High-energy particle colliders have proved to be indispensable tools in the investigation of the nature of the fundamental forces. The LHC, at which the discovery of the Higgs boson was made in 2012, is a prime recent example. Several major projects have been proposed to push our understanding of the universe once the LHC reaches the end of its operations in the late 2030s. These have been the focus of discussions for the soon-to-conclude update of the European strategy for particle physics. An electron–positron Higgs factory that allows precision measurements of the Higgs boson’s couplings and the Higgs potential seems to have garnered consensus as the best machine for the near future. The question is: what type will it be?

Today, mature options for electron–positron colliders exist: the Future Circular Collider (FCC-ee) and the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC) proposals at CERN; the International Linear Collider (ILC) in Japan; and the Circular Electron–Positron Collider (CEPC) in China. FCC-ee offers very high luminosities at the required centre-of-mass energies. However, the maximum energy that can be reached is limited by the emission of synchrotron radiation in the collider ring, and corresponds to a centre-of-mass energy of 365 GeV for a 100 km-circumference machine. Linear colliders accelerate particles without the emission of synchrotron radiation, and hence can reach higher energies. The ILC would initially operate at 250 GeV, extendable to 1 TeV, while the highest energy proposal, CLIC, has been designed to reach 3 TeV. However, there are two principal challenges that must be overcome to go to higher energies with a linear machine: first, the beam has to be accelerated to full energy in a single passage through the main linac; and, second, it can only be used once in a single collision. At higher energies the linac has to be longer (around 50 km for a 1 TeV ILC and a 3 TeV CLIC) and is therefore more costly, while the single collision of the beam also limits the luminosity that can be achieved for a reasonable power consumption.

Beating the lifetime

An ingenious solution to overcome these issues is to replace the electrons and positrons with muons and anti-muons. In a muon collider, fundamental particles that are not constituents of ordinary matter would collide for the first time. Being 200 times heavier than the electron, the muon emits about two billion times less synchrotron radiation. Rings can therefore be used to accelerate muon beams efficiently and to bring them into collision repeatedly. Also, more than one experiment can be served simultaneously to increase the amount of data collected. Provided the technology can be mastered, it appears possible to reach a ratio of luminosity to beam power that increases with energy. The catch is that muons live on average for 2.2 μs, which leads to a reduction in the number of muons produced by about an order of magnitude before they enter the storage ring. One therefore has to be rather quick in producing, accelerating and colliding the muons; this rapid handling provides the main challenges of such a project.

Precision and discovery

The development of a muon collider is not as advanced as the other lepton-collider options that were submitted to the European strategy process. Therefore the unique potential of a multi-TeV muon collider deserves a strong commitment to fully demonstrate its feasibility. Extensive studies submitted to the strategy update show that a muon collider in the multi-TeV energy range would be competitive both as a precision and as a discovery machine, and that a full effort by the community could demonstrate that a muon collider operating at a few TeV can be ready on a time scale of about 20 years. While the full physics capabilities at high energies remain to be quantified, and provided the beam energy and detector resolutions at a muon collider can be maintained at the parts-per-mille level, the number of Higgs bosons produced would allow the Higgs’ couplings to fermions and bosons to be measured with extraordinary precision. A muon collider operating at lower energies, such as those for the proposed FCC-ee (250 and 365 GeV) or stage-one CLIC (380 GeV) machines, has not been studied in detail since the beam-induced background will be harsher and careful optimisation of machine parameters would be required to reach the needed luminosity. Moreover, a muon collider generating a centre-of-mass energy of 10 TeV or more and with a luminosity of the order of 1035 cm–2 s–1 would allow a direct measurement of the trilinear and quadrilinear self-couplings of the Higgs boson, enabling a precise determination of the shape of the Higgs potential. While the precision on Higgs measurements achievable at muon colliders is not yet sufficiently evaluated to perform a comparison to other future colliders, theorists have recently shown that a muon collider is competitive in measuring the trilinear Higgs coupling and that it could allow a determination of the quartic self-coupling that is significantly better than what is currently considered attainable at other future colliders. Owing to the muon’s greater mass, the coupling of the muon to the Higgs boson is enhanced by a factor of about 104 compared to the electron–Higgs coupling. To exploit this, previous studies have also investigated a muon collider operating at a centre-of-mass energy of 126 GeV (the Higgs pole) to measure the Higgs-boson line-shape. The specifications for such a machine are demanding as it requires knowledge of the beam-energy spread at the level of a few parts in 105.

