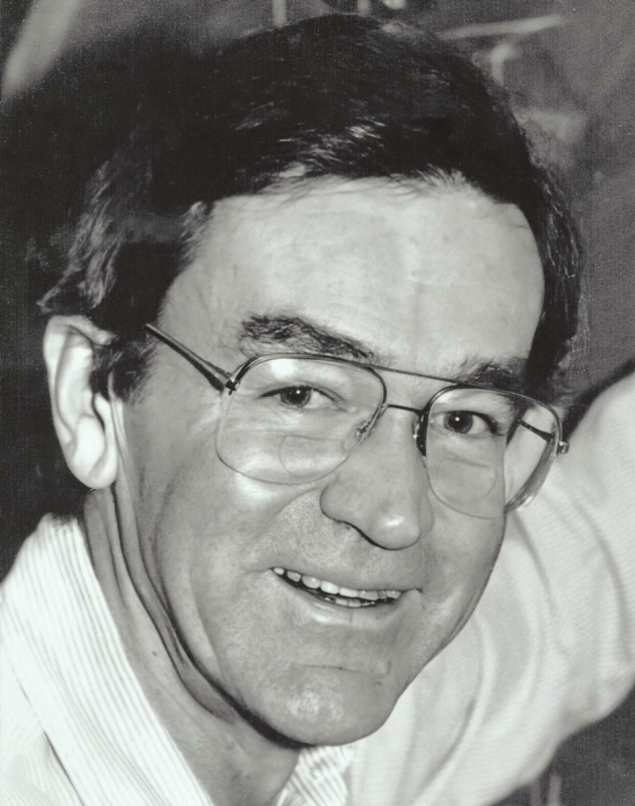

What motivates you to be CERN’s next Director-General?

CERN is an incredibly important organisation. I believe my deep passion for particle physics, coupled with the experience I have accumulated in recent years, including leading the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, DUNE, through a formative phase, and running the Science and Technology Facilities Council in the UK, has equipped me with the right skill set to lead CERN though a particularly important period.

How would you describe your management style?

That’s a good question. My overarching approach is built around delegating and trusting my team. This has two advantages. First, it builds an empowering culture, which in my experience provides the right environment for people to thrive. Second, it frees me up to focus on strategic planning and engagement with numerous key stakeholders. I like to focus on transparency and openness, to build trust both internally and externally.

How will you spend your familiarisation year before you take over in 2026?

First, by getting a deep understanding of CERN “from within”, to plan how I want to approach my mandate. Second, by lending my voice to the scientific discussion that will underpin the third update to the European strategy for particle physics. The European strategy process is a key opportunity for the particle-physics community to provide genuine bottom-up input and shape the future. This is going to be a really varied and exciting year.

What open question in fundamental physics would you most like to see answered in your lifetime?

I am going to have to pick two. I would really like to understand the nature of dark matter. There are a wide range of possibilities, and we are addressing this question from multiple angles; the search for dark matter is an area where the collider and non-collider experiments can both contribute enormously. The second question is the nature of the Higgs field. The Higgs boson is just so different from anything else we’ve ever seen. It’s not just unique – it’s unique and very strange. There are just so many deep questions, such as whether it is fundamental or composite. I am confident that we will make progress in the coming years. I believe the High-Luminosity LHC will be able to make meaningful measurements of the self-coupling at the heart of the Higgs potential. If you’d asked me five years ago whether this was possible, I would have been doubtful. But today I am very optimistic because of the rapid progress with advanced analysis techniques being developed by the brilliant scientists on the LHC experiments.

What areas of R&D are most in need of innovation to meet our science goals?

Artificial intelligence is changing how we look at data in all areas of science. Particle physics is the ideal testing ground for artificial intelligence, because our data is complex there are none of the issues around the sensitive nature of the data that exist in other fields. Complex multidimensional datasets are where you’ll benefit the most from artificial intelligence. I’m also excited by the emergence of new quantum technologies, which will open up fresh opportunities for our detector systems and also new ways of doing experiments in fundamental physics. We’ve only scratched the surface of what can be achieved with entangled quantum systems.

How about in accelerator R&D?

There are two areas that I would like to highlight: making our current technologies more sustainable, and the development of high-field magnets based on high-temperature superconductivity. This connects to the question of innovation more broadly. To quote one example among many, high-temperature superconducting magnets are likely to be an important component of fusion reactors just as much as particle accelerators, making this a very exciting area where CERN can deploy its engineering expertise and really push that programme forward. That’s not just a benefit for particle physics, but a benefit for wider society.

How has CERN changed since you were a fellow back in 1994?

The biggest change is that the collider experiments are larger and more complex, and the scientific and technical skills required have become more specialised. When I first came to CERN, I worked on the OPAL experiment at LEP – a collaboration of less than 400 people. Everybody knew everybody, and it was relatively easy to understand the science of the whole experiment.

