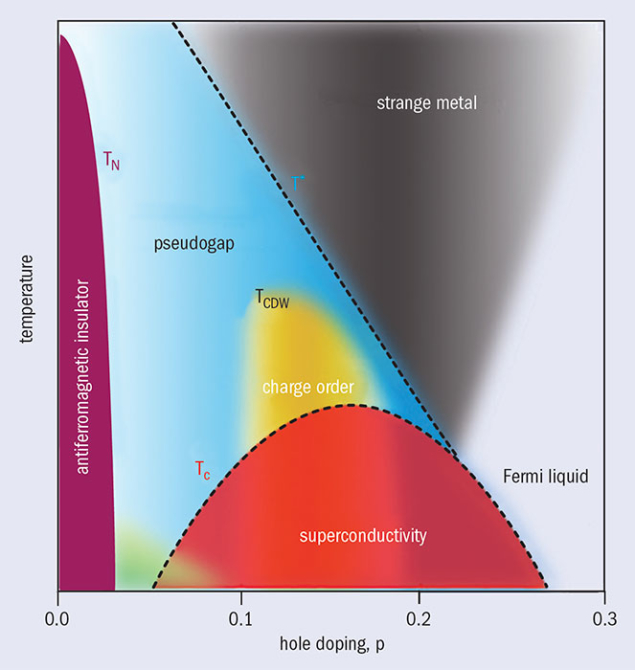

The demise of ISABELLE, a 400 GeV proton–proton collider at Brookhaven, in 1983, and then the Superconducting Super Collider a decade later, resulted in a further retrenchment of the superconductor industry, with a number of pioneering establishments either disappearing or being bought out. The industrial involvement in the construction of the superconducting machines HERA at DESY and RHIC at BNL somewhat alleviated the situation. The discovery of high-temperature superconductivity (HTS) in 1986 also helped, although it is not clear that great profits, if any, have been made so far in the HTS arena.

A cloudy crystal ball

The superconducting wire business in the Western world has undergone significant consolidation in recent years. Niobium-titanium wire is now a commodity with a very low profit margin because it has become a standard, off-the-shelf product used primarily for MRI applications. There are now more companies than the market can support for this conductor, but for HEP and other research applications the market is shifting to its higher-performing cousin: niobium-tin.

Following the completion of the LHC in the early 2000s, the US Department of Energy looked toward the next generation of accelerator magnets. LHC technology had pushed the performance of niobium-titanium to its limits, so investment was directed towards niobium-tin. This conductor was also being developed for the fusion community ITER (“ITER’s massive magnets enter production”), but HEP required a higher performance for use in accelerators. Over a period of a few years, the critical-current performance of niobium-tin almost doubled and the conductor is now a technological basis of the High Luminosity LHC (see “Powering the field forward”). Although this major upgrade is proceeding as planned, as always all eyes are on the next step – perhaps an even larger machine based on even more innovative magnet technology. For example, a 100 TeV proton collider under consideration by the Future Circular Collider study, co-ordinated by CERN, will require global-scale procurement of niobium-tin strands and cable similar in scale to the demands of ITER.

Beyond that, the view of the superconductor industry is into a cloudy crystal ball. The current political and economic environment does not give grounds for hope, at least not in the Western world, that a major superconducting project is to be built in the near future. More generally, other than MRI, the commercial applications of superconductivity have not caught on due to customer impressions of additional complexity and risk against marginal increases in performance. We also have the consequences of the challenges that ITER has faced regarding its costs, which can attract the undeserved opinion that scientists cannot manage large projects.

One facet of the superconductor industry that seems to be thriving is small-venture establishments, sometimes university departments, which carry out superconductor R&D quasi-independently of major industrial concerns. These establishments maintain themselves under various government-sponsored support, such as the SBIR and STTR programmes in the US, and stepwise and without much fanfare they are responsible for the improvement of current superconductors, be they low- or high-temperature. As long as such arrangements are maintained, healthy progress in the science is assured, and these results feed directly to industry. And as far as HEP is concerned, as long as there are beams to guide, bend and focus, we will continue to need manufacturers to make the wires and fabricate the superconducting magnet coils.

