With the boson confirmed, speculation inevitably grew about the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics. The prize is traditionally announced on the Tuesday of the first full week in October, at about midday in Stockholm. As it approaches, a highly selective epidemic breaks out: Nobelitis, a state of nervous tension among scientists who crave Nobel recognition. Some of the larger egos will have previously had their craving satisfied, only perhaps to come down with another fear: will I ever be counted as one with Einstein? Others have only a temporary remission, before suffering a renewed outbreak the following year.

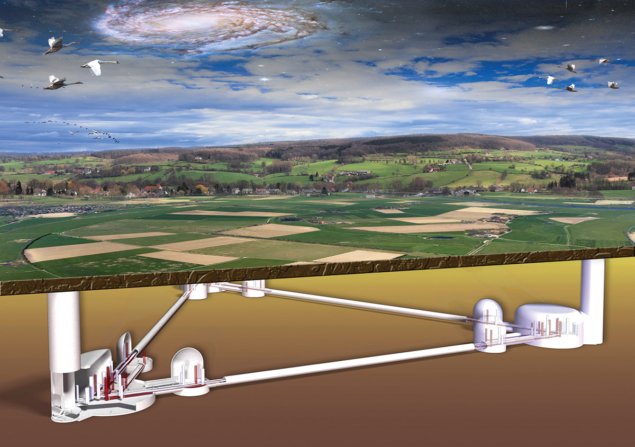

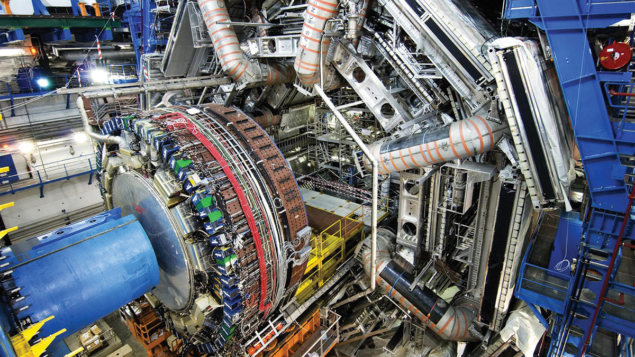

Three people at most can share a Nobel, and at least six had ideas like Higgs’s in the halcyon days of 1964 when this story began. Adding to the conundrum, the discovery of the boson involved teams of thousands of physicists from all around the world, drawn together in a huge cooperative venture at CERN, using a machine that is itself a triumph of engineering.

The 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics was announced on Tuesday 9 October and went to Serge Haroche and David Wineland for taking the first steps towards a quantum computer. Two days later, I went to Edinburgh to give a colloquium and met Higgs for a coffee beforehand. I asked him how he felt now that the moment had passed, at least for this year. “I’m enjoying the peace and quiet. My phone hasn’t rung for two days,” he remarked.

That the sensational discovery of 2012 was indeed of Higgs’s boson was, by the summer of 2013, beyond dispute. That Higgs was in line for a Nobel prize also seemed highly likely. Higgs himself, however, knew from experience that in the Stockholm stakes, nothing is guaranteed.

Back in 1982, at dawn on 5 October in the Midwest and the eastern US, preparations were in hand for champagne celebrations in three departments at two universities. At Cornell, the physics department hoped they would be honouring Kenneth Wilson, while over in the chemistry department their prospect was Michael Fisher. In Chicago, the physicists’ hero was to be Leo Kadanoff. Two years earlier the trio had shared the Wolf Prize, the scientific analogue of the Golden Globes to the Nobel’s Oscars, for their work on critical phenomena connected with phase transitions, fuelling speculation that a Nobel would soon follow. At the appointed hour in Stockholm, the chair of the awards committee announced that the award was to Wilson alone. The hurt was especially keen in the case of Michael Fisher, whose experience and teaching about phase transitions, illuminating the subtle changes in states of matter such as melting ice and the emergence of magnetism, had inspired Wilson, five years his junior. The omission of Kadanoff and Fisher was a sensation at the time and has remained one of the intrigues of Nobel lore.

