As TikTok dethrones Facebook as the most downloaded app, with 850 million downloads in 2020 alone, Craig Edwards looks at how high-energy physicists are taking advantage of the social-media phenomenon.

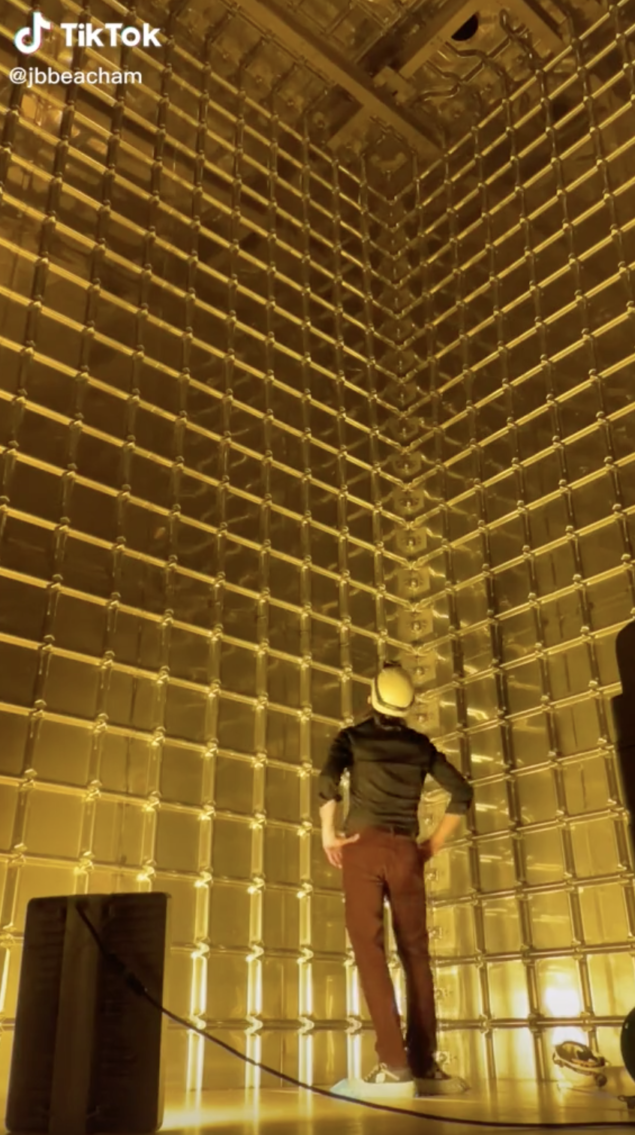

After being shown the app by her mother during lockdown, ATLAS physicist Clara Nellist downloaded TikTok and created her first two “shorts” in January this year. Jumping on a TikTok trend, the first saw her sing a CERN-themed sea shanty, while the second was an informal introduction to her page as she meandered around a park near the CERN site. Together, these two videos now total almost 600,000 views. Six months later, another ATLAS physicist, James Beacham, joined the platform, also with a quick introduction video explaining his work while using the ATLAS New Small Wheels as a backdrop. The video now has over 1.7 million views. With TikTok videos giving other social-media channels a run for their money, soon more of the high-energy physics community may want to join the rising media tide.

Surfing the wave

From blogs in the early 2000s through to Twitter and YouTube today, user-generated ‘Web 2.0’ platforms have allowed scientists to discuss their work and share their excitement directly. In the case of particle physics, researchers and their labs have never been within closer reach to the public, with a tour of the Large Hadron Collider always just a few clicks away. In 2005, as blogs were mushrooming, CERN and other players in particle physics joined forces to create Quantum Diaries. As the popularity of blogs began to dwindle towards the late noughties, CERN hopped on the next wave, joining YouTube in 2007 and Twitter in 2008 – at a time when public interest in the LHC was at its peak. CERN’s Twitter account currently boasts an impressive 2.5 million followers.

While joining later than some other laboratories, Fermilab caught onto a winning formula on YouTube, with physicist Don Lincoln fronting a long-standing educational series that began in 2011 and still runs today, attracting millions of views. Most major particle-physics laboratories also have a presence on Facebook and Instagram, with CERN joining the platforms in 2011 and 2014 respectively, not to mention LinkedIn, where CERN also possesses a significant following.

Particle physics laboratories are yet to launch themselves on TikTok. But that hasn’t stopped others from creating videos about particle physics, and not always “on message”. Type ‘CERN’ into the TikTok search bar and you are met with almost a 50/50 mix of informative videos and conspiracy theories – and even then, some of the former are merely debunking the latter. Is it time for institutions to get in on the trend?