Half a century of ideas

The idea of a muon collider was first introduced 50 years ago by Gersh Budker and then developed by Alexander Skrinsky and David Neuffer until the Muon Collider Collaboration became a formal entity in 1997, with more than 100 physicists from 20 institutions in the US and a few more from Russia, Japan and Europe. Brookhaven’s Bob Palmer was a key figure in driving the concept forward, leading the outline of a “complete scheme” for a muon collider in 2007. Exploratory work towards a muon collider and neutrino factory was also carried out at CERN around the turn of the millennium. It was only when the Muon Accelerator Program (MAP), directed by Mark Palmer of Brookhaven, was formally approved in 2011 in the US, that a systematic effort started to develop and demonstrate the concepts and critical technologies required to produce, capture, condition, accelerate and store intense beams of muons for a muon collider on the Fermilab site. Although MAP was wound down in 2014, it generated a reservoir of expertise and enthusiasm that the current international effort on physics, machine and detector studies can not do without.

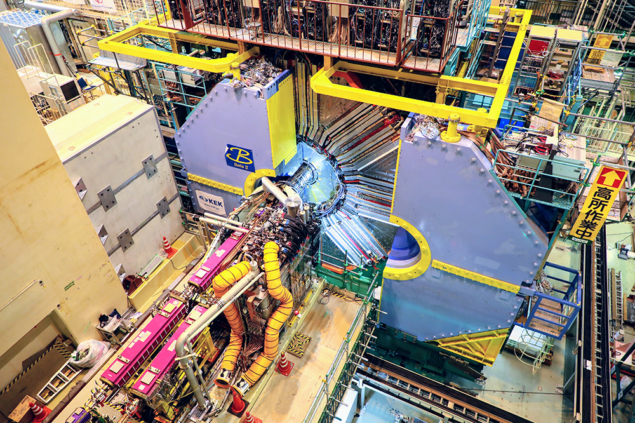

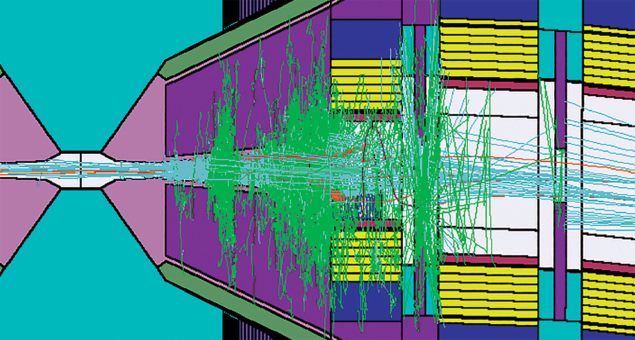

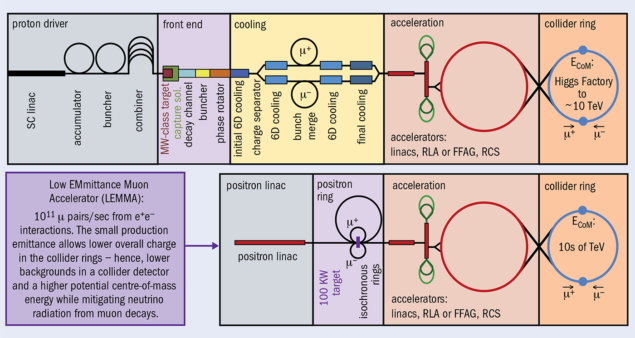

So far, two concepts have been proposed for a muon collider (figure 1). The first design, developed by MAP, is to shoot a proton beam into a target to produce pions, many of which decay into muons. This cloud of muons (with positive and negative charge) is captured and an ionisation cooling system of a type first imagined by Budker rapidly cools the muons from the showers to obtain a dense beam. The muons are cooled in a chain of low-Z absorbers in which they lose energy by ionising the matter, reducing their phase space volume; the lost energy would then be replaced by acceleration. This is so far the only concept that can achieve cooling within the timeframe of the muon lifetime. The beams would be accelerated in a sequence of linacs and rings, and injected at full energy into the collider ring. A fully integrated conceptual design for the MAP concept remains to be developed.

