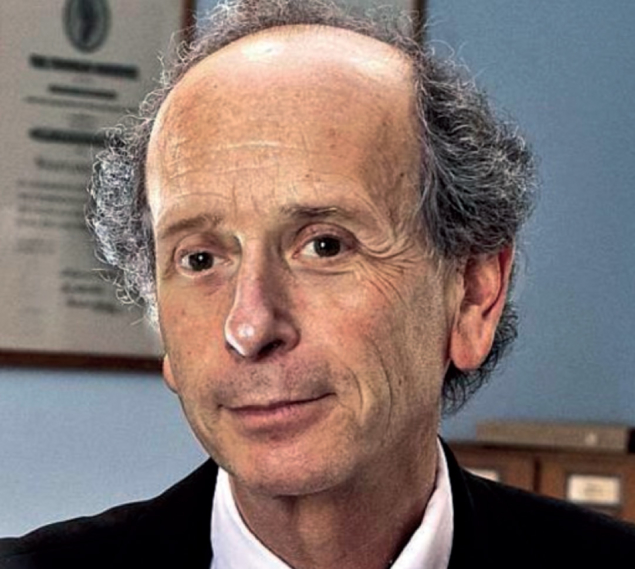

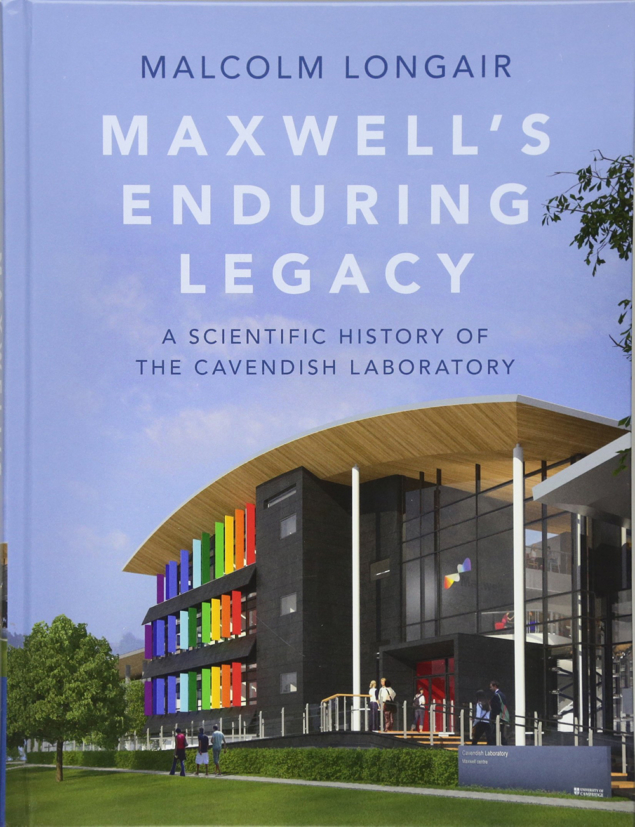

In 1871, James Clerk Maxwell undertook the titanic enterprise of planning a new physics laboratory for the University of Cambridge from scratch. To avoid mistakes, he visited the Clarendon Laboratory in Oxford, and the laboratory of William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) in Glasgow – then the best research institutes in the country – to learn all that he could from their experiences. Almost 150 years later, Malcolm Longair, a renowned astrophysicist and the Cavendish laboratory’s head from 1997 to 2005, has written a monumental account of the scientific achievements of those who researched, worked and taught at a laboratory which has become an indispensable part of the machinery of modern science.

The 22 chapters of the book are organised in ten parts corresponding to the inspiring figures who led the laboratory through the years, most famously among them Maxwell himself, Thomson, Rutherford, Bragg, Mott and few others. The numerous Nobel laureates who spent part of their careers at the Cavendish are also nicely characterised, among them Chadwick, Appleton, Kapitsa, Cockcroft and Walton, Blackett, Watson and Crick, Cormack, and, last but not least Didier Queloz, Nobel Laureate in 2019 and professor at the universities of Cambridge and Geneva. You may even read about friends and collaborators as the exposition includes the most recent achievements of the laboratory.

Rutherford and Thomson managed the finances of the laboratory almost from their personal cheque book

Besides the accuracy of the scientific descriptions and the sharpness of the ideas, this book inaugurates a useful compromise that might inspire future science historians. So far it was customary to write biographies (or collected works) of leading scientists and extensive histories of various laboratories: here these two complementary aspects are happily married in a way that may lead to further insights on the genesis of crucial discoveries. Longair elucidates the physics with a competent care that is often difficult to find. His exciting accounts will stimulate an avalanche of thoughts on the development of modern science. By returning to a time when Rutherford and Thomson managed the finances of the laboratory almost from their personal cheque book, this book will stimulate readers to reflect on the interplay between science, management and technology.

History is often instrumental in understanding where we come from, but it cannot reliably predict directions for the future. Nevertheless the history of the Cavendish shows that lasting progress can come from diversity of opinion, the inclusiveness of practices and mutual respect between fundamental sciences. How can we sum up the secret of the scientific successes described in this book? A tentative recipe might be unity in necessary things, freedom in doubtful ones and respect for every honest scientific endeavour.