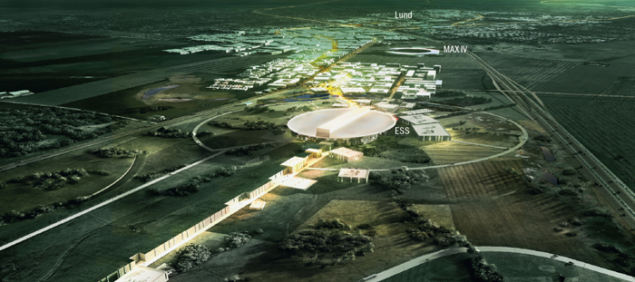

Image credit: ESS/Team Henning Larsen Architects.

Today, neutron research takes place either at nuclear reactors or at accelerator-based sources. For a long time, reactors have been the most powerful sources in terms of integrated neutron flux. Nevertheless, accelerator-based sources, which usually have a pulsed structure (SINQ at PSI being a notable exception), can provide a peak flux during the pulse that is much higher than at a reactor. The European Spallation Source (ESS) – currently under construction in Lund – will be based on a proton linac that is powerful enough to give a higher integrated useful flux than any research reactor. It will be the world’s most powerful facility for research using neutron beams, when it comes into full operation early in the next decade. Although driven by the neutron-scattering community, the project will also offer the opportunity for experiments in fundamental physics, and there are plans to use the huge amount of neutrinos produced at the spallation target for neutrino physics.

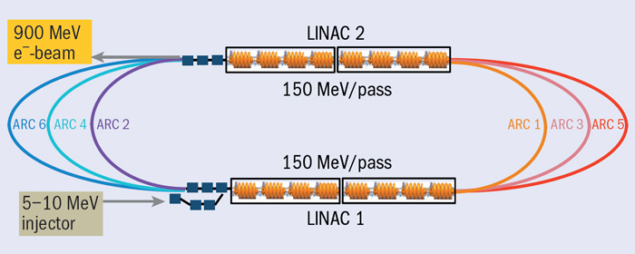

The story of the ESS goes back to the early 1990s, with a proposal for a 10 MW linear accelerator, a double compressor ring and two target stations. The aim was for an H– linac to deliver alternate pulses to a long-pulse target station and to the compressor rings. The long-pulse target was to receive 2-ms long pulses from the linac, while multiturn injection into the rings would provide a compression factor of 800 and allow a single turn of 1.4 μs to be extracted to the short-pulse target station.

