A look at the work of a prize-winning artist who finds inspiration in CERN.

Observer and observed

Image credit: Haunch of Venison, copyright Keith Tyson 2009.

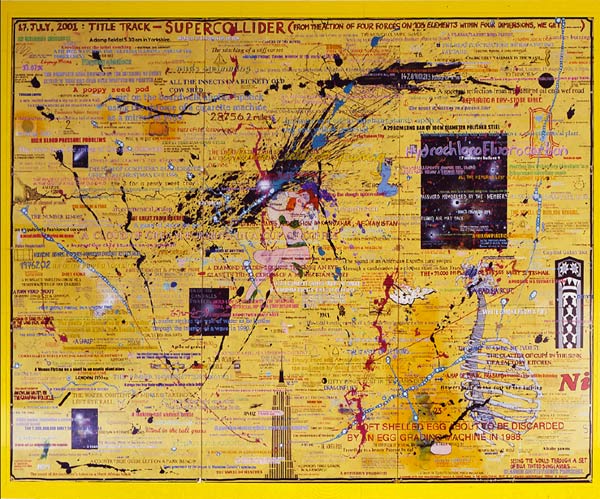

It should come as no surprise then, that the work at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN has been the jumping-off point for some of Keith’s most critically acclaimed work. His 2002 exhibition “Supercollider”, shown at the South London Gallery in the UK, took its title from the goings on at CERN. The title piece of the exhibition (right) was a giant studio drawing with the subtitle “From the Action of Four Forces on 103 elements within four dimensions, we get…” and needs no explanation to any scientist. Random quotes drawn from everything from planetary charts to entries in anonymous diaries, combined with splashes of colour and pictures of a red-haired model wearing an itsy-bitsy, green bikini, are some of the myriad miscellaneous items that collide on this giant painting and which reflect the wonderful diversity of the world created “from the action of four forces…”. Another mixed-media piece, Bubble Chambers: 2 Discrete Molecules of Simultaneity, bursts with random quotes with random dates from 1325 to 2002 dotted across a surface that is crammed with molecules represented as bubbles in reds, blacks, blues, pinks and whites.

Both of these pieces are like a mirror held up to the viewer. Look at them both and, inevitably, the temptation kicks in to start drawing conclusions or to make narratives out of the random juxtapositions: the mind’s processes writ large. Like much of Keith’s work, he is interested in the way that we make sense of the world: as the observer and the observed; the viewer and the artist; and the ways in which we use logic, counter-intuition and intuition to make these discoveries. In essence, we are all in this artistic experiment together, discovering who and what we are in the act of looking – the artist included.

But if looking is important to Keith, it wasn’t until 2009 that he finally came to take his own look at CERN. Talk to him about his visit and he says that what impressed him above everything was “not so much the LHC or the machines themselves, as the way in which the scientists at CERN meet ideas head on and change the way we think about ourselves”.

He came as part of a private party of artists, including fellow British artist Cerith Wynn-Jones and the German experimentalist Ali Janka, who were shown round the CERN complex by the communication team in September 2009. In many ways, visting CERN was a homecoming for Keith and one that he found profoundly moving. He encountered an international community dedicated to breaking the boundaries of knowledge and challenging the world of appearances – ideals that are so close to his heart and mind too.

Image credit: Haunch of Venison, copyright Keith Tyson 2009.

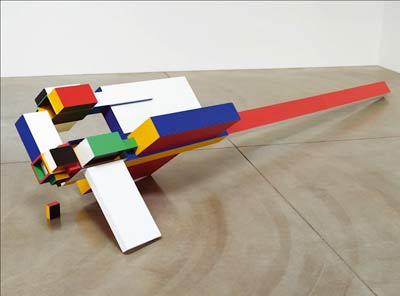

For someone who is so omnivorous in his wish to gain knowledge, physics isn’t the only science that fascinates him. Chemistry and mathematics engage him too. Some of his most famous pieces include the fractal dice, part of the Geno Pheno series (2005), which explores the worlds of cause and effect and takes its title from genetics. The work explores the idea of what is a starting point – an artwork’s DNA, so to speak; its physical manifestation or where it leads. The fractal dice pieces are three-dimensional aluminium and plastic sculptures, in vibrant primary colours – reds, blacks, greens and yellows. They are assembled in galleries around the world where they are shown according to a mathematical system, known as random iterative-functions systems, which is supplied to the curators by the artist. The form of each piece – sometimes as many as 14 are shown at any one time, sometimes fewer – is determined by the rolls of a dice and by the rules set out by the artist. For example, rule number one determines which colour a particular side of the sculpture should be. Complexity and unpredictability are both shown to be crucial components of the creative process, which involves both decisions and chance.