The unique potential of a multi-TeV muon collider deserves a strong commitment to fully demonstrate its feasibility

The alternative approach to a muon collider, proposed in 2013 by Mario Antonelli of INFN-LNF and Pantaleo Raimondi of the ESRF, avoids a specific cooling apparatus. Instead, the Low Emittance Muon Accelerator (LEMMA) scheme would send 45 GeV positrons into a target where they collide with electrons to produce muon pairs with a very small phase space (the energy of the electron and positron in the centre-of-mass frame are small, so little transverse momentum can be generated). The challenge with LEMMA is that the probability for a positron to produce a muon pair is exceedingly low, requiring an unprecedented positron-beam current and inducing a high stress in the target system. The muon beams produced would be circulated about 1000 times, limited by the muon lifetime, in a ring collecting muons produced from as many positron bunches as possible before they are accelerated and collided in a fashion similar to the proton-driven scheme of MAP. The low emittance of the LEMMA beams potentially allows the use of lower muon currents, easing the challenges of operating a muon collider due to the remnants of the decaying muons. The initial LEMMA scheme offered limited performance in terms of luminosity, and further studies are required to optimise all parameters of the source before capture and fast acceleration. With novel ideas and a dedicated expert team, LEMMA could potentially be shown to be competitive with the MAP scheme.

