All galaxies are thought to contain a super-massive black hole (SMBH) at their centres, one of which was famously pictured for the first time by the Event Horizon Telescope only a few months ago (CERN Courier May/June 2019 p10). Both the size and activity of such SMBHs differ significantly from galaxy to galaxy: some galaxies contain an almost dormant black hole at their centre, while in others the SMBH is accumulating surrounding matter at a vast rate resulting in bright emission with energies ranging from the radio to the X-ray regime.

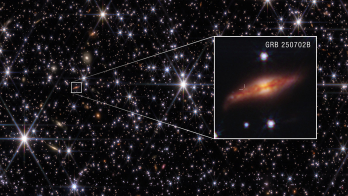

While solar-mass black holes can show dramatic variations in their emission on the time scale of days or even hours, such time scales increase with size, meaning that for an SMBH one would not expect much change during years or even centuries. However, observations during the past decade have revealed sudden increases. In 2010 the X-ray emission from a galaxy called GSN 069, which has a relatively small SMBH (400,000 solar masses), became 240 times brighter compared to observations in 1989 – turning it into an active galaxy. In such objects the matter falling into the central SMBH releases radiation when it approaches the event horizon (the boundary beyond which nothing can escape the black hole’s gravitational field).

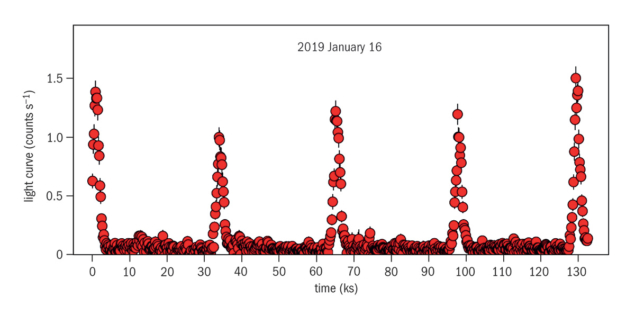

The brightness of the emission produced as the SMBH feeds on the surrounding disk of matter typically varies randomly on short time scales, a result of a change in accretion rate and turbulence in the disk. But subsequent observations with the European Space Agency’s X-ray satellite XMM-Newton in 2018 revealed never-before-seen behavior. The object emitted strong bursts of X-rays lasting about one hour. Even more surprising was that the bursts appeared to occur at very consistent intervals of nine hours. Follow-up observations in 2019 with both XMM-Newton and NASA’s Chandra X-ray telescope have now confirmed this picture. While simultaneous observations at radio wavelengths showed no variability, the intensity of the bursts at X-ray wavelengths decreased. An extrapolation of this decrease indicates that, by now, the bursts should have fully disappeared, although further observations are needed to confirm this.

The team behind the latest observations, published in Nature, has no clear explanation of what causes such extreme periodic behaviour from such a massive object. One possibility, claims the paper, is that it is the result of a second SMBH orbiting the main one: each time it crosses the disk of matter a burst would be expected. However, the associated variation would be expected to be more smooth than is observed. Furthermore, no such bursts were seen in the 2010 observations, making this theory implausible. Another explanation is that a semi-destroyed star is currently orbiting the SMBH, disturbing the accretion rate. The last and most probable hypothesis is that the quasi-periodic explosions are a result of complex oscillations in the disk of hot matter surrounding the SMBH induced by instabilities. The authors make it clear, however, that deeper studies are required to fully explain this new phenomenon.

Although only observed for the first time in GSN 069, it could very well be that other galaxies exhibit a similar behaviour. Other SMBHs with masses many orders of magnitude larger could exhibit the same periodic burst but on time scales of months or years, explaining why no one has ever noticed them. So while it could be that GSN 069 is simply a strange galaxy, the finding could have large implications for galaxies in general.

Further reading:

G Miniutti et al. 2019 Nature 573 381.