Thirty years ago, physicists from Harvard University set out to build a portable antiproton trap. They tested it on electrons, transporting them 5000 km from Nebraska to Massachusetts, but it was never used to transport antimatter. Now, a spin-off project of the Baryon Antibaryon Symmetry Experiment (BASE) at CERN has tested their own antiproton trap, this time using protons. The ultimate goal is to deliver antiprotons to labs beyond CERN’s reach.

“For studying the fundamental properties of protons and antiprotons, you need to take extremely precise measurements – as precise as you can possibly make it,” explains principal investigator Christian Smorra. “This level of precision is extremely difficult to achieve in the antimatter factory, and can only be reached when the accelerator is shut down. This is why we need to relocate the measurements – so we can get rid of these problems and measure anytime.”

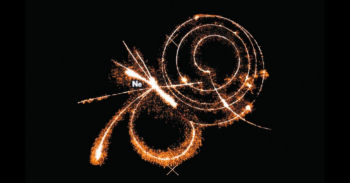

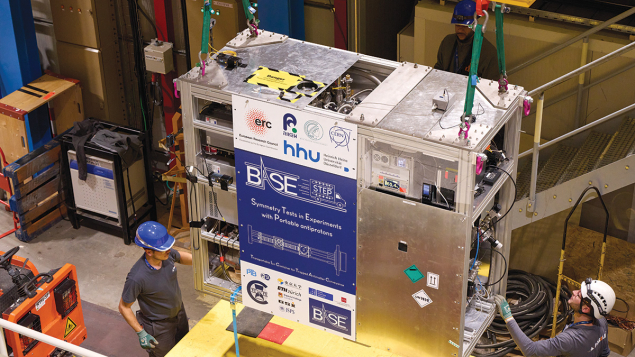

The team has made considerable strides to miniaturise their apparatus. BASE-STEP is far and away the most compact design for an antiproton trap yet built, measuring just 2 metres in length, 1.58 metres in height and 0.87 metres across. Weighing in at 1 tonne, transportation is nevertheless a complex operation. On 24 October, 70 protons were introduced into the trap and lifted onto a truck using two overhead cranes. The protons made a round trip through CERN’s main site before returning home to the antimatter factory. All 70 protons were safely transported and the experiment with these particles continued seemlessly, successfully demonstrating the trap’s performance.

Antimatter needs to be handled carefully, to avoid it annihilating with the walls of the trap. This is hard to achieve in the controlled environment of a laboratory, let alone on a moving truck. Just like in the BASE laboratory, BASE–STEP uses a Penning trap with two electrode stacks inside a single solenoid. The magnetic field confines charged particles radially, and the electric fields trap them axially. The first electrode stack collects antiprotons from CERN’s antimatter factory and serves as an “airlock” by protecting antiprotons from annihilation with the molecules of external gases. The second is used for long-term storage. While in transit, non-destructive image-current detection monitors the particles and makes sure they have not hit the walls of the trap.

“We originally wanted a system that you can put in the back of your car,” says Smorra. “Next, we want to try using permanent magnets instead of a superconducting solenoid. This would make the trap even smaller and save CHF 300,000. With this technology, there will be so much more potential for future experiments at CERN and beyond.”

With or without a superconducting magnet, continuous cooling is essential to prevent heat from degrading the trap’s ultra-high vacuum. Penning traps conventionally require two separate cooling systems – one for the trap and one for the superconducting magnet. BASE-STEP combines the cooling systems into one, as the Harvard team proposed in 1993. Ultimately, the transport system will have a cryocooler that is attached to a mobile power generator with a liquid-helium buffer tank present as a backup. Should the power generator be interrupted, the back-up cooling system provides a grace period of four hours to fix it and save the precious cargo of antiprotons. But such a scenario carries no safety risk given the miniscule amount of antimatter being transported. “The worst that can happen is the antiprotons annihilate, and you have to go back to the antimatter factory to refill the trap,” explains Smorra.

With the proton trial-run a success, the team are confident they will be able to use this apparatus to successfully deliver antiprotons to precision laboratories in Europe. Next summer, BASE-STEP will load up the trap with 1000 antiprotons and hit the road. Their first stop is scheduled to be Heinrich Heine University in Germany.

“We can use the same apparatus for the antiproton transport,” says Smorra. “All we need to do is switch the polarity of the electrodes.”