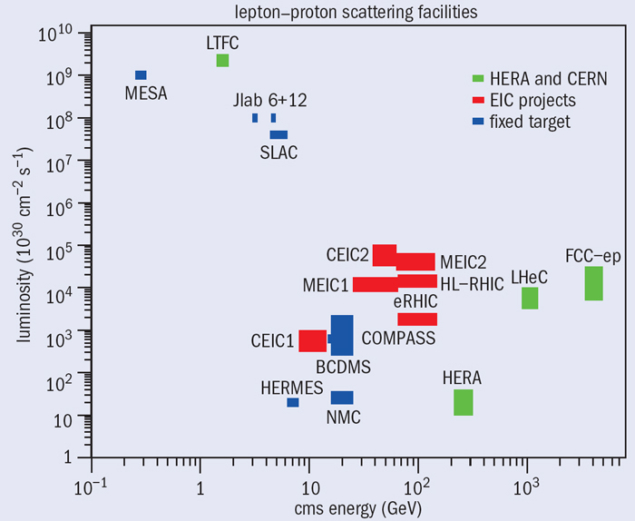

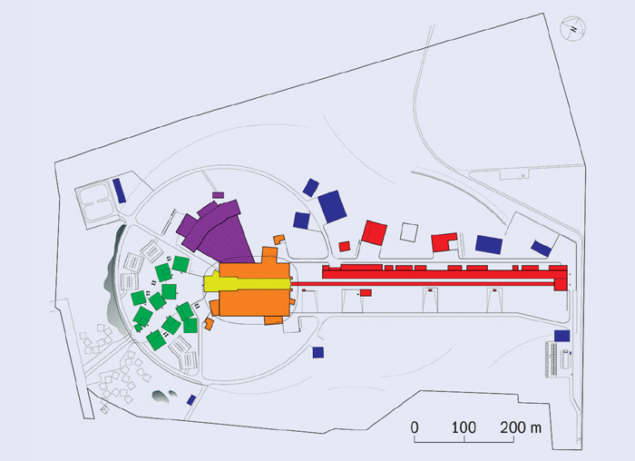

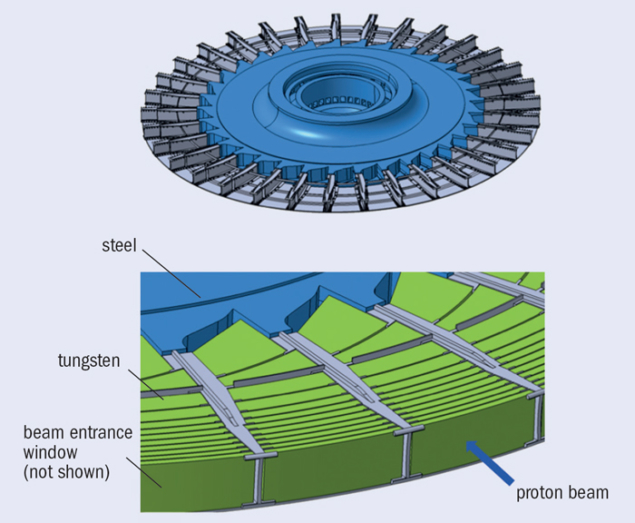

This proposal was not funded, however, and after a short hiatus, new initiatives to build the ESS appeared in several European countries. By 2009, three candidates remained: Hungary (Debrecen), Spain (Bilbao) and Scandinavia (Lund). The decision to locate the ESS near Lund was taken in Brussels in May 2009, after a competitive process facilitated by the European Strategy Forum for Research Infrastructures and the Czech Republic’s Ministry of Research during its period of presidency of the European Union. In this new incarnation, the proposal was to build a facility with a single long-pulse target powered by a 5 MW superconducting proton linac (figure 1). The neutrons will be released from a rotating tungsten target hit by 2 GeV protons emerging from this superconducting linac, with its unprecedented average beam power.

Neutrons have properties that make them indispensable as tools in modern research. They have wavelengths and energies such that objects can be studied with a spatial resolution between 10–10 m and 10–2 m, and with a time resolution between 10–12 s and 1 s. These length- and time-scales are relevant for dynamic processes in bio-molecules, pharmaceuticals, polymers, catalysts and many types of condensed matter. In addition, neutrons interact quite weakly with matter, so they can penetrate large objects, allowing the study of materials surrounded by vacuum chambers, cryostats, magnets or other experimental equipment. Moreover, in contrast to the scattering of light, neutrons interact with atomic nuclei, so that neutron scattering is sensitive to isotope effects. As an extra bonus, neutrons also have a magnetic moment, which makes them a unique probe for investigations of magnetism.

Neutron scattering also has limitations. One of these is that neutron sources are weak compared with sources of light or of electrons. Neutrons are not created, but are “mined” from atomic nuclei where they are tightly bound, and it costs a significant amount of energy to extract them. Photons, on the other hand, can be created in large amounts, for instance in synchrotron light sources. Experiments at light sources can therefore be more sensitive in many respects than those at a neutron source. For this reason, the siting of ESS next to MAX IV – the next-generation synchrotron radiation facility currently being built on the north-eastern outskirts of Lund – is important. Thanks to its pioneering magnet technology, MAX IV will be able to produce light with higher brilliance than at any other synchrotron light source, while the ESS will be the most powerful neutron source in the world.