Image credit: Haunch of Venison, copyright Keith Tyson 2009.

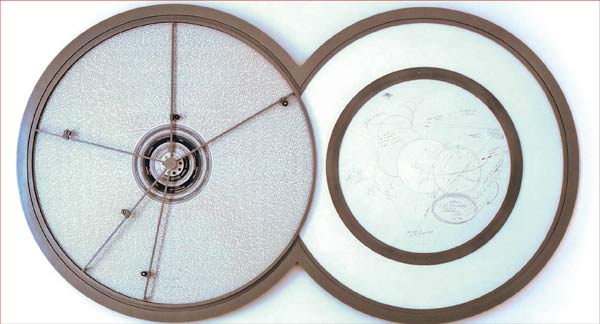

This love of engaging with different sciences and their processes shows how critical Keith is of being enslaved by any one knowledge system. His sculptural piece, Teleological Accelerator (2003), clearly shows this (top right). It is a massive wall installation measuring 5 m across, with two interlocking metal discs made of aluminium and steel that comprise a diagram of words and concepts written in pencil, ranging over all kinds of human achievements as well as an accumulation of scientific definitions. The flexible indicators can be twisted by the viewer so that the artist playfully conveys his idea that teleology is whatever you can make of it. Meaning is not a fixed point: it is always changing.

Pushing boundaries

Image credit: Haunch of Venison, copyright Keith Tyson 2009.

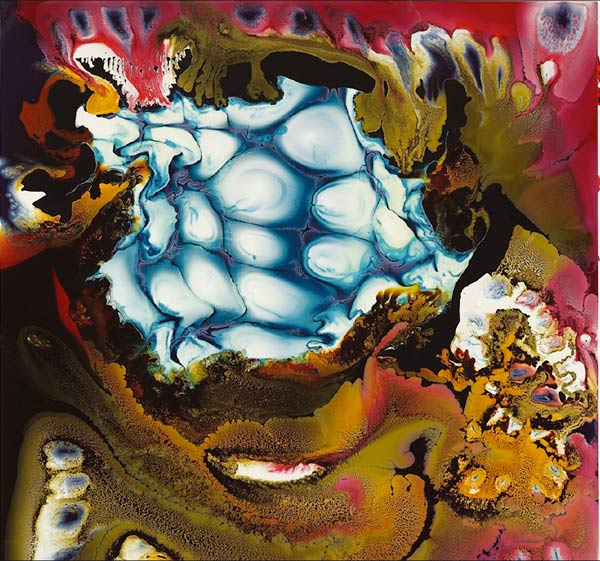

If much of Keith’s work shows a great indebtedness to science and a love of it as a knowledge system, and form of enquiry about the world, some of his latest work also shows an awe-inspiring sense of nature. After all, as Keith so eloquently says, “Science and art are the ways in which we describe the world. Nature is the world.” The 2009 work Mathematical Nature Painting Nested (bottom right), currently being shown at the Royal Academy of Art, London, is a portrait of original transformations. Paints and chemicals have been poured onto a primed aluminium sheet and a painting takes shape thanks to the hydrophic reaction that forms the basis of the painting. This is the first phase. In the second phase, Keith determines the appearance of the painting, as far as he can, to make it resemble cells structures or geographical strata, according to the way that he dries the paint over the following month.

Like particle physics itself, Keith is pushing boundaries, working within limits and constraints and outside them too: “I am not interested in the role of the artist as creator. Art is a vehicle of enquiry and the role of the artist is much more like that of Christopher Columbus – we are navigators and discoverers of what is already out there in the world but has yet to be discovered.”

He could just as easily be talking about the role of the scientist, but he is clear about how different artists and scientists are, as well as the ways in which the arts and science could and should interact: “Artists, unlike scientists, are not attempting to model the world. They are trying to engage the viewer with the wonder of it. If you attempt to marry and equate art with science, then you fail. If you allow what is not similar about art and science, and their different methods and processes to co-exist and thrive, then a real art/science collaboration and aesthetic will emerge. But at the end of the day, both art and science are united by one logic and one impulse – both are attempts to understand what it is to be human and the world around us.”

• For more information about Keith Tyson’s latest creations, see his official website at www.keithtyson.com.