In 1971, at a Baskin-Robbins ice-cream store in Pasadena, California, Murray Gell-Mann and his student Harald Fritzsch came up with the term “flavour” to describe the different types of quarks. From the three types known at the time – up, down and strange – the list of quark flavours grew to six. A similar picture evolved for the leptons: the electron and the muon were joined by the unexpected discovery of the tau lepton at SLAC in 1975 and completed with the three corresponding neutrinos. These 12 elementary fermions are grouped into three generations of increasing mass.

The three flavours of charged leptons – electron, muon and tau – are the same in many respects. This “flavour universality” is deeply ingrained in the symmetry structure of the Standard Model (SM) and applies to both the electroweak and strong forces (though the latter is irrelevant for leptons). It directly follows from the assumption that the SM gauge group, SU(3) × SU(2) × U(1), is one and the same for all three generations of fermions. The Higgs field, on the other hand, distinguishes between fermions of different flavours and endows them with different masses – sometimes strikingly so. In other words, the gauge forces, such as the electroweak force, are flavour-universal in the SM, while the exchange of a Higgs particle is not.

Today, flavour physics is a major field of activity. A quick look at the Particle Data Group (PDG) booklet, with its long lists of the decays of B mesons, D mesons, kaons and other hadrons, gives an impression of the breadth and depth of the field. Even in the condensed version of the PDG booklet, such listings run to more than 170 pages. Still, the results can be summarised succinctly: all the measured decays agree with SM predictions, with the exception of measurements that probe LFU in two quark-level transitions: b → cτ–ν̅τ and b → sμ+μ–.

Oddities in decays to D mesons

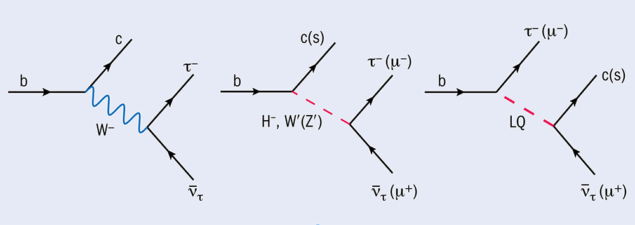

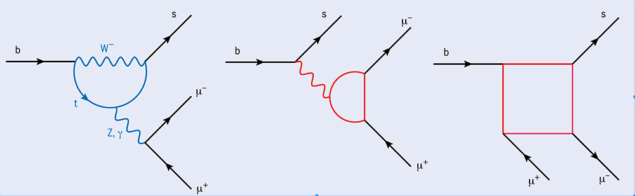

In the SM the b → cτ–ν̅τ process is due to a tree-level exchange of a virtual W boson (figure 1, left). The W boson, being much heavier than the amount of energy that is released in the decay of the b quark, is virtual. Rather than materialising as a particle, it leaves its imprint as a very short-range potential that has the property of changing one quark (a b quark) into a different one (a c quark) with the simultaneous emission of a charged lepton and an antineutrino.

