A look back at a physicist whose bequest benefits women today.

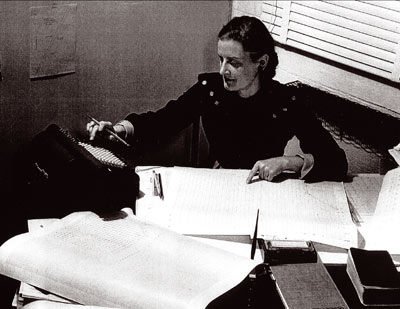

Image credit: Blewett family.

One of the most generous schemes to support women returning to physics – and possibly the most valuable to result from a personal bequest – is the M Hildred Blewett Fellowship of the American Physical Society (APS). When Hildred died in 2004, she left nearly all that she had to the APS to set up the scholarship, which funds a couple of women a year in the US or Canada to the tune of up to $45,000. So far, nine recipients have benefited from the bequest, including two in nuclear and particle physics – not far removed from Hildred’s own field of work in accelerator physics. Indeed, she played an important role in the design of accelerators on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as in the organization of their exploitation.

Hildred Hunt was born in Ontario on 28 May 1911. Her father, an engineer who became a minister, supported her interests in mathematics and physics, although the family did not have much money and Hildred had to take a time out from college – a factor that appears to have influenced the future bequest. Nevertheless, by 1935 she had graduated from the University of Toronto with a BA in physics and maths. Stints of research followed, first at the University of Rochester, New York, and then at Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory – which was still under Ernest Rutherford – together with her husband John Blewett, who had also studied in Toronto. After returning to the US, in 1938 Hildred joined Cornell University as a graduate student, with Hans Bethe as her thesis supervisor. Writing in APS News more than 60 years later, physicist Rosalind Mendell recalled Hildred saying that as John was working on magnetrons at General Electric (GE) “she had gone back for her doctorate because she loved physics and could no longer endure life as a ‘useless’ company wife” (Mendell 2005). Rosalind had arrived at Cornell in 1940, when she was just short of 20 years old, joining 50 men plus Hildred – “the cheerful, confident and breezy Canadian blonde”. Hildred took the younger woman under her wing, a characteristic that was seen later with other junior colleagues and was also reflected in her final bequest.

The entry of the US into the Second World War changed everything and by the summer of 1942, Bethe was working with Robert Oppenheimer in California on some of the first designs for an atomic bomb. In November Hildred joined GE’s engineering department; her thesis work was left behind, never to be fulfilled. While at GE she developed a method of controlling smoke pollution from factory chimneys. However after the war, a bright future opened up for scientific research in the US and in 1947 both Blewetts were hired by the newly established Brookhaven National Laboratory to work on particle accelerators. Hildred’s forte was in theoretical aspects, while John had already worked with betatrons at GE.

The Blewetts were part of the team that worked on the design and construction of a new accelerator that would reach an energy of 3 GeV, an order of magnitude higher than in any previous machine and in the range of cosmic-ray energies, hence the name of “Cosmotron”. The machine came into operation in 1952 and Hildred edited a special issue of Review of Scientific Instruments, which contained articles on many key aspects, some of which she also co-authored (Blewett 1953a).

Birth of the PS

That same year saw the emergence of the alternating gradient or “strong-focusing” technique, which offered the possibility for an accelerator to go up to much higher energies and gave birth to the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron (AGS) at Brookhaven. The idea was also conveyed to a group of physicists from several European countries who visited Brookhaven in the summer of 1952 to learn about the Cosmotron and how they might build a similar but somewhat larger machine for the nascent organization that would become CERN. Following the visit, and a busy period of study, the decision was indeed taken to build a strong-focusing machine of 25–30 GeV, the future Proton Synchrotron (PS). The group invited the two Blewetts and Ernest Courant – one of the inventors of the principle of strong focusing – to Europe to help plan the new laboratory.

By the end of March 1953, the provisional Council had agreed to build the strong-focusing machine, but as CERN did not yet officially exist, the work was split among groups in several European institutions. On six months’ leave from Brookhaven, the Blewetts went to Odd Dahl’s institute in Bergen, where they contributed to the initial design of the PS. The arrangement turned out to be more complex than initially thought, and they pushed to have everything moved to Geneva, once the site had been selected and ratified by the cantonal referendum in June 1953. The advance guard of the PS group, including the Blewetts, arrived there at the beginning of October. At the end of the month Geneva hosted a conference on the theory and design of an alternating-gradient proton synchrotron; Hildred edited the proceedings (Blewett 1953b).

