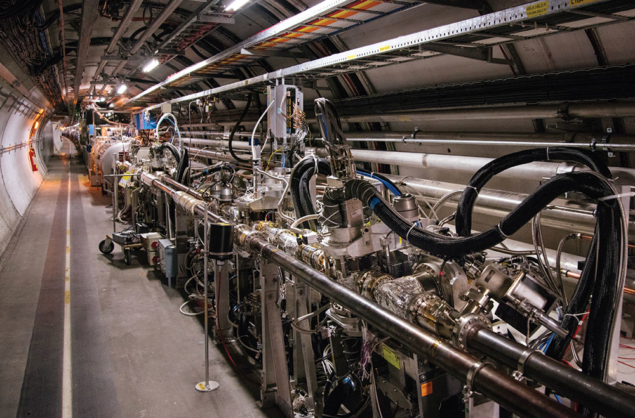

The High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC), scheduled to operate from 2026, will increase the instantaneous luminosity of the LHC by at least a factor of five beyond its initial design luminosity. The analysis of a fraction of the data already delivered by the LHC – a mere 6% of what is expected by the end of HL-LHC in the late-2030s – led to the discovery of the Higgs boson and a diverse set of measurements and searches that have been documented in some 2000 physics papers published by the LHC experiments. “Although the HL-LHC is an approved and funded project, its physics programme evolves with scientific developments and also with the physics programmes planned at future colliders,” says Aleandro Nisati of ATLAS, who is a member of the steering group for a new report quantifying the HL-LHC physics potential.

The 1000+ page report, published in January, contains input from more than 1000 experts from the experimental and theory communities. It stems from an initial workshop at CERN held in late 2017 (CERN Courier January/February 2018 p44) and also addresses the physics opportunities at a proposed high-energy upgrade (HE-LHC). Working groups have carried out hundreds of projections for physics measurements within the extremely challenging HL-LHC collision environment, taking into account the expected evolution of the theoretical landscape in the years ahead. In addition to their experience with LHC data analysis, the report factors in the improvements expected from the newly upgraded detectors and the likelihood that new analysis techniques will be developed. “A key aspect of this report is the involvement of the whole LHC community, working closely together to ensure optimal scientific progress,” says theorist and steering-group member Michelangelo Mangano.

Physics streams

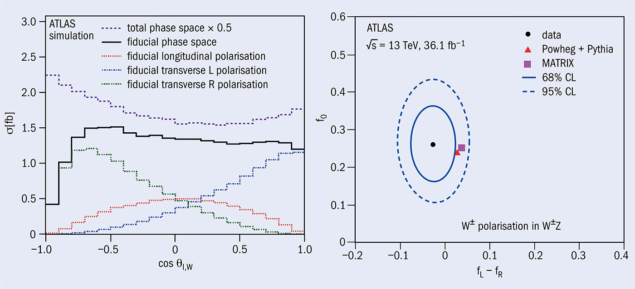

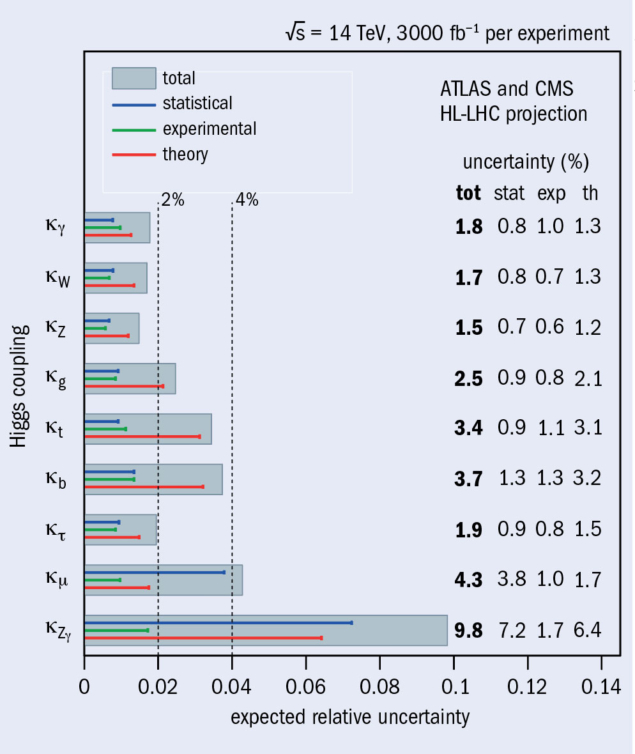

The physics programme has been distilled into five streams: Standard Model (SM), Higgs, beyond the SM, flavour and QCD matter at high density. The LHC results so far have confirmed the validity of the SM up to unprecedented energy scales and with great precision in the strong, electroweak and flavour sectors. Thanks to a 10-fold larger data set, the HL-LHC will probe the SM with even greater precision, give access to previously unseen rare processes, and will extend the experiments’ sensitivity to new physics in direct and indirect searches for processes with low-production cross sections and more elusive signatures. The precision of key measurements, such as the coupling of the Higgs boson to SM particles, is expected to reach the percent level, where effects of new physics could be seen. The experimental uncertainty on the top-quark mass will be reduced to a few hundred MeV, and vector-boson scattering – recently observed in LHC data – will be studied with an accuracy of a few percent using various diboson processes.