Rising to the moment

Nellist, who has 123,000 followers on TikTok after less than nine months on the site, believes that it’s the human aspect and uniqueness of her content that has caused the quick success. “I started because I wanted to humanise science – people don’t realise that normal humans work at CERN. When I started there was nobody else at CERN doing it.” Beacham also uses CERN as a way of capturing attention, as illustrated in his weekly livestreams to his 230,000 followers. “If someone is scrolling and sees someone sitting in a DUNE cryostat discussing science, they’re going to stop and check it out,” he says. Beacham sees himself as a filmmaker, rather than a “TikTok-er”, and flexes his bachelor’s degree in film studies with longer form videos that take him across the CERN campus. “There is a desire on TikTok to know about CERN,” he says.

TikTok is different to other social-media platforms in several ways, one being incompatibility. While a single piece of media such as a video can be shared across YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, etc., this same media would not work on TikTok. Videos can also only be a maximum of three minutes, although the majority are shorter. This encourages concise productions, with a lot of information put across in a short period of time. Arguably the biggest difference is that TikTok insists that every video is in portrait mode – creating a feeling of authenticity and an intimate environment. YouTube and Instagram are now following suit with their portrait-mode ‘YouTube Shorts’, and ‘Instagram Reels’ respectively, with CERN already using the latter to create quick and informative clips that have attracted large audiences.

Nellist and Beacham, both engaging physicists in their own right who the viewer feels they can trust, create a perfect blend for TikTok. While there are some topics that will always generate more interest, they have a core audience that consistently returns for all videos. This gives a strong sense of editorial freedom, says Nellist. “While it is important to be aware of views, I get to make what I want.”

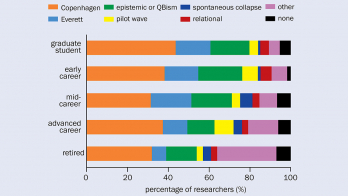

Changing demographics

When CERN joined Twitter in 2008, says James Gillies, head of CERN communications at the time, young people were a key factor as CERN tried to maximise its digital footprint. But things have changed since then. It is estimated that there are over 1 billion active TikTok users per month, and according to data firm Statista, in the US almost 50% of them are aged 30 and under, with other reports stating that up to 32.5% of users are between the ages of 10 and 19. Statista also estimates that only 24% of today’s Twitter users are under 25 – the so-called ‘Gen-Z’ who will fund and possibly work on future colliders.

If you want to lead the conversation, you have to be part of it

James Gillies

Another reason for CERN to enter the Twitter-verse (and which facilitated the creation of Quantum Diaries), says Gillies, was to allow CERN to take their communication into their own hands. Although Nellist and Beacham are already encouraging this discussion on TikTok, they are not official CERN communication channels. Were they to decide to stop or talk about different topics, it would be hard to find any positive high-energy physics discussions on the most popular app on the planet.

Whilst Nellist believes CERN should be joining the platform, she urges that someone “who knows about it” should be dedicated to creating the content, as it is obvious to TikTok audiences when someone doesn’t understand it. Beacham states, “humans don’t respond to ideas as much as they respond to people.” Creators have their own unique styles and personalities that the viewers enjoy. So, if a large institution were to join, how would it create this personal environment?

The ATLAS experiment is currently the only particle-physics experiment to be found on the platform. The content is less face-to-face and more focused on showing the detector and how it works – similar in style to a CERN Instagram story. Despite being active for a similar amount of time as Nellist and Beacham, however, the account has significantly fewer followers. Nellist, who runs the ATLAS TikTok account, thinks there is room for both personal and institutional creators on the platform, though the content should be different. Beacham agrees, stating that it should show individual scientists expressing information in an off-the-cuff way. “There is a huge opportunity to do something great with it, there are thousands of things you could do. There are amazing visuals that CERN is capable of creating that can grab a viewer’s attention.”

Keeping up

There may be some who scoff at the idea of CERN joining a platform that has a public image of creating dance crazes rather than educational content. It is easy to forget that when first established, YouTube was seen as the place for funny cat videos, while Twitter was viewed as an unnecessary platform for people to tell others what they had for breakfast. Now these two platforms are the only reason some may know CERN exists, and unfortunately, not always for the right reasons.

Social media gives physicists and laboratories the opportunity to contact and influence audiences more directly than traditional channels. The challenge is to keep up with the pace of change. It’s clearly early days for a platform that only took off in 2018. Even NASA, which has the largest number of social-media followers of any scientific institution, is yet to launch an official TikTok channel. But, says Gillies, “If you want to lead the conversation, you have to be part of it.”