How Gilberto Bernardini helped to inspire Leon Lederman’s rediscovered enthusiasm for experimental physics.

As a grad student at Columbia around 1950, I had the rare opportunity of meeting Albert Einstein. We were instructed to sit on a bench that would intersect Einstein’s path to lunch at his Princeton home. A fellow student and I sprang up when Einstein came by, accompanied by his assistant who asked if he would like to meet some students.

“Yah,” the professor said and addressed my colleague, “Vot are you studying?”

“I’m doing a thesis on quantum theory.”

“Ach!” said Einstein, “A vaste of time!” He turned to me: “And vot are you doing?”

I was more confident: “I’m studying experimentally the properties of pions.”

“Pions, pions! Ach, vee don’t understand de electron! Vy bother mit pions? Vell, good luck boys!”

So, in less than 30 seconds, the Great Physicist had demolished two of the brightest – and best-looking – young physics students. But we were on cloud nine. We had met the greatest scientist who ever lived!

Some years before this memorable event, I had recently been discharged from the US army, having been drafted three years earlier to help General Eisenhower with a problem he had in Europe. It was called World War II. Our troop ship docked at the Battery and, having had a successful poker-driven ocean crossing, I taxied to Columbia University and registered as a physics grad student for the fall semester.

I was filled with enthusiasm to resume my study of physics but also exhausted by three years of mostly mindless military service. Things quickly degenerated towards disaster. I had indeed forgotten simple equations, how to study and, most crucially, forgotten the joy that I had found in my college physics classes. Full-time, intense study did not seem to help. I failed the crucial qualifying exam, twice. I was ready to quit.

I had been assigned a lab on the 10th floor of the Pupin Physics Building where I had been given the job of making a cloud chamber work. This was a 12-inch cylinder of glass and plastic filled with N2 alcohol vapour. This device can render the path of a nuclear particle visible since the “wake” of the intruder particle produces a trail of disturbed atoms. This encourages alcohol vapour to coalesce from vapour to drops of liquid. A flash photograph then captures a record of the nuclear particle – much like the vapour trail of a jet airliner. But as much as I tried, my cloud chamber produced no tracks, only a cloud of white smoke. This failure, added to the failed tests and joyless lectures, brought me misery and to the point of quitting. I decided to take the PhD qualifying test once more and took two weeks to study.

After the test (I felt only slightly better), I returned to the lab to find a janitor mopping the wire-strewn floor and singing an Italian operatic tune. As I entered, the guy shouted something in Italian and offered a handshake.

I said, “Okay, but be careful. The wires are carrying a high current and your wet mop may produce a short circuit.” He stared cluelessly and, in total disgust, I walked out in the hall to wait for the guy to leave.

In the hall, there was the department chairman. “We have a new, dumb janitor, huh?” I said.

“New? No, wait! You mean the guy in your lab?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s no janitor, dummy, that’s Professor Gilberto Bernardini, a world-famous Italian cosmic-ray expert whom I invited to spend a year here to help you in your research.”

“Oh, my God!” I gasped and rushed in to repair my damage.

Over time, Bernardini and I learnt how to communicate and I began to watch Gilberto. There was his habit of entering a dark room, pushing the light switch: light. Pushing it again: off. On, off five or six times. Each time there would be a loud “fantastico!” Why? He seemed to have this remarkable sense of wonder about simple things.

Then the cloud chamber.

Gilberto: “Wat’s dat wire in de middle?”

Leon: “That’s carrying the radioactive source.”

Gilberto: “Tayk id oud.”

Leon: “It makes tracks.”

Gilberto: “Tayk id oud.”

After a few minutes, tracks appeared. My source had been far too radioactive for the chamber! Now we had a success.

But this was only the beginning of my learning from Bernardini. Next, we constructed a kind of Geiger counter. We machined, soldered, polished, flushed with clean argon gas and watched the oscilloscope. Soon we had tracks.

Bernardini went nuts. “Izza counting!” he screamed. Half of my height and weight, he lifted me and danced me round the lab to the music of Bernardini’s sense of wonder. He explained: “Dese particles, cosmic ray, come from billions of miles away to say buonjourno to us on de tenth floor of Pupin Physics Building. Izza beautiful! So little particle, so long da trip.”

So, through Bernardini, I began to recover my love of physics, of searching for simplicity and elegance of how the world works. I recovered academically and eventually graduated to a professorship.

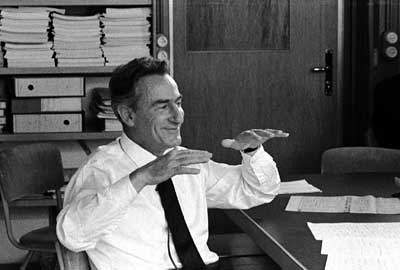

Image credit: BNL.

Gilberto warned me about what happened next. Some years into my Columbia career, I was on the night shift of an experiment. It was 3 a.m.; I had checked that all the apparatus was working when one computer began to beep out of tune. I tuned it to scan the data and – there it was, the most spectacularly beautiful track I had ever seen. What I was seeing was a muon entering from a thin metal plate and passing through 10 more plates. A muon! The only explanation was that a neutrino had generated this track – a muon neutrino! Its implications dawned on me – two neutrinos – this would change how we taught physics; this would make headlines from Scotland to Argentina… My palms were wet, my breathing became difficult. I tested everything, but only confirmed the discovery. At 4 a.m. I telephoned Gilberto, who was then visiting in Illinois. His wonderful “fantastico!” had been Americanized and when I told him what we had found, out came “Holy shit!”

Gilberto knew everybody. Fermi, Amaldi, Bohr, Schrödinger, … Einstein. At a meeting (after receiving my PhD), we heard Einstein describe relativity: “scarcely anyone who truly understands this theory can escape its magic.”

As Keats said: “Truth is Beauty and Beauty Truth. That is all ye know of Earth.” And Plato: “The soul is awestruck and shudders at the sight of the beautiful.”

Some years later, Gilberto and my wife, Ellen, were in Sweden to help me receive the Nobel prize. Gilberto’s “fantastico!” was ubiquitous. And I said to Ellen, “Did you ever in your wildest dreams imagine that we would be in Sweden dining with the king and queen?” Ellen, as ever sceptical, said, “You were never in my wildest dreams!”

Science has always been and will continue to be a mixture of 96% frustration and (if lucky) 4% elation. But having a Bernardini to restore that crucial sense of wonder sure helps.