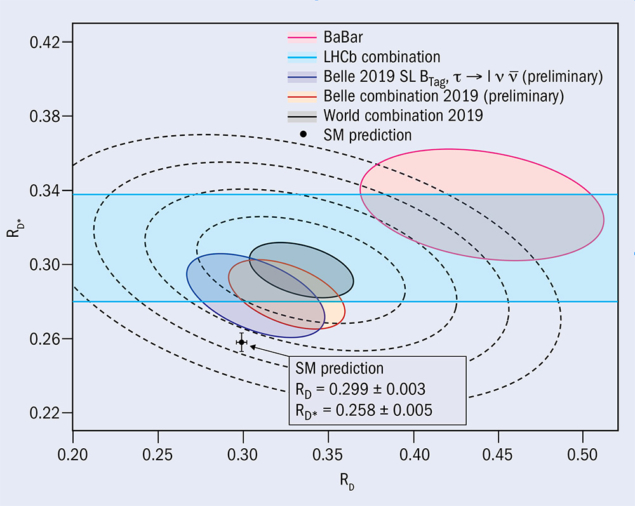

Flavour universality is probed by measuring the ratio of branching fractions: RD(*) = Br(B → D(*)τ–ν̅τ)/Br(B → D(*)l–ν̅l), where l = e, μ. Two ratios can be measured, since the charm quark is either bound inside a D meson or its excited version, the D*, and the two ratios, RD and RD*, have the very welcome property that they can be precisely predicted in the SM. Importantly, since the hadronic inputs that describe the b → c transition do not depend on which lepton flavour is in the final state, the induced uncertainties mostly cancel in the ratios. Currently, the SM prediction is roughly three standard deviations away from the global average of results from the LHCb, BaBar and Belle experiments (figure 2).

A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that there is an additional contribution to the decay rate, due to the exchange of a new virtual particle. For coupling strengths that are of order unity, such that they are appreciably large yet small enough to keep our calculations reliable, the mass of such a new particle needs to be about 3 TeV to explain the reported hints for the increased b → cτ–ν̅τ rates. This is light enough that the new particle could even be produced directly at the LHC. Even better, the options for what this new particle could be are quite restricted.

There are two main possibilities. One is a colour singlet that does not feel the strong force, for which candidates include a new charged Higgs boson or a new vector boson commonly denoted W′ (figure 1, middle). However, both of these options are essentially excluded by other measurements that do agree with the SM: the lifetime of the Bc meson; searches at the LHC for anomalous signals with tau leptons in the final state; decays of weak W and Z bosons into leptons; and by Bs mixing and B → Kν ν̅ decays.

The second possible type of new particle is a leptoquark that couples to one quark and one lepton at each vertex (figure 3, right). Typically, the constraints from other measurements are less severe for leptoquarks than they are for new colour-singlet bosons, making them the preferred explanation for the b → cτ–ν̅τ anomaly. For instance, they contribute to Bs mixing at the one-loop level, making the resulting effect smaller than the present uncertainties. Since leptoquarks are charged under the strong force, in the same way as quarks are, they can be copiously produced at the LHC via strong interactions. Searches for pair- or singly-produced leptoquarks at the future high-luminosity LHC and at a proposed high-energy LHC will cover most of the available parameter space of current models.

Oddities in decays to kaons

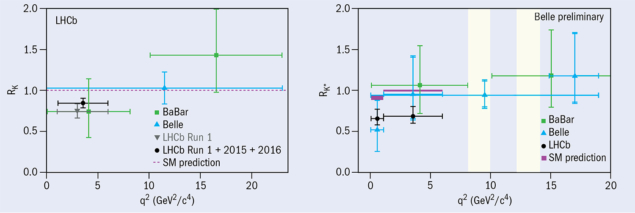

The other decay showing interesting flavour deviations (b → sμ+μ–) is probed via the ratios RK(*) = Br(B → K(*)μ+μ–)/Br(B → K(*)e+e–), which test whether the rate for the b → sμ+μ– quark-level transition equals the rate for the b → se+e– one. The SM very precisely predicts RK(*) = 1, up to small corrections due to the very different masses of the muon and the electron. Measurements from LHCb on the other hand, are consistently below 1, with statistical significances of about 2.5 standard deviations, while less precise measurements from Belle are consistent with both LHCb and the SM (figure 3). Further support for these discrepancies is obtained from other observables, for which theoretical predictions are more uncertain. These include the branching ratios for decays induced by the b → sμ+μ– quark-level transition, and the distributions of the final-state particles.