The 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson opens brand-new studies of its properties, the SM in general, and of possible physics beyond the SM. Outstanding opportunities have emerged for measurements of fundamental importance at the HL-LHC, such as the first direct constraints on the Higgs trilinear self-coupling and the natural width. The experience of LHC Run 2 has led to an improved understanding of the HL-LHC’s ability to probe Higgs pair production, a key measure of its self-interaction, with a projected combined ATLAS and CMS sensitivity of four standard deviations. In addition to significant improvements on the precision of Higgs-boson measurements (figure 1), the HL-LHC will improve searches for heavier Higgs bosons motivated by theories beyond the SM and will be able to probe very rare exotic decay modes thanks to the huge dataset expected.

The new report considers a large variety of new-physics models that can be probed at HL-LHC. In addition to searches for new heavy resonances and supersymmetry models, it includes results on dark matter and dark sectors, long-lived particles, leptoquarks, sterile neutrinos, axion-like particles, heavy scalars, vector-like quarks, and more. “Particular attention is placed on the potential opened by the LHC detector upgrades, the assessment of future systematic uncertainties, and new experimental techniques,” says steering-group member Andreas Meyer of CMS. “In addition to extending the present LHC mass and coupling reach by 20–50% for most new-physics scenarios, the HL-LHC will be able to potentially discover, or constrain, new physics that is not in reach of the current LHC dataset.”

Pushing for precision

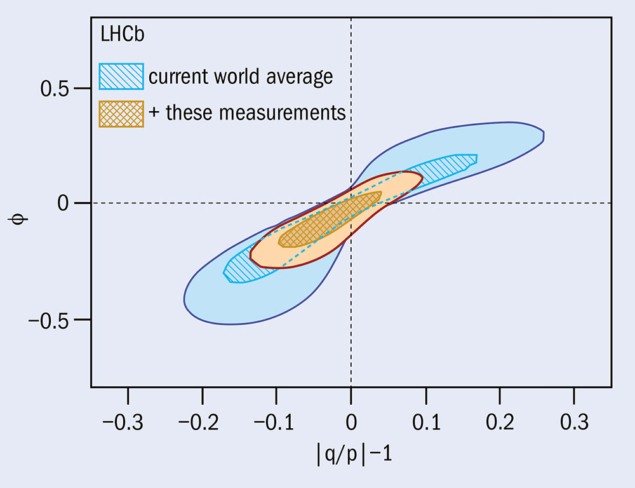

The flavour-physics programme at the HL-LHC comprises many different probes – the weak decays of beauty, charm, strange and top quarks, as well as of the τ lepton and the Higgs boson – in which the experiments can search for signs of new physics. ATLAS and CMS will push the measurement precision of Higgs couplings and search for rare top decays, while the proposed second phase of the LHCb upgrade will greatly enhance the sensitivity with a range of beauty-, charm-, and strange-hadron probes. “It’s really exciting to see the full potential of the HL-LHC as a facility for precision flavour physics,” says steering-group member Mika Vesterinen of LHCb. “The projected experimental advances are also expected to be accompanied by improvements in theory, enhancing the current mass-reach on new physics by a factor as large as four.”

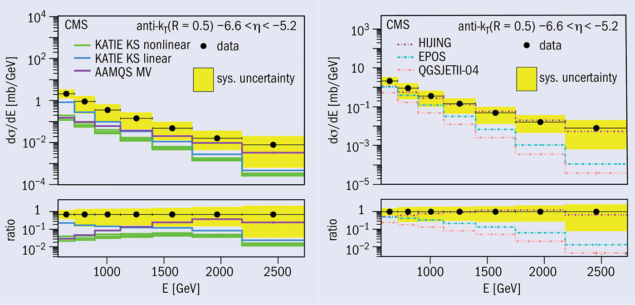

Finally, the report identifies four major scientific goals for future high-density QCD studies at the LHC, including detailed characterisation of the quark–gluon plasma and its underlying parton dynamics, the development of a unified picture of particle production, and QCD dynamics from small to large systems. To address these goals, high-luminosity lead–lead and proton–lead collision programmes are considered as priorities, while high-luminosity runs with intermediate-mass nuclei such as argon could extend the heavy-ion programme at the LHC into the HL-LHC phase.

High-energy considerations

One of the proposed options for a future collider at CERN is the HE-LHC, which would occupy the same tunnel but be built from advanced high-field dipole magnets that could support roughly double the LHC’s energy. Such a machine would be expected to deliver an integrated proton–proton luminosity of 15,000 fb–1 at a centre-of-mass energy of 27 TeV, increasing the discovery mass-reach beyond anything possible at the HL-LHC. The HE-LHC would provide precision access to rare Higgs boson (H) production modes, with approximately a 2% uncertainty on the ttH coupling, as well as an unambiguous observation of the HH signal and a precision of about 20% on the trilinear coupling. An HE-LHC would enable a heavy new Z´ gauge boson discovered at the HL-LHC to be studied in detail, and in general double the discovery reach of the HL-LHC to beyond 10 TeV.

The HL/HE-LHC reports were submitted to the European Strategy for Particle Physics Update in December 2018, and are also intended to bring perspective to the physics potential of future projects beyond the LHC. “We now have a better sense of our potential to characterise the Higgs boson, hunt for new particles and make Standard Model measurements that restrict the opportunities for new physics to hide,” says Mangano. “This report has made it clear that these planned 3000 fb–1 of data from HL-LHC, and much more in the case of a future HE-LHC, will play a central role in particle physics for decades to come.”