Fisher’s agony was no secret to Peter Higgs. As undergraduates they had been like brothers and remained close friends for more than 60 years. Indeed, Fisher’s influence was not far away in July 1964, for it was while examining how some ideas from statistical mechanics could be applied to particle physics that Higgs had the insight that would become the capstone to the theory of particles and forces half a century later. For this he was to share the 2004 Wolf Prize with Robert Brout (who sadly died in 2011) and François Englert – just as Fisher, Kadanoff and Wilson had shared this prize in 1980. Then as October approached in 2013 Higgs became a hot favourite at least to share the Nobel Prize in Physics, and the bookmakers would only take bets at extreme odds-on.

Time to escape

In 2013, 8 October was the day when the Nobel decision would be announced. Higgs’s experiences the year before had helped him to prepare: “I decided not to be at home when the announcement was made with the press at my door; I was going to be somewhere else.” His first plan was to disappear into the Scottish Highlands by train, but he decided it was too complicated, and that he could hide equally well in Edinburgh. “All I would have to do is go down to Leith early enough. I knew the announcement would be around noon so I would leave home soon after 11, giving myself a safe margin, and have an early lunch in Leith about noon.”

Richard Kenway, the Tait Professor of Mathematical Physics at Edinburgh and one of the university’s vice principals, confirmed the tale. “That was what we were all told, and he completely convinced us. Right up to the actual moment when we were sitting waiting for the [Nobel] announcement, we thought he had disappeared off somewhere into the Highlands.” Some newspapers got the fake news from the department, and one reporter even went up into the Highlands to look for him.

As scientists and journalists across the world were glued to the live broadcast, the Nobel committee was still struggling to reach the famously reclusive physicist. The announcement of his long-awaited crown was delayed by about half an hour until they decided they could wait no longer. Meanwhile, Peter Higgs sat at his favourite table in The Vintage, a seafood bar in Henderson Street, Leith, drinking a pint of real ale and considering the menu. As the committee announced that it had given the prize to François Englert and Peter Higgs “for the theoretical discovery of a mechanism that contributes to our understanding of the origin of mass of subatomic particles, and which recently was confirmed through the discovery of the predicted fundamental particle, by the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider”, phones started going off in the Edinburgh physics department.

Higgs finished his lunch. It seemed a little early to head home, so he decided to look in at an art exhibition. At about three o’clock he was walking along Heriot Row in Edinburgh, heading for his flat nearby, when a car pulled up near the Queen Street Gardens. “A lady in her 60s, the widow of a high-court judge, got out and came across the road in a very excited state to say, ‘My daughter phoned from London to tell me about the award’, and I said, ‘What award?’ I was joking of course, but that’s when she confirmed that I had won the prize. I continued home and managed to get in my front door with no more damage than one photographer lying in wait.” It was only later that afternoon that he finally learned from the radio news that the award was to himself and Englert.

Suited and booted

On arrival in Stockholm in December 2013, after a stressful two-day transit in London, Higgs learned that one of the first appointments was to visit the official tailor. The costume was to be formal morning dress in the mid-19th-century style of Alfred Nobel’s time, including elegant shoes adorned with buckles. As Higgs recalled, “Getting into the shirt alone takes considerable skill. It was almost a problem in topology.” The demonstration at the tailor’s was hopeless. Higgs was tense and couldn’t remember the instructions. On the day of the ceremony, fortunately, “I managed somehow.” Then there were the shoes. The first pair were too small, but when he tried bigger ones, they wouldn’t fit comfortably either. He explained, “The problem is that the 19th-century dress shoes do not fit the shape of one’s foot; they were rather pointy.” On the day of the ceremony both physics laureates had a crisis with their shoes. “Englert called my room: ‘I can’t wear these shoes. Can we agree to wear our own?’ So we did. We were due to be the first on the stage and it must have been obvious to everyone in the front row that we were not wearing the formal shoes.”