Both Blewetts were full members of the PS group, engaged in all aspects, from theoretical research to cost estimates, and their collaboration continued, even after they returned to the US. By January 1954, the decision had been taken to build the 33 GeV AGS at Brookhaven, so the collaboration between the US and Europe was important to both. Hildred commented later that there were even times when “in many ways Brookhaven got more from the co-operation than CERN did” (Krige 1987). She returned to Geneva to attend accelerator conferences in 1956 and 1958, and visited CERN for three months in 1959, when the PS was near completion. Well known photos record her presence in the PS control room on the magical evening of 24 November when the “transition” took place; her written recollections still bring the day vividly to life (CERN Courier November 2009 p19).

Back in Brookhaven Hildred made major contributions to the design of the AGS, in particular she “presided over the design of the magnets” (Blewett 1980). Courant also recalls that she devised an elaborate programme to make detailed field measurements of each of the 240 magnets, which enabled the team to assign the positions of the magnets in the ring so as to minimize the effects of deviations from the design fields.

The AGS began operation in 1960, a few months after the PS at CERN. Alan Krisch, then a graduate student at Cornell, worked on a large-angle proton–proton scattering experiment, which was one of the first to be approved. Hildred “sort of adopted” him and he remembers her as a “formidable woman from whom he learnt much”. She was the one, for example, who suggested that the Cornell group acquire a trailer to provide a cleaner environment where they could collect their data near their AGS experiment. “It was a great idea,” he says, “and soon everyone had trailers.”

The Blewetts split up around that time, as professional divergences increased. These included, Krisch recalls, a disagreement about whether the AGS should add a high-intensity linac or colliding beams. After the divorce, Lee Teng, a colleague and friend, invited Hildred to the Argonne National Laboratory, where he had become director of the Particle Accelerator Division. “I remembered that at Brookhaven she got along very well with and was respected by all of the AGS users,” he says, so he suggested that Hildred become the liaison with the users of Argonne’s Zero Gradient Synchrotron (ZGS). She took on the work with characteristic dedication, bringing all of her experience from Brookhaven, taking care of the needs of the users. One of these was Krisch, who at 25 was a newly appointed assistant professor at the University of Michigan and spokesperson for one of the first experiments on the ZGS. Under Hildred, the experimental areas worked well, “probably the best of any place I’ve worked at”, he says. During this time at Argonne, papers by Hildred show that she continued to work on magnet design, as well as on costings for experimental facilities.

By 1967, on leave from Argonne, she was already involved with the 300 GeV project at CERN, for example as co-ordinator of utilization studies across the member states to look into the exploitation of the machine that would become the Super Proton Synchrotron (ECFA 1967). She joined the CERN staff in 1969 and collaborated in the Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR), which started up in 1971. That same year she was heavily involved in the organization of the 8th International Conference on High-energy Accelerators in Geneva, nearly a quarter of a century after the conference (also in Geneva) that had foreshadowed the PS. She ran the finances of the ISR Division, keeping a careful eye on how resources were spent, as well as being secretary of the ISR Committee (ISRC), serving the new community of users at CERN. Again, the users included Krisch, this time as the first US spokesperson on a CERN experiment, together with a trailer flown over from Argonne; and again Hildred’s expertise proved invaluable, advising on how to run the cabling etc. By the time she retired she had been secretary for 60 meetings of the ISRC and left behind her a perfect organization, in the words of her successor.

She retired in August 1976, but remained at CERN until July 1977 as a scientific associate. During this final year, reports were published on the concept for a 100 GeV electron–positron machine and on studies of 400 GeV superconducting proton storage rings – the future Large Electron–Positron collider and Large Hadron Collider, respectively – both of which involved Hildred (Bennet et al. 1977 and Blechschmidt et al. 1977). She also organized the 1st International School of Particle Accelerators “Ettore Majorana” in Erice, which laid the foundations for the CERN Accelerator School.

The recollections of some of the people who knew Hildred not only paint a picture of a strong woman who cared a great deal for others, but also give some insight into her interests beyond physics. Mendell remembers that they walked together on the Physics Department hikes at Cornell and Courant recalls that she was “an avid folk dancer”, organizing weekly classes in which he and his wife participated enthusiastically. Krisch recalls that during his third encounter with Hildred at CERN, she invited him to Geneva’s English Theatre Club to see her star as the Bulgarian heroine in George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man.

After a few years in Oxford, which suited her interests in music, amateur dramatics and fine arts, Hildred returned to Canada to be closer to her brother and his family. She died in Vancouver in June 2004, at the age of 93. Her career was characterized by her concern that others too should be able to make the most of their time in the field she clearly enjoyed – from the young people she mentored to the user communities she served in several major laboratories and to the beneficiaries of her generous bequest.