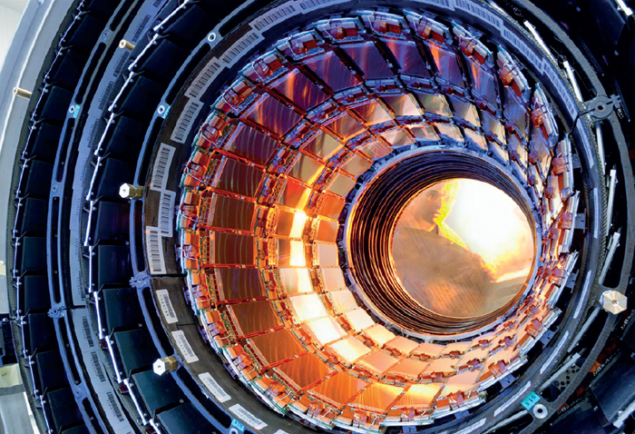

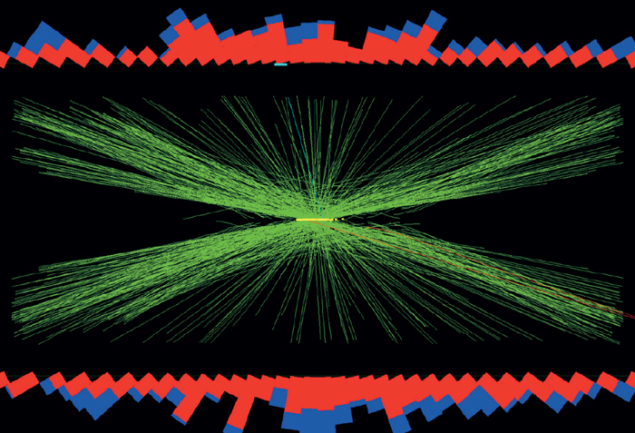

The ESS will provide unique opportunities for experiments in fundamental neutron physics that require the highest possible integrated neutron flux. A particularly notable example is the proposed search for neutron–antineutron oscillations. The high neutron intensity at the ESS will allow sufficient precision to make neutron experiments complementary to efforts in particle physics at the highest energies, for example at the LHC. The importance of the low-energy, precision “frontier” has been recognized widely (Raidal et al. 2008 and Hewett et al. 2012), and an increasing number of theoretical studies have exploited this complementarity and highlighted the need for further, more precise experimental input (Cigliano and Ramsey-Musolf 2013).

In addition, the construction of a proton accelerator at the high-intensity frontier opens possibilities for investigations of neutrino oscillations. A collaboration is being formed by Tord Ekelöf and Marcos Dracos to study a measurement of CP violation in neutrinos using the ESS together with a large underground water Cherenkov detector (Baussen et al. 2013).

The main components

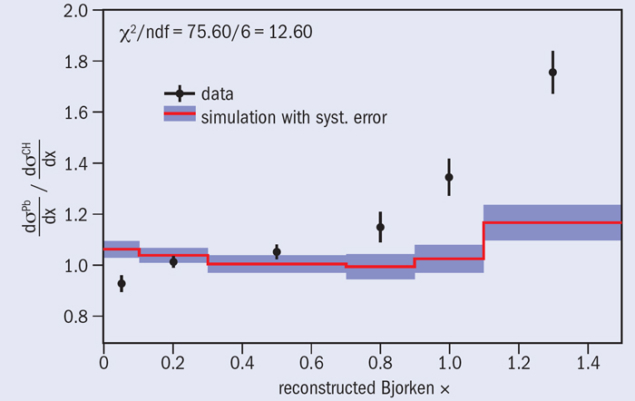

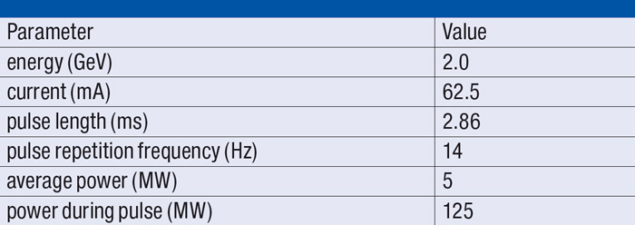

The number of neutrons produced at the tungsten target will be proportional to the beam current, and because the total production cross-section in the range of proton energies relevant for the ESS is approximately linear with energy, the total flux of neutrons from the target is nearly proportional to the beam power. Given a power of 5 MW, beam parameters have been optimized with respect to cost and reliability, while user requirements have dictated the pulse structure. Table 1 shows the resulting top-level parameters for the accelerator.

The linac will have a normal-conducting front end, followed by three families of superconducting cavities, before a high-energy beam transport brings the protons to the spallation target. Because the ESS is a long-pulse source, it can use protons rather than the H– ions needed for efficient injection into the accumulator ring of a short-pulse source.