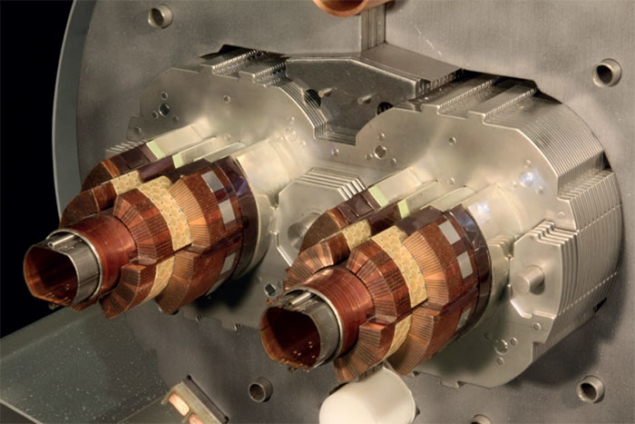

Snapshot: manufacturing the LHC magnets

The production of the niobium-titanium conductor for the LHC’s 1800 or so superconducting magnets was of the highest standard, involving hundreds of individual superconducting strands assembled into a cable that had to be shaped to accommodate the geometry of the magnet coil. Three firms manufactured the 1232 main dipole magnets (each 15 m long and weighing 35 tonnes): the French consortium Alstom MSA–Jeumont Industries; Ansaldo Superconduttori in Italy; and Babcok Noell Nuclear in Germany. For the 400 main quadrupoles, full-length prototyping was developed in the laboratory (CEA–CERN) and the tender assigned to Accel in Germany. Once LHC construction was completed, the superconductor market dropped back to meet the base demands of MRI. There has been a similar experience with the niobium-tin conductor used for the ITER fusion experiment under construction in France: more than six companies worldwide made the strands before the procurement was over, after which demand dropped back to pre-project levels.

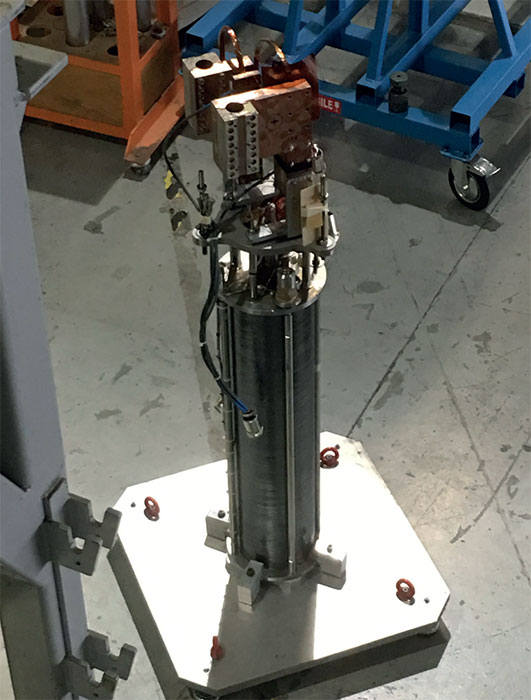

Transforming brittle conductors into high-performance coils at CERN

The manufacture of superconductors for HEP applications is in many ways a standard industrial flow process with specialised steps. The superconductor in round rod form is inserted into copper tubes, which have a round inside and a hexagonal outside perimeter (the image inset shows such a “billet” for the former HERA electron–proton collider at DESY). A number of these units are then stacked into a copper can that is vacuum sealed and extruded in a hydraulic press, and this extrusion is processed on a draw bench where it is progressively reduced in diameter.

The manufacture of superconductors for HEP applications is in many ways a standard industrial flow process with specialised steps. The superconductor in round rod form is inserted into copper tubes, which have a round inside and a hexagonal outside perimeter (the image inset shows such a “billet” for the former HERA electron–proton collider at DESY). A number of these units are then stacked into a copper can that is vacuum sealed and extruded in a hydraulic press, and this extrusion is processed on a draw bench where it is progressively reduced in diameter.

Image credit: CERN.

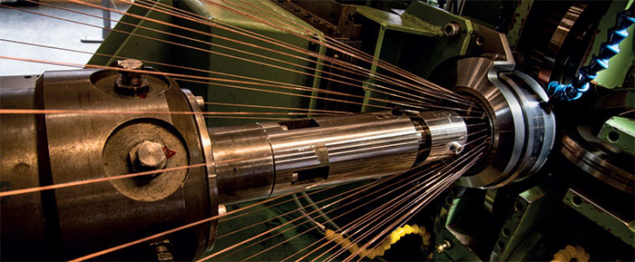

The greatly reduced product is then drawn through a series of dies until the desired wire diameter in reached, and a number of these wires are formed into cables ready for use. The overall process is highly complex and often involves several countries and dozens of specialised industries before the reel of wire or cable arrives at the magnet factory. Each step must ultimately be accounted for and any sudden change to a customer’s source of funds can land the manufacturer with unsaleable stock. Superconductors are specified precisely for their intended end use, and only in rare instances is a stocked product applicable to another application.