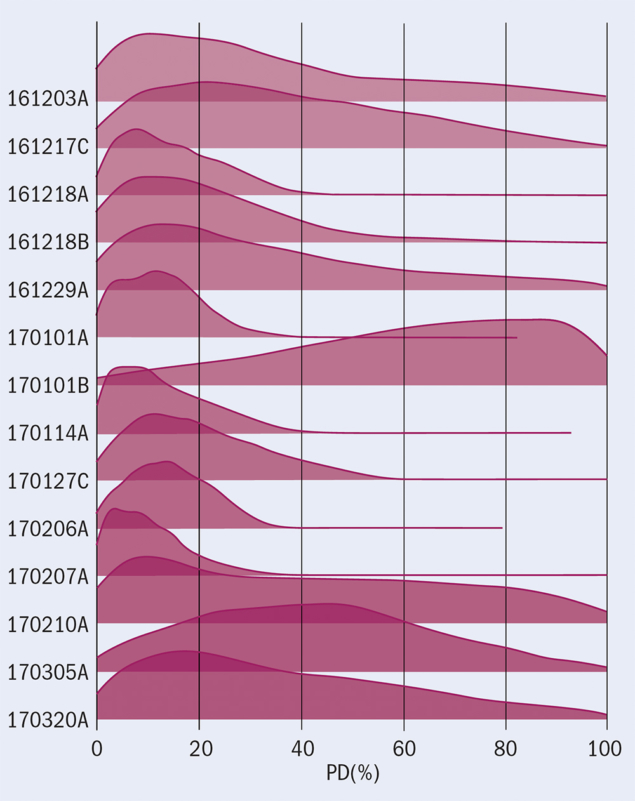

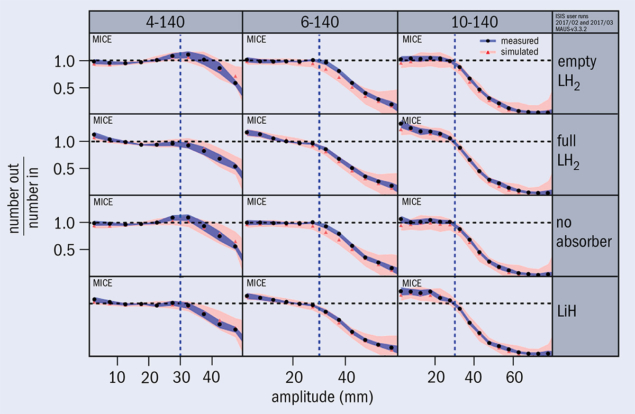

Concerning the ambitious muon ionisation-cooling complex (figure 2), which is the key challenge of MAP’s proton-driven muon-collider scheme, the Muon Ionization Cooling Experiment (MICE) collaboration recently published results demonstrating the feasibility of the technique (CERN Courier March/April 2020 p7). Since muons produced from proton interactions in a target emerge in a rather undisciplined state, MICE set out to show that their transverse phase-space could be cooled by passing the beam through an energy-absorbing material and accelerating structures embedded within a focusing magnetic lattice – all before the muons have time to decay. For the scheme to work, the cooling (squeezing the beam in transverse phase space) due to ionisation energy loss must exceed the heating due to multiple Coulomb scattering within the absorber. Materials with low multiple scattering and a long radiation length, such as liquid hydrogen and lithium hydride, are therefore ideal.

MICE, which was based at the ISIS neutron and muon source at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK, was approved in 2005. Using data collected in 2018, the MICE collaboration was able to determine the distance of a muon from the centre of the beam in 4D phase space (its so-called amplitude or “single-particle emittance”) both before and after it passed through the absorber, from which it was possible to estimate the degree of cooling that had occurred. The results (figure 3) demonstrated that ionisation cooling occurs with a liquid-hydrogen or lithium-hydride absorber in place. Data from the experiment were found to be well described by a Geant4-based simulation, validating the designs of ionisation cooling channels for an eventual muon collider. The next important step towards a muon collider would be to design and build a cooling module combining the cavities with the magnets and absorbers, and to achieve full “6D” cooling. This effort could profit from tests at Fermilab of accelerating cavities that can operate in a very high magnetic field, and also from the normal-conducting cavity R&D undertaken for the CLIC study, which pushed accelerating gradients to the limit.

Collider ring

The collider ring itself is another challenging aspect of a muon collider. Since the charge of the injected beams decreases over time due to the random decays of muons, superconducting magnets with the highest possible field are needed to minimise the ring circumference and thus maximise the average number of collisions. A larger muon energy makes it harder to bend the beam and thus requires a larger ring circumference. Fortunately, the lifetime of the muon also increases with its energy, which fully compensates for this effect. Dipole magnets with a field of 10.5 T would allow the muons to survive about 2000 turns. Such magnets, which are about 20% more powerful than those in the LHC, could be built from niobium-tin (Nb3Sn) as used in the new magnets for the HL-LHC (see Taming the superconductors of tomorrow).

The electrons and positrons produced when muons decay pose an additional challenge for the magnet design. The decay products will hit the magnets and can lead to a quench (whereby the magnet suddenly loses its superconductivity, rapidly releasing an immense amount of stored energy). It is therefore important to protect the magnets. The solutions considered include the use of large-aperture magnets in which shielding material can be placed, or designs where the magnets have no superconductor in the plane of the beam. Future magnets based on high-temperature superconductors could also help to improve the robustness of the bends against this problem since they can tolerate a higher heat load.

Other systems necessary for a muon collider are only seemingly more conventional. The ring that accelerates the beam to the collision energy is a prime example. It has to ramp the beam energy in a period of milliseconds or less, which means the beam has to circulate at very different energies through the same magnets. Several solutions are being explored. One, featuring a so-called fixed-field alternating-gradient ring, uses a complicated system of magnets that enables particles at a wider than normal range of energies to fly on different orbits that are close enough to fit into the same magnet apertures. Another possibility is to use a fast-ramping synchrotron: when the beam is injected at low energy it is kept on its orbit by operating the bending magnets at low field. The beam is then accelerated and the strength of the bends is increased accordingly until the beam can be extracted into the collider. It is very challenging to ramp superconducting magnets at the required speed, however. Normal-conducting magnets can do better, but their magnetic field is limited. As a consequence, the accelerator ring has to be larger than the collider ring, which can use superconducting magnets at full strength without the need to ramp them. Systems that combine static superconducting and fast-ramping normal-conducting bends have been explored by the MAP collaboration. In these designs, the energy in the fields of the fast-ramping bends will be very high, so it is important that the energy is recuperated for use in a subsequent accelerating cycle. This requires a very efficient energy-recovery system which extracts the energy after each cycle and reuses it for the next one. Such a system, called POPS (“power for PS”), is used to power the magnets of CERN’s Proton Synchrotron. The muon collider, however, requires more stored energy and much higher power flow, which calls for novel solutions.