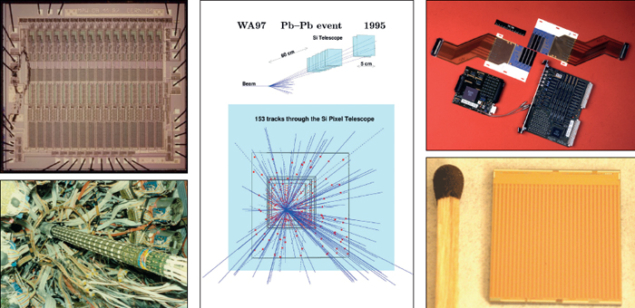

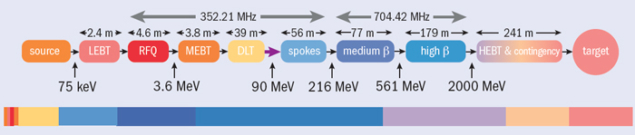

Figure 2 illustrates the different sections of the linac. In addition to the ion source on a 75 kV platform, the front end consists of a low-energy beam transport (LEBT), a radio-frequency quadrupole that accelerates to 3.6 MeV, a medium-energy beam transport (MEBT) and a drift-tube linac (DTL) that takes the beam to 90 MeV.

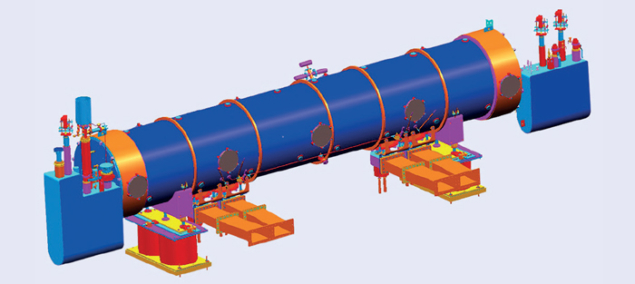

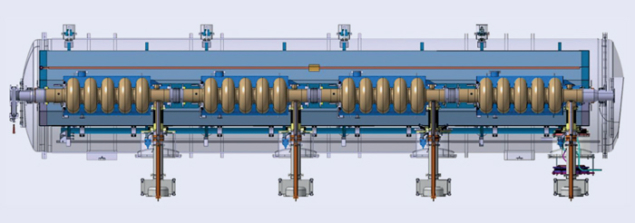

The superconducting linac, operating with superfluid helium at 2 K, starts with a section of double-spoke cavities having an optimum beta of 0.50. The protons are accelerated to 216 MeV in 13 cryomodules, each of which has two double-spoke cavities. Medium- and high-beta elliptical cavities follow, with geometric beta values of 0.67 and 0.92. The medium-beta cavities have six cells, the high-betas have five cells. In this way, the two cavity types have almost the same length, so that cryomodules of the same overall design can be used in both cases to house four cavities. Figure 3 shows a preliminary design of a high-beta cryomodule, with its four five-cell cavities and power couplers extending downwards.

Nine medium-beta cryomodules accelerate the beam to 516 MeV, and the final 2 GeV is reached with 21 high-beta modules. The normal-conducting acceleration structures and the spoke cavities run at 352.21 MHz, while the elliptical cavities operate at twice the frequency, 704.42 MHz. After reaching their full energy, the protons are brought to the target by the high-energy beam transport (HEBT), which includes rastering magnets that produce a 160 × 60 mm rectangular footprint on the target wheel.

The design of the proton accelerator – as with the other components of the ESS – has been carried out by a European collaboration. The ion source and LEBT have been designed by INFN Catania, the RFQ by CEA Saclay, the MEBT by ESS-Bilbao, the DTL by INFN Legnaro, the spoke section by IPN Orsay, the elliptical sections again by CEA Saclay, and the HEBT by ISA Århus. During the design phase, additional collaboration partners included the universities of Uppsala, Lund and Huddersfield, NCBJ Świerk, DESY and CERN. Now the collaboration is being extended further for the construction phase.

A major cost driver of the ESS accelerator centres on the RF sources. Klystrons provide the standard solution for high output power at the frequencies relevant to the ESS. For the lower power of the spoke cavities, tetrodes are an option, but solid-state amplifiers have not been excluded completely, even though the required peak powers have not been demonstrated yet. Inductive output tubes (IOTs) are an interesting option for the elliptical cavities, in particular for the high-beta cavities, where the staged installation of the linac still allows for a few years of studies. While IOTs are more efficient and take up less space than klystrons, they are not yet available for the peak powers required, but the ESS is funding the development of higher-power IOTs in industry.