Robert Brout in spirit completed a trinity of winners

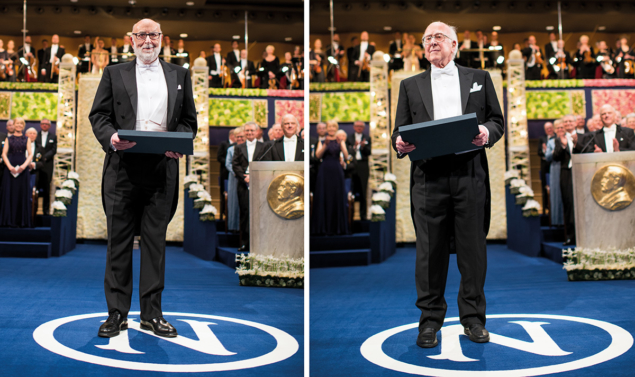

On the afternoon of 10 December, nearly 2000 guests filled the Stockholm Concert Hall to see 12 laureates receive their awards from King Gustav of Sweden. They had been guided through the choreography of the occasion earlier, but on the day itself, performing before the throng in the hall, there would be first-night nerves for this once-in-a-lifetime theatre. Winners of the physics prize would be called to receive their awards first, while the others watched and could see what to expect when they were named. The scenery, props and supporting cast were already in place. These included former winners dressed in tail suits and proudly wearing the gold button stud that signifies their membership of this unique club. Among them were Carlo Rubbia, discoverer of the W and Z particles, who instigated the experimental quest for the boson and won the prize in 1984; Gerard ’t Hooft, who built on Higgs’s work to complete the theoretical description of the weak nuclear force and won in 1999; and 2004 winner Frank Wilczek, who had built on his own prize-winning work to identify the two main pathways by which the Higgs boson had been discovered.

After a 10-minute oration by the chair of the Nobel Foundation and a musical interlude, Lars Brink, chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics, managed to achieve one of the most daunting challenges in science pedagogy, successfully addressing both the general public in the hall and the assembled academics, including laureates from other areas of science. The significance of what we were celebrating was beyond doubt: “With discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, the Standard Model of physics was complete. It has been proved that nature follows precisely that law that Brout, Englert and Higgs created. This is a fantastic triumph for science,” Brink announced. He also introduced a third name, that of Englert’s collaborator, Robert Brout. In so doing, he made an explicit acknowledgement that Brout in spirit completed a trinity of winners.

Brink continued with his summary history of how their work and that of others established the Standard Model of particle physics. Seventeen months earlier the experiments at the LHC had confirmed that the boson is real. What had been suspected for decades was now confirmed forever. The final piece in the Standard Model of particle physics had been found. The edifice was robust. Why this particular edifice is the one that forms our material universe is a question for the future. Brink now made the formal invitation for first Englert and then Higgs to step forward to receive their share of the award.

Higgs, resplendent in his formal suit, and comfortable in his own shoes, rose from his seat and prepared to walk to centre-stage. Forty-eight years since he set out on what would be akin to an ascent of Everest, Higgs had effectively conquered the Hillary step – the final challenge before reaching the peak – on 4 July 2012 when the existence of his boson was confirmed. Now, all that remained while he took nine steps to reach the summit was to remember the choreography: stop at the Nobel Foundation insignia on the carpet; shake the king’s hand with your right hand while accepting the Nobel prize and diploma with the other. Then bow three times, first to the king, then to the bust of Alfred Nobel at the rear of the stage, and finally to the audience in the hall.

Higgs successfully completed the choreography and accepted his award. As a fanfare of trumpets sounded, the audience burst into applause. Higgs returned to his seat. The chairman of the chemistry committee took the lectern to introduce the winners of the chemistry prize. To his relief, Higgs was no longer in the spotlight.

All in a name

The saga of Higgs’s boson had begun with a classic image – a lone genius unlocking the secrets of nature through the power of human thought. The fundamental nature of Higgs’s breakthrough had been immediately clear to him. However, no one, least of all Higgs, could have anticipated that it would take nearly half a century and several false starts to get from his idea to a machine capable of finding the particle. Nor did anyone envision that this single “good idea” would turn a shy and private man into a reluctant celebrity, accosted by strangers in the supermarket. Some even suggested that the reason why the public became so enamoured with Higgs was the solid ordinariness of his name, one syllable long, unpretentious, a symbol of worthy Anglo-Saxon labour.

In 2021, nine years after the discovery, we were reminiscing about the occasion when, to my surprise, Higgs suddenly remarked that it had “ruined my life”. To know nature through mathematics, to see your theory confirmed, to win the plaudits of your peers and join the exclusive club of Nobel laureates: how could all this equate with ruin? To be sure I had not misunderstood, I asked again the next time we spoke. He explained: “My relatively peaceful existence was ending. I don’t enjoy this sort of publicity. My style is to work in isolation, and occasionally have a bright idea.”

- This is an edited extract from Elusive: How Peter Higgs Solved the Mystery of Mass, by Frank Close, published on 14 June (Basic Books, US) and 7 July (Allen Lane, UK)