In contrast to the tree-level b → cτ–ν̅τ process underlying the semileptonic B decays to D mesons, the b → sμ+μ– decay is induced via quantum corrections at the one-loop level (figure 4, left) and is therefore highly suppressed in the SM. Potential new-physics contributions, on the other hand, can be exchanged either at tree level or also at one-loop level. This means that there is quite a lot of freedom in what kind of new physics could explain the b → sμ+μ– anomaly. The possible tree-level mediators are a Z′ and leptoquarks with masses of about 30 TeV or lighter, if the couplings are smaller. For loop-induced models the new particles are necessarily light, with masses in the TeV range or below. This means that the searches for direct production of new particles at the LHC can probe a significant range of explanations for the LHCb anomalies. However, for many of the possibilities the high-energy upgrade to the LHC or a future circular collider with much higher energy would be required for the new particles to be discovered or ruled out.

Taking stock

Could the two anomalies be due to a single new lepton non-universal force? Interestingly, a leptoquark dubbed U1 – a spin-one particle that is a colour triplet, charged under hypercharge but not weak isospin – can explain both anomalies. With some effort it can be embedded in consistent theoretical constructions, albeit those with very non-trivial flavour structures. These models are based on modified versions of grand unified theories (GUTs) from the 1980s. Since GUTs unify the leptons and quarks, some of the force carriers can change quarks to leptons and vice versa, i.e. some of the force carriers are leptoquarks. The U1 leptoquark could be one such force carrier, coupling predominantly to the third generation of fermions. In all cases the U1 leptoquark is accompanied by many other particles with masses not much above the mass of U1.

While intriguing, the two sets of B-physics anomalies are by no means confirmed. None of the measurements have separately reached the five standard deviations needed to claim a discovery and, indeed, most are hovering around the 1–3 sigma mark. However, taken together, they form an interesting and consistent picture that something is potentially going on. We are in a lucky position that new measurements are expected to be finished soon, some in a few months, others in a few years.

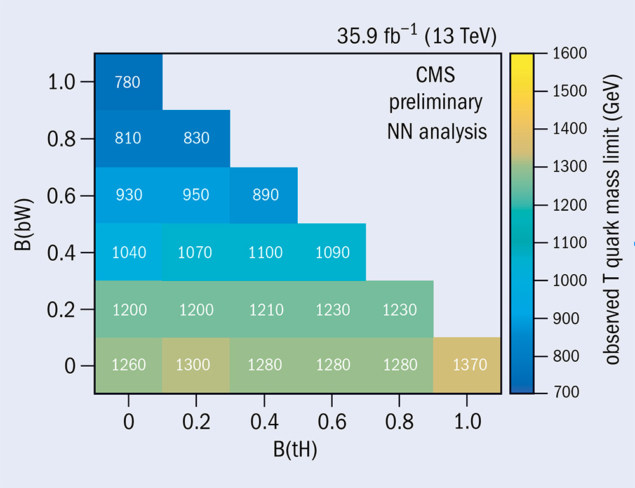

First of all, the observables showing the discrepancy from the SM, RD(*) and RK(*), will be measured more precisely at LHCb and at Belle II, which is currently ramping up at KEK in Japan. In addition, there are many related measurements that are planned, both at Belle II as well as at LHCb, and also at ATLAS and CMS. For instance, measuring the same transitions, but with different initial- and final-state hadrons, should give further insights into the structure of new-physics contributions. If the anomalies are confirmed, this would then set a clear target for the next collider such as the high-energy LHC or the proposed proton–proton Future Circular Collider, since the new particles cannot be arbitrarily heavy.

If this exciting scenario plays out, it would not be the first time that indirect searches foretold the existence of new physics at the next energy scale. Nuclear beta decay and other weak transitions prognosticated the electroweak W and Z gauge bosons, the rare kaon decay KL → μ+μ– pointed to the existence of the charm quark, including the prediction for its mass from kaon mixing, while B-meson mixings and measurements of electroweak corrections accurately predicted the top-quark mass before it was discovered. Finally, the measurement of CP violation in kaons led to the prediction of the third generation of fermions. If the present flavour anomalies stand firm, they will become another important item on this historic list, offering a view of a new energy scale to explore.