Results from a new survey show the important impact of working at CERN on an individual’s career.

Since the advent of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), CERN has been recognised as the world’s leading laboratory for experimental particle physics. More than 10,000 people work at CERN on a daily basis. The majority are members of universities and other institutions worldwide, and many are young students and postdocs. The experience of working at CERN therefore plays an important role in their careers, be it in high-energy physics or a different domain.

The value of education

In 2016 the CERN management appointed a study group to collect information about the careers of students who have completed their thesis studies in one of the four LHC experiments. Similar studies were carried out in the past, also including people working on the former LEP experiments, and were mainly based on questionnaires sent to the team leaders of the various collaborator institutes. The latest study collected a larger and more complete sample of up-to-date information from all the experiments, with the aim of addressing young physicists who have left the field. This allows a quantitative measurement of the value of the education and skills acquired at CERN in finding jobs in other domains, which is of prime importance to evaluate the impact and role of CERN’s culture.

Following an initial online questionnaire with 282 respondents, the results were presented to the CERN Council in December 2016. The experience demonstrated the potential for collecting information from a wider population and also to deepen and customise the questions. Consequently, it was decided to enlarge the study to all persons who have been or are still involved with CERN, without any particular restrictions. Two distinct communities were polled with separate questionnaires: past and current CERN users (mainly experimentalists at any stage of their career), and theorists who had collaborated with the CERN theory department. The questionnaires were opened for a period of about four months and attracted 2692 and 167 participants from the experimental and theoretical communities, respectively. A total of 84 nationalities were represented, with German, Italian and US nationals making

up around half, and the distribution of participants by experiments was: ATLAS (994); CMS (977); LHCb (268) ALICE (102); and “other” (87), which mainly included members of the NA62 collaboration.

The questionnaires addressed various professional and sociological aspects: age, nationality, education, domicile and working place, time spent at CERN, acquired expertise, current position, and satisfaction with the CERN environment. Additional points were specific to those who are no longer CERN users, in relation to their current situation and type of activity. The analysis revealed some interesting trends.

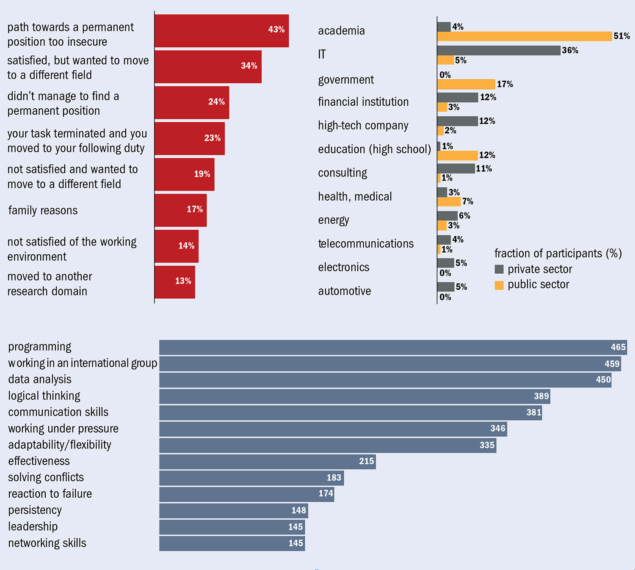

For experimentalists, the CERN environment and working experience is considered as satisfactory or very satisfactory by 82% of participants, which is evenly distributed across nationalities. In 70% of cases, people who left high-energy physics mainly did so because of the long and uncertain path for obtaining a permanent position. Other reasons for leaving the field, although quoted by a lower percentage of participants, were: interest in other domains; lack of satisfaction at work; and family reasons. The majority of participants (63%) who left high-energy physics are currently working in the private sector, often in information technology, advanced technologies and finance domains, where they occupy a wide range of positions and responsibilities. Those in the public sector are mainly involved in academia or education.

For persons who left the field, several skills developed during their experience at CERN are considered important in their current work. The overall satisfaction of participants with their current position was high or very high for 78% of respondents, while 70% of respondents considered CERN’s impact on finding a job outside high-energy physics as positive or very positive. CERN’s services and networks, however, are not found to be very effective in helping finding a new job – a situation that is being addressed, for example, by the recently launched CERN alumni programme.

Theorists participating in the second questionnaire mainly have permanent or tenure-track positions. A large majority of them spent time at CERN’s theory department with short- or medium-term contracts, and this experience seems to improve participants’ careers when leaving CERN for a national institution. On average, about 35% of a theorist’s scientific publications originate from collaborations started at CERN, and a large fraction of theorists (96%) declared that they are satisfied or highly satisfied with their experience at CERN.

Conclusions

As with all such surveys, there is an inherent risk of bias due to the formulation of the questions and the number and type of participants. In practice, only between 20 and 30% of the targeted populations responded, depending on the addressed community, which means the results of the poll cannot be considered as representative of the whole CERN population. Nevertheless, it is clear that the impact of CERN on people’s careers is considered by a large majority of the people polled to be mostly positive, with some areas for improvement such as training and supporting the careers of those who choose to leave CERN and high-energy physics.

In the future this study could be made more significant by collecting similar information on larger samples of people, especially former CERN users. In this respect, the CERN alumni programme could help build a continuously updated database of current and former CERN users and also provide more support for people who decide to leave high-energy physics.

The final results of the survey, mostly in terms of statistical plots, together with a detailed description of the methods used to collect and analyse all the data, have been documented in a CERN Yellow Report, and will also be made available through a dedicated web page.