It has long been predicted that the very strong tidal forces of supermassive black holes at the centre of galaxies are able to disrupt stars venturing too close. Observational evidence for this phenomenon has now been obtained by two X-ray observatories – ESA’s XMM-Newton and NASA’s Chandra.

The story of this discovery goes back to July 1992, when the German Roentgen satellite (ROSAT) observed strong X-ray emission from an unknown source that happened to be in its field of view. This source, called RX J1242.6-1119, must have brightened by at least a factor of 20 during the previous one-and-a-half years, as it had not been detected between December 1990 and January 1991 during the ROSAT All-Sky Survey. Then in January 1999 the 1.5 m Danish telescope at La Silla, Chile, found two distant galaxies (redshift z = 0.05) within the X-ray position error circle, but surprisingly neither of them showed evidence for hosting an active galactic nucleus.

If the X-ray outburst was indeed associated with one of these non-active galaxies, the most likely interpretation of its origin was the tidal disruption of a star by a supermassive black hole. To test this hypothesis, the two galaxies were observed by the Chandra X-ray Observatory during March 2001, and a faint X-ray emission was detected at the centre of one of the two galaxies. Finally, in June 2001, a follow-up observation with XMM-Newton allowed the X-ray spectrum of this source to be obtained, although it was about 200 times dimmer than the outburst detected in July 1992 by ROSAT. The radiation was found to be widespread in energy – the characteristic emission of matter close to a black hole.

Like putting together the pieces of a puzzle in a detective story, these new observations now tell us what happened at the centre of this galaxy. A doomed star ventured too close to a massive black hole, and once close enough began to feel the extreme tidal forces exerted by the black hole. The difference in gravity acting on the front and back of the star first stretched it and then completely ripped it apart. Part of the stellar debris was pulled toward the black hole. In the extreme conditions close to the black hole’s event horizon the gas heated itself up enormously, to millions of degrees, and before disappearing into the black hole forever, the gas emitted a brilliant flare of X-ray radiation – a “last cry for help” from the dying star. When re-observed with Chandra and XMM-Newton nine years later, the X-ray emission had dropped dramatically but not yet faded away completely. We can still see some of the afterglow emitted by the remaining gas that has not yet been swallowed by the black hole.

The data collected for RX J1242.6-1119 are the best evidence yet for such a tidal disruption event. Only two other suspicious flares that could be similar events have been found in other galaxies. Astronomers estimate that these events happen about once every 10,000 years in a galaxy. If this was going to happen around the black hole at the centre of our own Milky Way galaxy, it would become a hundred billion times brighter in X-rays than it is now, outshining every X-ray source in the sky, other than the Sun.

Further reading

S Komossa et al. 2004 ApJ 603 L17.

Picture of the month

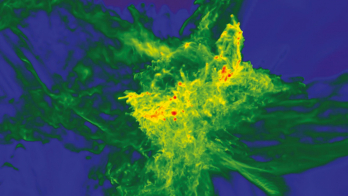

This X-ray map of the entire sky is a beautiful example of recycling “trash” data from a satellite. It was constructed using 20 million seconds of data from the Proportional Counter Array of NASA’s Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer (RXTE) when the satellite was moving between pointed observations. Because RXTE has been in operation for about eight years, it has now covered almost the entire sky with these “slew” observations, enabling the construction of the most precise map at X-ray energies between 3 and 20 keV. The plane of our galaxy is clearly seen, running horizontally along the middle of the image, and the map contains hundreds of clearly detected X-ray sources, including objects inside the Milky Way and beyond. (Credit: M Revnivtsev, S Sazonov, K Jahoda, M Gilfanov; NASA.)