Neutron production

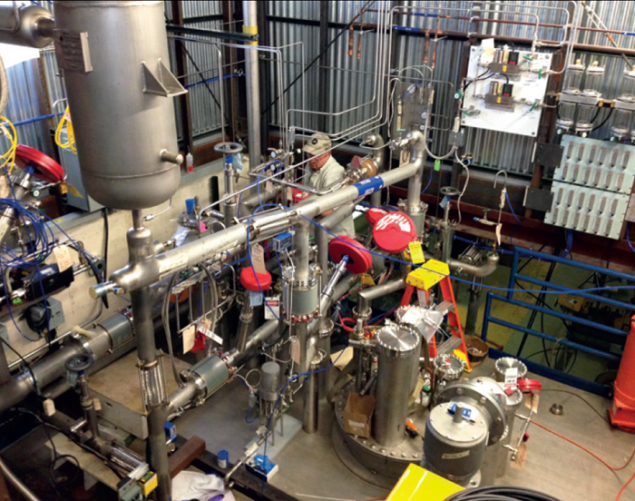

The ESS will use a rotating, gas-cooled tungsten target rather than, for instance, the liquid-mercury targets used at the Spallation Neutron Source in the US and in the neutron source at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex. As well as avoiding environmental issues that arise with mercury, the rotating tungsten target will require the least amount of development effort. It also has good thermal and mechanical properties, excellent safety characteristics and high neutron production.

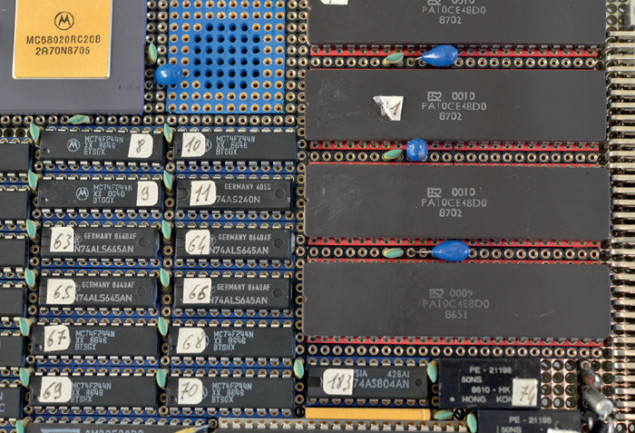

Image credit: Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

The target wheel has a diameter of 2.5 m and consists of tungsten elements in a steel frame (figure 4). The tungsten elements are separated by cooling channels for the helium gas. The wheel rotates at 25 rpm synchronized with the beam pulses, so that consecutive pulses hit adjacent tungsten elements. An important design criterion is that the heat generated by radioactive decay after the beam has been switched off must not damage the target, even if all active cooling systems fail.

With the ESS beam parameters, every proton generates about 80 neutrons. Most of them are emitted with energies of millions of electron volts, while most experiments need cold neutrons, from room temperature down to some tens of kelvins. For this reason, the neutrons are slowed down in moderators containing water at room temperature and super-critical hydrogen at 13–20 K before being guided to the experimental stations, which are known as instruments. The construction budget contains 22 such instruments, including one devoted to fundamental physics with neutrons.

The ESS is an international European collaboration where 17 European countries (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Iceland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, France, the UK, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Switzerland, Italy and Spain) have signed letters of intent. Negotiations are now taking place to distribute the costs between these countries.

The project has now moved into the construction phase, with ground breaking planned for summer this year.

Sweden and Denmark have been hosting the ESS since the site decision, and a large fraction of the design study that started then was financed by Sweden and Denmark. The project has now moved into the construction phase, with ground breaking planned for summer this year.

According to the current project plans, the accelerator up to and including the medium-beta section will be ready by the middle of 2019. Then, the first protons will be sent to the target and the first neutrons will reach the instruments. During the following few years, the high-beta cryomodules will be installed, such that the full 5 MW beam power will be reached in 2022.

The neutron instruments will be built in parallel. Around 40 concepts are being developed at different laboratories in Europe, and the 22 instruments of the complete ESS project will be chosen in a peer-reviewed selection process. Three of these will have been installed in time for the first neutrons. The rest will gradually come on line during the following years, so that all will have been installed by 2025.

The construction budget of ESS amounts to €1,843 million, half of which comes from Sweden, Denmark and Norway. The annual operating costs are estimated to be €140 million, and the cost for decommissioning the ESS after 40 years has been included in the budget. The hope, however, is that the scientific environment that will grow up around ESS and MAX IV – and within the Science Village Scandinavia to be located in the same area – will last longer than that.