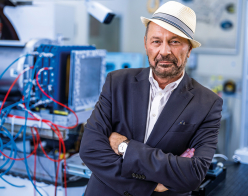

Bart Van de Vyver relates his experience of technology transfer when he left CERN to create a start-up company exploiting biotechnology research.

A dynamic technology-transfer department is only one of many factors determining how often and how successfully start-up companies will be created. This belief is not based on any solid evidence, but on a single example with, at best, anecdotal value. The example is from my own experience over the past three years in helping to create SpinX Technologies, a start-up company developing instruments for pharmaceutical research and clinical diagnostics.

The SpinX story started around Christmas 2001 in a branch of IKEA. Following a casual conversation with a stranger sharing his table at the cafeteria, Piero Zucchelli from CERN could not let go of one thought. Of the myriad technologies used or developed at CERN, there had to be some just waiting to be exploited outside of particle physics. Since my summer-student days when Piero had been my supervisor, we frequently worked together and I had become interested in business as well as in molecular biology. Over the next few weeks, we spent countless hours brainstorming how technology at CERN could be applied to biotechnology.

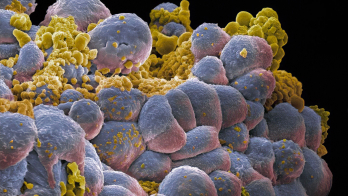

Gradually, we zoomed in on a field where many advances had been the work of physicists: microfluidics. The idea behind microfluidic devices, often called lab-on-a-chip systems, is to perform biochemical experiments using sub-microlitre volumes rather than millilitre volumes. Liquids are manipulated by running them through channels no wider than a human hair laid out on a silicon or plastic substrate. The applications are mostly biochemical and range from food testing to drug discovery.

What struck us most is that all microfluidic devices were specialized for a specific type of biochemical experiment characterized by a well defined but fixed sequence of operations. There were none where different protocols could be “programmed” on the same chip by setting a series of valves. Before long, Piero had come up with a valve implementation using an infrared laser. With this Virtual Laser Valve, everything started to fall into place and we soon had all the elements for a programmable microfluidics platform.

At some point a friend at CERN suggested that, if we were serious about this idea and believed it had commercial value, we should take it to serious investors. He would make the introductions. With nothing but an idea, we crossed the doorstep at Index Ventures, a venture-capital fund managing €750 million. It took us half a year to build their interest. For us, this was a turning point. Leaving the comfort of stable, well paid positions in research, we had to devote all our time and energy to SpinX with no guarantee of success.

Our case illustrates where a technology-transfer department can make a very real contribution, but also where it is essentially powerless. Contacts with venture-capital funds, law firms, business consultants and so on are obviously helpful to any aspiring entrepreneur, and a technology-transfer department is ideally placed to build this kind of network. But the key factor in attracting high-quality capital is commitment. Francesco de Rubertis, a partner at Index Ventures, says, “We do not invest in technologies, but in the teams that can make them happen.” Venture capitalists expect the people behind an idea to be entirely devoted to their start-up. Anything less is a sure deal-breaker.

Throughout the process, the interaction with CERN in general and technology transfer at CERN in particular could not have been more productive. Both of us were offered leave from the moment we started to work full time until the moment the investors committed. During the due-diligence process, the technology-transfer department provided us in record time with a legal statement clarifying the ownership of the intellectual property.

We did convince Index Ventures of our business concept, SpinX was created and the experience has been extremely rewarding. Today we are a company of 10 people, we have identified the first application of our technology, we have built a working system for that application and we are talking with several pharmaceutical companies interested in evaluating the system.

Would SpinX exist if it hadn’t been for CERN? I doubt it. We may not have started from any specific technology at CERN, but we could not have done it without the experience built there. It was at CERN that we learned the importance and benefits for international, multi-disciplinary teams to “try the impossible”. With 10 people, SpinX has seven nationalities and six doctorates, with backgrounds ranging from physics and engineering to biochemistry and enzymology. Like particle detectors at CERN, the instrument we developed uses a host of off-the-shelf components from widely varying industries. Finally, there is the undeniable value of the CERN brand. Recently, following a conference presentation of the technology to a senior executive at Eli Lilly, he commented that if former CERN physicists could not get it to work, then nobody could!