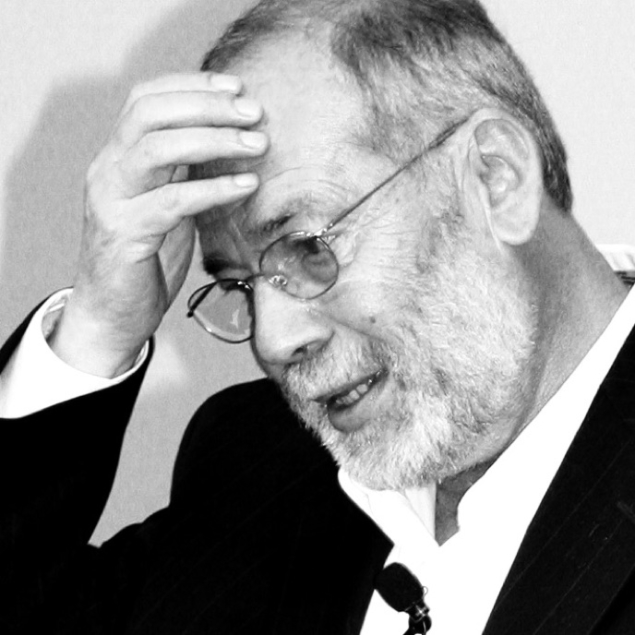

John Thompson, a senior physicist at the UK’s Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL), passed away on 20 August.

John obtained his PhD in nuclear physics for work on the Van de Graaff accelerator at the University of Liverpool in the early 1960s before moving to the University of Manitoba, Canada to work on particle physics. He then took a post at Daresbury Laboratory in the UK to work on experiments using the 5 GeV electron synchrotron, NINA. His first experiment involved a measurement of the total hadron photoproduction cross sections for energies from 1 to 4 GeV. These precise measurements have never been superseded and remain the definitive values documented by the Particle Data Group.

John was central to the formation of Daresbury’s LAMP group, which focused on a series of hadronic photoproduction experiments. He played a leading role in the development of the 480-element lead–glass array for studies of neutral particle production in the final phase of the LAMP experiment.

During this period, following the discovery of deep inelastic scattering at SLAC and DESY, John together with his colleagues became involved in the plans to study deep inelastic scattering at the higher energies afforded by the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) at CERN. He became a founding member of the European Muon Collaboration (EMC), which would go on to do experiments in the high-intensity muon beam at CERN.

John was a first rate, hands-on experimental physicist

As NINA came to the end of its life and Daresbury moved to host one of the first dedicated “light sources”, John moved with other colleagues in particle physics to RAL. Interested in the production of high-energy photons at the EMC, he organised the transfer of the LAMP lead–glass array from the UK to CERN to study the production of photons in the forward direction. In the final phase of the EMC activities he successfully led a team from RAL that implemented the change to a polarised target – a very difficult procedure that had to be done in just a few months.

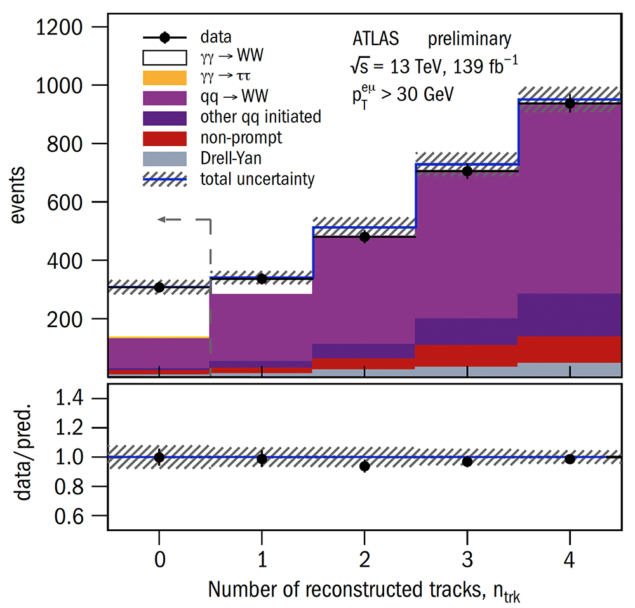

In the 1980s John led the RAL group into the ALEPH experiment at CERN’s Large Electron Positron collider, LEP. The group undertook the task of building the end cap electromagnetic calorimeters, which operated successfully during the 11 years of ALEPH operations. John became heavily involved with early results for which the calorimeter performance was crucial, such as its use in counting the number of neutrino species from the radiative return reaction e+e– → µµγ. During the LEP2 period in the late 1990s, John’s major contribution concerned the measurement of the W mass and width. This led to a highly productive collaboration between the Imperial College and RAL ALEPH teams, and saw John become instrumental in guiding the students. Following his retirement from RAL, he was appointed visiting professor at Imperial where he was lead author on the publication of the final ALEPH W mass measurements. He continued to advise and guide students, and took charge of graduate lectures until recently, when failing health made it difficult for him to do so.

John was a first rate, hands-on experimental physicist. He had a talent for understanding the difficulties of others and involving himself selflessly to help them progress. He always had a patient, calm, happy and relaxed manner, and will be sadly missed.