On 13 February 2023, strings of photodetectors anchored to the seabed off the coast of Sicily detected the most energetic neutrino ever observed, smashing previous records. Embargoed until the publication of a paper in Nature last month, the KM3NeT collaboration believes their observation may have originated in a novel cosmic accelerator, or may even be the first detection of a “cosmogenic” neutrino.

“This event certainly comes as a surprise,” says KM3NeT spokesperson Paul de Jong (Nikhef). “Our measurement converted into a flux exceeds the limits set by IceCube and the Pierre Auger Observatory. If it is a statistical fluctuation, it would correspond to an upward fluctuation at the 2.2σ level. That is unlikely, but not impossible.” With an estimated energy of a remarkable 220 PeV, the neutrino observed by KM3NeT surpasses IceCube’s record by almost a factor of 30.

The existence of ultra-high-energy cosmic neutrinos has been theorised since the 1960s, when astrophysicists began to conceive ways that extreme astrophysical environments could generate particles with very high energies. At about the same time, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered “cosmic microwave background” (CMB) photons emitted in the era of recombination, when the primordial plasma cooled down and the universe became electrically neutral. Cosmogenic neutrinos were soon hypothesised to result from ultra-high-energy cosmic rays interacting with the CMB. They are expected to have energies above 100 PeV (1017 eV), however, their abundance is uncertain as it depends on cosmic rays, whose sources are still cloaked in intrigue (CERN Courier July/August 2024 p24).

A window to extreme events

But how might they be detected? In this regard, neutrinos present a dichotomy: though outnumbered in the cosmos only by photons, they are notoriously elusive. However, it is precisely their weakly interacting nature that makes them ideal for investigating the most extreme regions of the universe. Cosmic neutrinos travel vast cosmic distances without being scattered or absorbed, providing a direct window into their origins, and enabling scientists to study phenomena such as black-hole jets and neutron-star mergers. Such extreme astrophysical sources test the limits of the Standard Model at energy scales many times higher than is possible in terrestrial particle accelerators.

Because they are so weakly interacting, studying cosmic neutrinos requires giant detectors. Today, three large-scale neutrino telescopes are in operation: IceCube, in Antarctica; KM3NeT, under construction deep in the Mediterranean Sea; and Baikal–GVD, under construction in Lake Baikal in southern Siberia. So far, IceCube, whose construction was completed over 10 years ago, has enabled significant advancements in cosmic-neutrino physics, including the first observation of the Glashow resonance, wherein a 6 PeV electron antineutrino interacts with an electron in the ice sheet to form an on-shell W boson, and the discovery of neutrinos emitted by “active galaxies” powered by a supermassive black hole accreting matter. The previous record-holder for the highest recorded neutrino energy, IceCube has also searched for cosmogenic neutrinos but has not yet observed neutrino candidates above 10 PeV.

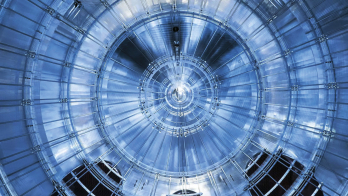

Its new northern-hemisphere colleague, KM3NeT, consists of two subdetectors: ORCA, designed to study neutrino properties, and ARCA, which made this detection, designed to detect high-energy cosmic neutrinos and find their astronomical counterparts. Its deep-sea arrays of optical sensors detect Cherenkov light emitted by charged particles created when a neutrino interacts with a quark or electron in the water. At the time of the 2023 event, ARCA comprised 21 vertical detection units, each around 700 m in length. Its location 3.5 km deep under the sea reduces background noise, and its sparse set up over one cubic kilometre optimises the detector for neutrinos of higher energies.

The event that KM3NeT observed in 2023 is thought to be a single muon created by the charged-current interaction of an ultra-high-energy muon neutrino. The muon then crossed horizontally through the entire ARCA detector, emitting Cherenkov light that was picked up by a third of its active sensors. “If it entered the sea as a muon, it would have travelled some 300 km water-equivalent in water or rock, which is impossible,” explains de Jong. “It is most likely the result of a muon neutrino interacting with sea water some distance from the detector.”

The network will improve the chances of detecting new neutrino sources

The best estimate for the neutrino energy of 220 PeV hides substantial uncertainties, given the unknown interaction point and the need to correct for an undetected hadronic shower. The collaboration expects the true value to lie between 110 and 790 PeV with 68% confidence. “The neutrino energy spectrum is steeply falling, so there is a tug-of-war between two effects,” explains de Jong. “Low-energy neutrinos must give a relatively large fraction of their energy to the muon and interact close to the detector, but they are numerous; high-energy neutrinos can interact further away, and give a smaller fraction of their energy to the muon, but they are rare.”

More data is needed to understand the sources of ultra-high-energy neutrinos such as that observed by KM3NeT, where construction has continued in the two years since this remarkable early detection. So far, 33 of 230 ARCA detection units and 24 of 115 ORCA detection units have been installed. Once construction is complete, likely by the end of the decade, KM3NeT will be similar in size to IceCube.

“Once KM3NeT and Baikal–GVD are fully constructed, we will have three large-scale neutrino telescopes of about the same size in operation around the world,” adds Mauricio Bustamante, theoretical astroparticle physicist at the Niels Bohr Institute of the University of Copenhagen. “This expanded network will monitor the full sky with nearly equal sensitivity in any direction, improving the chances of detecting new neutrino sources, including faint ones in new regions of the sky.”

Further reading

The KM3NeT Collab. 2025 Nature 638 376.