The 13th Low Energy Antiproton Physics (LEAP) conference was held from 12–16 March at the Sorbonne University International Conference Center in Paris. A large part of the conference focused on experiments at the CERN Antiproton Decelerator (AD), in particular the outstanding results recently obtained by ALPHA and BASE.

One of the main goals of this field is to explain the lack of antimatter observed in the present universe, which demands that physicists look for any difference between matter and antimatter, apart from their quantum numbers. Specifically, experiments at the AD make ultra-precise measurements to test charge-party-time (CPT) invariance and soon, via the free-fall of antihydrogen atoms, the gravitational equivalence principle to look for any differences between matter and antimatter that would point to new physics.

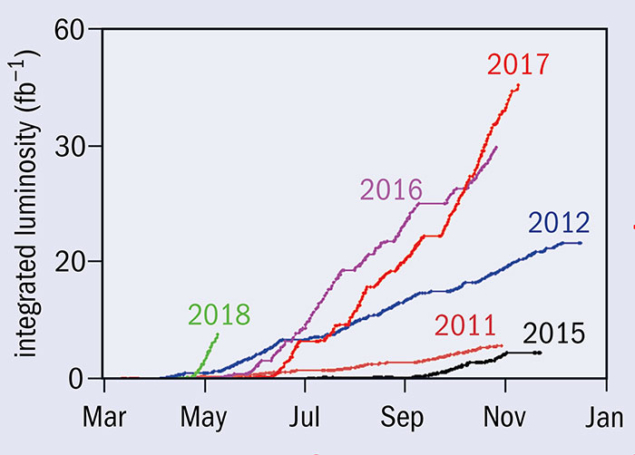

The March meeting began with talks about antimatter in space. AMS-02 results, based on a sample of 3.49 × 105 antiprotons detected during the past four years onboard the International Space Station, showed that antiprotons, protons and positrons have the same rigidity spectrum in the energy range 60–500 GeV. This is not expected in the case of pure secondary production and could be a hint of dark-matter interactions (CERN Courier December 2016 p31). The development of facilities at the AD, including the new ELENA facility, and at the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research Facility (FAIR), were also described. FAIR, under construction in Darmstadt, Germany, will increase the antiproton flux by at least a factor of 10 compared to ELENA and allow new physics studies focusing, for example, on the interactions between antimatter and radioactive beams (CERN Courier July/August 2017 p41).

Talks covering experimental results and the theory of antiproton interactions with matter, and the study of the physics of antihydrogen, were complemented with discussions on other types of antimatter systems, such as purely leptonic positronium and muonium. Measurements of these systems offer tests of CPT in a different sector, but their short-lived nature could make experiments here even more challenging than those on antihydrogen.

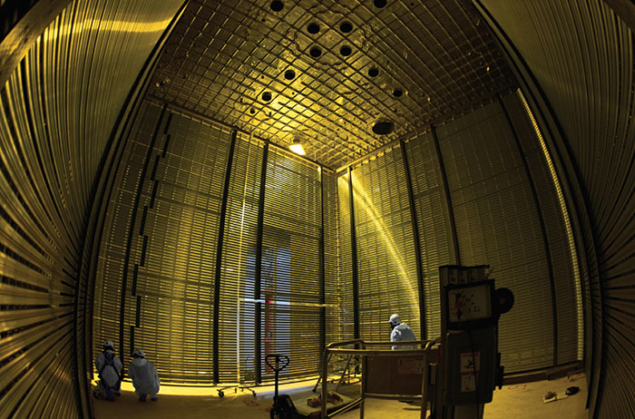

Stefan Ulmer and Christian Smorra from the AD’s BASE experiment described how they managed to keep antiprotons in a magnetic trap for more than 400 days under an astonishingly low pressure of 5 × 10–19 mbar. There is no gauge to measure such a value, only the lifetime of antiprotons and the probability of annihilation with residual gas in the trap. The feat allowed the team to set the best direct limit so far on the lifetime of the antiproton: 21.7 years (indirect observations from astrophysics indicate an antiproton lifetime in the megayear range). The BASE measurement of the proton-to-antiproton charge over mass ratio (CERN Courier September 2015 p7) is consistent with CPT invariance and, with a precision of 0.69 × 10–12, it is the most stringent test of CPT with baryons. The BASE comparison of the magnetic moment of the proton and the antiproton at the level of 2 × 10–10 is another impressive achievement and is also consistent with CPT (CERN Courier March 2017 p7).

Three new results from ALPHA, which has now achieved stable operation in the manipulation of antihydrogen atoms that has allowed spectroscopy to be performed on 15,000 antiatoms, were also presented. Tim Friesen presented the hyperfine spectrum and Takamasa Momose presented the spectroscopy of the 1S–2P transition. Chris Rasmussen presented the 1S–2S lineshape, which gives a resonant frequency consistent with that of hydrogen at a precision of 2 × 10–12 or an energy level of 2 × 10–20 GeV, already exceeding the precision on the mass difference between neutral kaons and antikaons. ALPHA’s rapid progress suggests hydrogen- like precision in antihydrogen is achievable, opening unprecedented tests of CPT symmetry (CERN Courier March 2018 p30).

The next edition of the LEAP conference will take place at Berkeley in the US in August 2020. Given the recent pace of research in this relatively new field of fundamental exploration, we can look forward to a wealth of new results between now and then.