High occupancy

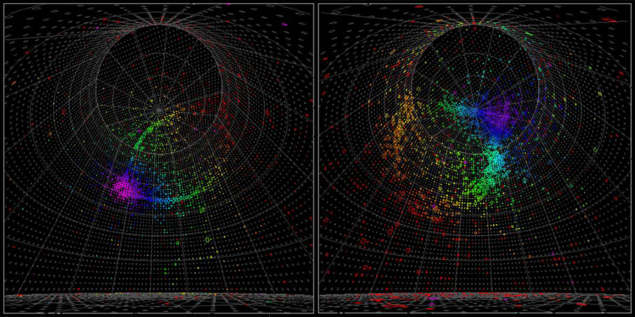

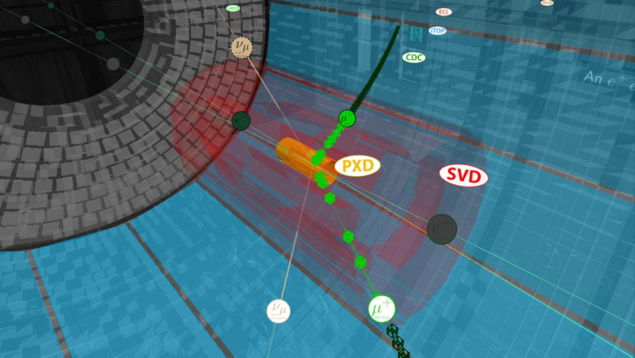

Muon decays also induce the presence of a large amount of background in the detectors at a muon collider – a factor that must be studied in detail since it strongly depends on the beam energy at the collision point and on the design of the interaction region. The background particles reaching the detector are mainly produced by the interactions between the decay products of the muon beams and the machine elements. Their type, flux and characteristics therefore strongly depend on the machine lattice and the configuration of the interaction point, which in turn depends on the collision energy. The background particles (mainly photons, electrons and neutrons) may be produced tens of metres upstream of the interaction point. To mitigate the effects of the beam-induced background inside the detector, tungsten shielding cones, called nozzles, are proposed in this configuration and their opening angle has to be optimised for a specific beam energy, which affects the detector acceptance (see figure 4). Despite these mitigations, a large particle flux reaches the detector, causing a very high occupancy in the first layers of the tracking system, which impacts the detector performance. Since the arrival time in each sub-detector is asynchronous with respect to the beam crossing, due to the different paths taken by the beam-induced background and the muons, new-generation 4D silicon sensors that allow exploitation of the time distribution will be needed to remove a significant fraction of the background hits.

Energy expansion

It was recently demonstrated, by a team supported by INFN and Padova University in collaboration with MAP researchers, that state-of-the-art detector technology for tracking and jet reconstruction would make one of the most critical measurements at a muon collider – the vector-boson fusion channel μ+μ– → (W*W*) ν ν → H ν ν, with H → b b – feasible in this harsh environment, with a high level of precision, competitive to other proposed machines (figure 5). A muon collider could in principle expand its energy reach to several TeV with good luminosity, allowing unprecedented exploration in direct searches and high-precision tests of Standard Model phenomena, in particular the Higgs self-couplings.