My overarching approach is built around delegating and trusting my team

But I don’t think the scientific culture of CERN and the particle-physics community has changed much. When I visit CERN and meet with the younger scientists, I see the same levels of excitement and enthusiasm. People are driven by the wonderful mission of discovery. When planning the future, we need to ensure that early-career researchers can see a clear way forward with opportunities in all periods of their career. This is essential for the long-term health of particle physics. Today we have an amazing machine that’s running beautifully: the LHC. I also don’t think it is possible to overstate the excitement of the High-Luminosity LHC. So there’s a clear and exciting future out to the early 2040s for today’s early-career researchers. The question is what happens beyond that? This is one reason to ensure that there is not a large gap between the end of the High-Luminosity LHC and the start of whatever comes next.

Should the world be aligning on a single project?

Given the increasing scale of investment, we do have to focus as a global community, but that doesn’t necessarily mean a single project. We saw something similar about 10 years ago when the global neutrino community decided to focus its efforts on two complementary long-baseline projects, DUNE and Hyper-Kamiokande. From the perspective of today’s European strategy, the Future Circular Collider (FCC) is an extremely appealing project that would map out an exciting future for CERN for many decades. I think we’ll see this come through strongly in an open and science-driven European strategy process.

How do you see the scientific case for the FCC?

For me, there are two key points. First, gaining a deep understanding of the Higgs boson is the natural next step in our field. We have discovered something truly unique, and we should now explore its properties to gain deeper insights into fundamental physics. Scientifically, the FCC provides everything you want from a Higgs factory, both in terms of luminosity and the opportunity to support multiple experiments.

Second, investment in the FCC tunnel will provide a route to hadron–hadron collisions at the 100 TeV scale. I find it difficult to foresee a future where we will not want this capability.

These two aspects make the FCC a very attractive proposition.

How successful do you believe particle physics is in communicating science and societal impacts to the public and to policymakers?

I think we communicate science well. After all, we’ve got a great story. People get the idea that we work to understand the universe at its most basic level. It’s a simple and profound message.

Going beyond the science, the way we communicate the wider industrial and societal impact is probably equally important. Here we also have a good story. In our experiments we are always pushing beyond the limits of current technology, doing things that have not been done before. The technologies we develop to do this almost always find their way back into something that will have wider applications. Of course, when we start, we don’t know what the impact will be. That’s the strength and beauty of pushing the boundaries of technology for science.

Would the FCC give a strong return on investment to the member states?

Absolutely. Part of the return is the science, part is the investment in technology, and we should not underestimate the importance of the training opportunities for young people across Europe. CERN provides such an amazing and inspiring environment for young people. The scale of the FCC will provide a huge number of opportunities for young scientists and engineers.

We need to ensure that early-career researchers can see a clear way forward with opportunities in all periods of their career. This is essential for the long-term health of particle physics

In terms of technology development, the detectors for the electron–positron collider will provide an opportunity for pushing forward and deploying new, advanced technologies to deliver the precision required for the science programme. In parallel, the development of the magnet technologies for the future hadron collider will be really exciting, particularly the potential use of high-temperature superconductors, as I said before.

It is always difficult to predict the specific “return on investment” on the technologies for big scientific research infrastructure. Part of this challenge is that some of that benefits might be 20, 30, 40 years down the line. Nevertheless, every retrospective that has tried, has demonstrated that you get a huge downstream benefit.

Do we reward technical innovation well enough in high-energy physics?

There needs to be a bit of a culture shift within our community. Engineering and technology innovation are critical to the future of science and critical to the prosperity of Europe. We should be striving to reward individuals working in these areas.

Should the field make it more flexible for physicists and engineers to work in industry and return to the field having worked there?

This is an important question. I actually think things are changing. The fluidity between academia and industry is increasing in both directions. For example, an early-career researcher in particle physics with a background in deep artificial-intelligence techniques is valued incredibly highly by industry. It also works the other way around, and I experienced this myself in my career when one of my post-doctoral researchers joined from an industry background after a PhD in particle physics. The software skills they picked up from industry were incredibly impactful.

I don’t think there is much we need to do to directly increase flexibility – it’s more about culture change, to recognise that fluidity between industry and academia is important and beneficial. Career trajectories are evolving across many sectors. People move around much more than they did in the past.

Does CERN have a future as a global laboratory?

CERN already is a global laboratory. The amazing range of nationalities working here is both inspiring and a huge benefit to CERN.

How can we open up opportunities in low- and middle-income countries?

I am really passionate about the importance of diversity in all its forms and this includes national and regional inclusivity. It is an agenda that I pursued in my last two positions. At the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, I was really keen to engage the scientific community from Latin America, and I believe this has been mutually beneficial. At STFC, we used physics as a way to provide opportunities for people across Africa to gain high-tech skills. Going beyond the training, one of the challenges is to ensure that people use these skills in their home nations. Otherwise, you’re not really helping low- and middle-income countries to develop.

What message would you like to leave with readers?

That we have really only just started the LHC programme. With more than a factor of 10 increase in data to come, coupled with new data tools and upgraded detectors, the High-Luminosity LHC represents a major opportunity for a new discovery. Its nature could be a complete surprise. That’s the whole point of exploring the unknown: you don’t know what’s out there. This alone is incredibly exciting, and it is just a part of CERN’s amazing future.