Something happened at CERN in 1989 that changed the world forever.

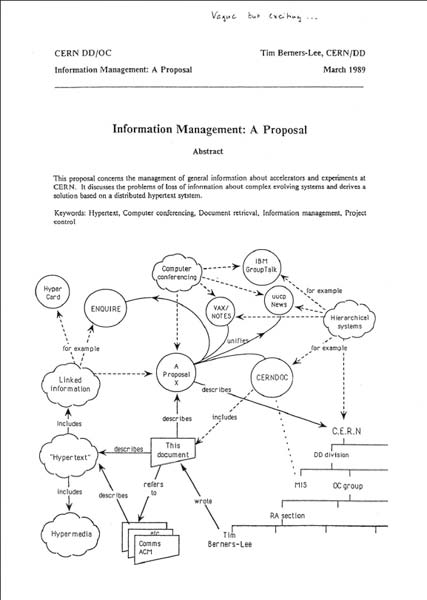

In March 1989 Tim Berners-Lee, a physicist at CERN, handed a document entitled “Information management: a proposal” to his group leader Mike Sendall. “Vague, but exciting”, were the words that Sendall wrote on the proposal, allowing Berners-Lee to continue with the project. Both were unaware that it would evolve into one of the most important communication tools ever created.

Berners-Lee returned to CERN on 13 March this year to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the birth of the World Wide Web. He was joined by several web pioneers, including Robert Cailliau and Jean-François Groff, who worked with Berners-Lee in the early days of the project, and Ben Segal, the person who brought the internet to CERN. In between reminiscing about life at CERN and the early years of the web, the four gave a demonstration of the first ever web browser running on the very same NeXT computer on which Berners-Lee wrote the original browser and server software.

The event was not only about the history of the web; it also included a short keynote speech from Berners-Lee, which was followed by a panel discussion on the future of the web. The panel members were contemporary experts who Berners-Lee believes are currently working with the web in an exciting way.

Berners-Lee’s original 1989 proposal showed how information could easily be transferred over the internet by using hypertext, the now familiar point-and-click system of navigating through information pages. The following year, Cailliau, a systems engineer, joined the project and soon became its number-one advocate.

The birth of the web

Berners-Lee’s idea was to bring together hypertext with the internet and personal computers, thereby having a single information network to help CERN physicists to share all of the computer-stored information not only at the laboratory but around the world. Hypertext would enable users to browse easily between documents on web pages that use links. Berners-Lee went on to produce a browser-editor with the goal of developing a tool to make a creative space to share and edit information and build a common hypertext. What should they call this new browser? “The Mine of Information”? “The Information Mesh”? When they settled on a name in May 1990 – before even the first piece of code had been written – it was Tim who suggested “the World Wide Web”, or “WWW”.

Development work began in earnest using NeXT computers delivered to CERN in September 1990. Info.cern.ch was the address of the world’s first web site and web server, which was running on one NeXT computer by Christmas of 1990. The first web-page address was http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html, which gave information about the WWW project. Visitors to the pages could learn more about hypertext, technical details for creating their own web page and an explanation on how to search the web for information.

Although the web began as a tool to aid particle physicists, today it is used in countless ways by the global community

To allow the web to extend, Berners-Lee’s team needed to distribute server and browser software. The NeXT systems, however, were far more advanced than the computers that many other people had at their disposal, so they set to work on a far less sophisticated piece of software for distribution. By the spring of 1991, testing was under way on a universal line-mode browser, created by Nicola Pellow, a technical student. The browser was designed to run on any computer or terminal and worked using a simple menu with numbers to provide the links. There was no mouse and no graphics, just plain text, but it allowed anyone with an internet connection to access the information on the web.

Servers began to appear in other institutions across Europe throughout 1991 and by December the first server outside the continent was installed in the US at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC). By November 1992 there were 26 servers in the world and by October 1993 the number had increased to more than 200 known web servers. In February 1993 the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign released the first version of Mosaic, which made the web easily available to ordinary PC and Macintosh computers.

The rest, as they say, is history. Although the web began as a tool to aid particle physicists, today it is used in countless ways by the global community. Today the primary purpose of household computers is not to compute but “to go on the web”.

Berners-Lee left CERN in 1994 to run the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and help to develop guidelines to ensure long-term growth of the web. So what predictions do Berners-Lee and the W3C have for the future of the web? What might it look like at the age of 30?

In his talk at the WWW@20 celebrations Berners-Lee outlined his hopes and expectations for the future: “There are currently roughly the same number of web pages as there are neurons in the human brain”. The difference, he went on to say, is that the number of web pages increases as the web grows older.

One important future development is the “Semantic Web” – a place where machines can do all of the tedious work. The concept is to create a web where machines can interpret pages like humans. It will be a “move from using a search engine to an answer engine,” explains Christian Bizer of the web-based system groups at Freie Universität Berlin. “When I search the web I don’t want to find documents, I want to find answers to my questions!” he says. If a search engine can understand a web page then it can pick out the exact answer to a question, rather than simply presenting you with a list of web pages.

As Berners-Lee put it: “The Semantic Web is a web of data. There is a lot of data that we all use every day, and it’s not part of the web. For example, I can see my bank statements on the web, and my photographs, and I can see my appointments in a calendar, but can I see my photos in a calendar to see what I was doing when I took them? Can I see bank-statement lines in a calendar? Why not? Because we don’t have a web of data. Because data is controlled by applications, and each application keeps it to itself.”

“Device independence” is a move towards a greater variety of equipment that can connect to the web. Only a few years ago, virtually the only way to access the web was through a PC or workstation. Now, mobile handsets, smart phones, PDAs, interactive television systems, voice-response systems, kiosks and even some domestic appliances can access the web.

The mobile web is one of the fastest-developing areas of web use. Already, more global web browsing is done on hand-held devices, like mobile phones, than on laptops. It is especially important in developing countries, where landlines and broadband are still rare. For example, African fishermen are using the web on old mobile phones to check the market price of fish to make sure that they arrive at the best port to sell their daily catch. The W3C is trying to create standards for browsing the web on phones and to encourage people to make the web more accessible to everyone in the world.

• The full-length webcast of the WWW@20 event is available at http://cdsweb.cern.ch/record/1167328?ln=en.