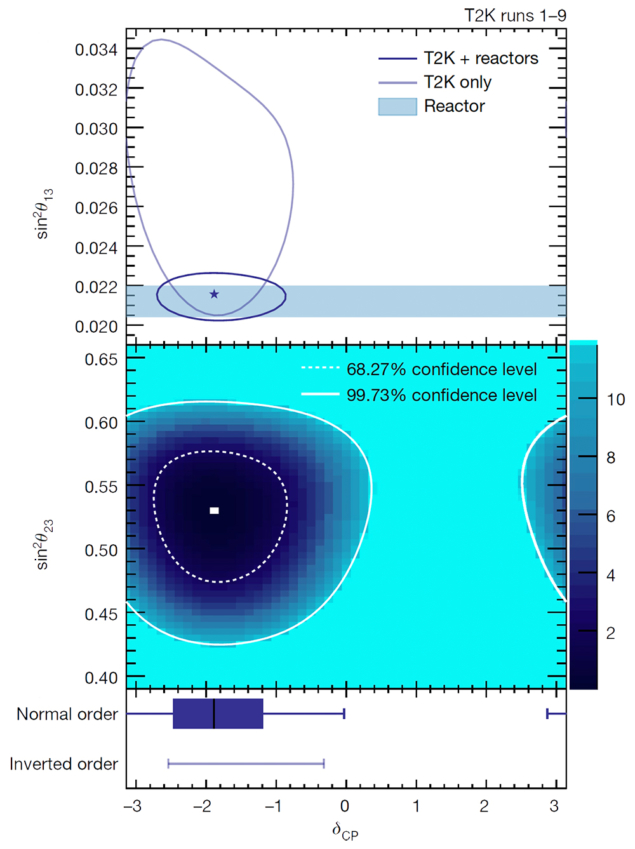

The technology for a muon collider also underpins a so-called neutrino factory, in which beams of equal numbers of electron and muon neutrinos are produced from the decay of muons circulating in a storage ring – in stark contrast to the neutrino beams used at T2K and NOvA, and envisaged for DUNE and Hyper-K, which use neutrinos from the decays of pions and kaons from proton collisions on a fixed target. In such a facility it is straightforward to tune the neutrino-beam energy because the neutrinos carry away a substantial fraction of the muon’s energy. This, combined with the excellent knowledge of the beam composition and energy spectrum that arises from the precise knowledge of muon-decay characteristics, makes a neutrino factory an attractive place to measure neutrino oscillations with great precision and to look for oscillation phenomena that are outside the standard, three-neutrino-mixing paradigm. One proposal – nuSTORM, an entry-level facility proposed for the precise measurement of neutrino-scattering and the search for sterile neutrinos – can provide the ideal test-bed for the technologies required to deliver a muon collider.

Muon-based facilities have the potential to provide lepton–antilepton collisions at centre-of-mass energies in excess of 3 TeV and to revolutionise the production of neutrino beams. Where could such a facility be built? A 14 TeV muon collider in the 27 km-circumference LHC tunnel has recently been discussed, while another option is to use the LHC tunnel to accelerate the muons and construct a new, smaller tunnel for the actual collider. Such a facility is estimated to provide a physics reach comparable to a 100 TeV circular hadron collider, such as the proposed Future Circular Collider, FCC-hh. A LEMMA-like positron driver scheme with a potentially lower neutrino radiation could possibly extend this energy range still further. Fermilab, too, has long been considered a potential site for a muon collider, and it has been demonstrated that the footprint of a muon facility is small enough to fit in the existing Fermilab or CERN sites. However, the realistic performance and feasibility of such a machine would have to be confirmed by a detailed feasibility study identifying the required R&D to address its specific issues, especially the compatibility of existing facilities with muon decays. Minimising off-site neutrino radiation is one of the main challenges to the design and civil-engineering aspects of a high-energy muon collider because, while the interaction probability is tiny, the total flux of neutrinos is sufficiently high in a very small area in the collider plane to produce localised radiation that can reach a fraction of natural-radiation levels. Beam wobbling, whereby the lattice is modified periodically so that the neutrino flux pointing to Earth’s surface is spread out, is one of the promising solutions to alleviate the problem, although it requires further studies.

It was only when the Muon Accelerator Program was formally approved in 2011 in the US that a systematic effort started

A muon collider would be a unique lepton-collider facility at the high-energy frontier. Today, muon-collider concepts are not as mature as those for FCC-ee, CLIC, ILC or CEPC. It is now important that a programme is established to prove the feasibility of the muon collider, address the key remaining technical challenges, and provide a conceptual design that is affordable and has an acceptable power consumption. The promises for the very high-energy lepton frontier suggests that this opportunity should not be missed.