The 2024 Aspen Winter Conference, The Future of High Energy Physics: A New Generation, A New Vision, attracted 50 early-career researchers (ECRs) from across the world to the Aspen Center for Physics, 8000 feet above sea level in the Colorado Rockies, from 24 to 29 March. The conference built on the many new ideas that arose from the recent Snowmass process of the US particle physics community (CERN Courier January/February 2024 p7). The conference sought to highlight the role of ECRs in realising bold long-term visions for the field, covering theoretical questions, the experimental vision for the next 50 years and the technologies required to make it a reality. Students, postdocs and junior faculty are often the drivers of new ideas in science. Helping them transition new ideas to the mainstream requires enthusiasm, community support and time.

Crossing frontiers

85% of the matter in the universe at most minimally interacts with the electromagnetic force but provided the gravitational seed for large-scale structure formation in the early universe. Hugh Lippincott (University of California, Santa Barbara) summarised cross-frontier searches. Pursuing all possible scenarios via direct detection will require scaling up existing technology and developing new technologies such as quantum sensors to probe lighter dark-matter candidates. On the one hand, the 60 to 80 tonne “XLZD” liquid xenon detector will merge the expertise of the XENONnT, LUX-ZEPLIN and DARWIN collaborations; on the low-mass side, Reina Maruyama (Yale) discussed the ALPHA and HAYSTAC haloscopes, which seek to convert axions into photons in highly tuned resonant cavities. Indirect detection and collider experiments will also play an important role in closing in on minimal dark-matter models.

Delegates expressed a sense of urgency to probe higher energies. Cari Cesarotti (MIT) advocated R&D towards a future muon collider, arguing that muons offer a clean and power-efficient route to the 10 TeV scale and above. Recently, experts have estimated that challenges due to the finite muon lifetime could be overcome on a 20-year technically limited timeline. Both CERN and China have proposed building 100 km-circumference tunnels, initially hosting an electron–positron collider followed by a 100 TeV hadron machine, however, the timeline suggests that almost all of the conference attendees would be retired before hadron collisions come online. Elliot Lipeles (Pennsylvania) proposed skipping the electron-positron stage and immediately pursuing an intermediate-energy hadron collider: existing magnets in a 100 km tunnel could produce 37 TeV collisions, advancing measurements of the Higgs self-coupling and electroweak phase transition, dark matter and its mediators, and naturalness.

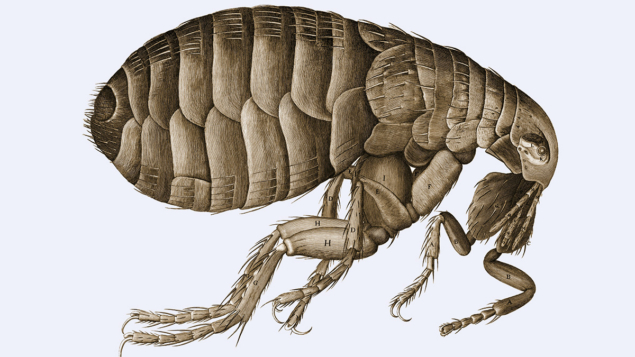

The energy, intensity and cosmic frontiers of particle physics target deeply connected questions

Neutrinos were discussed at length. Georgia Karagiorgi (Columbia University) argued that three short-baseline anomalies remain, potentially hinting at additional sterile neutrinos or dark-sector portals. Julieta Gruszko (North Carolina at Chapel Hill) presented an exciting future for experiments that seek to discern the fundamental nature of neutrinos. A new tonne-scale generation of detectors comprising LEGEND1000, nEXO and CUPID may succeed in confirming the Majorana nature of the neutrino if they observe neutrinoless double beta decay.

Talks on the importance of science communication and education provoked a great deal of discussion. Ethan Siegal, host of popular podcast “Starts with a Bang” spoke on public outreach, Kevin Pedro (Fermilab) on advocacy with policymakers in Washington, DC, and Roger Freedman (University of California Santa Barbara) on educating the next generation of physicists. In public programming, Nausheen Shah (Wayne State) was the guest speaker at a screening of Hidden Figures, the inspiring true story of the black women who helped the US win the space race, and Philip Chang (University of California San Diego) lectured on “An Invitation to Imagine Something from Nothing”.

The energy, intensity and cosmic frontiers of particle physics target deeply connected questions. Dark matter, dark energy, cosmic inflation and baryogenesis have remained unexplained for decades, and the structure of the Standard Model itself provokes questions, not least in relation to the Higgs boson and neutrinos. Innovative and complementary experiments are needed across all areas of particle physics. Judging from the 2024 Aspen Winter Conference, the future of the field is in good hands.