Last year marked the 10th anniversary of the discovery of the Higgs particle. Ten years is a short lapse of time when we consider the profound implications of this discovery. Breakthroughs in science mark a leap in understanding, and their ripples may extend for decades and even centuries. Take Kirchhoffs’ blackbody proposal more than 150 years ago: a theoretical construction, an academic exercise that opened the path towards a quantum revolution, the implications of which we are still trying to understand today.

Imagine now the vast network of paths opened by ideas, such as emission theory, that led to no fruition despite their originality. Was pursuing these useful, or a waste of resources? Scientists would answer that the spirit of basic research is precisely to follow those paths with unknown destinations; it’s how humanity reached the level of knowledge that sustains modern life. As particle physicists, as long as the aim is to answer nature’s outstanding mysteries, the path is worth following. The Higgs-boson discovery is the latest triumph of this approach and, as for the quantum revolution, we are still working hard to make sense of it.

Particle discoveries are milestones in the history of our field, but they signify something more profound: the realisation of a new principle in nature. Naively, it may seem that the Higgs discovery marked the end of our quest to understand the TeV scale. The opposite is true. The behaviour of the Higgs boson, in the form it was initially proposed, does not make sense at a quantum level. As a fundamental scalar, it experiences quantum effects that grow with their energy, doggedly pushing its mass towards the Planck scale. The Higgs discovery solidified the idea that gauge symmetries could be hidden, spontaneously broken by the vacuum. But it did not provide an explanation of how this mechanism makes sense with a fundamental scalar sensitive to mysterious phenomena such as quantum gravity.

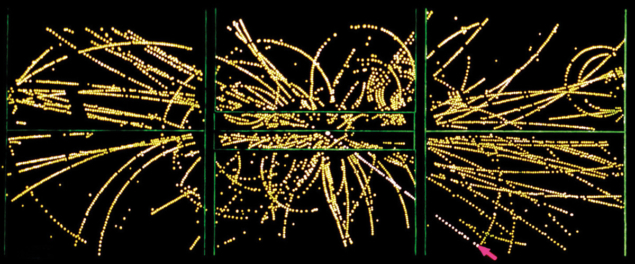

Now comes the hard part. From the plethora of ideas proposed during the past decades to make sense of the Higgs boson – supersymmetry being the most prominent – most physicists predicted that it would have an entourage of companion particles with electroweak or even strong couplings. Arguments of naturalness, that these companions should be close-by to prevent troublesome fine-tunings of nature, led to the expectation that discoveries would follow or even precede that of the Higgs. Ten years on, this wish has not been fulfilled. Instead, we are faced with a cold reality that can lead us to sway between attitudes of nihilism and hubris, especially when it comes to the question of whether particle physics has a future beyond the Higgs. Although these extremes do not apply to everyone, they are understandable reactions to viewing our field next to those with more immediate applications, or to the personal disappointment of a lifelong career devoted to ideas that were not chosen by nature.

Such despondence is not useful. Remember that the no-lose theorem we enjoyed when planning the LHC, i.e. the certainty that we would find something new, Higgs boson or not, at the TeV scale, was an exception to the rules of basic research. Currently, there is no no-lose theorem for the LHC, or for any future collider. But this is precisely the inherent premise of any exploration worth doing. After the incredible success we have had, we need to refocus and unify our discourse. We face the uncertainty of searching in the dark, with the hope that we will initiate the path to a breakthrough, still aware of the small likelihood that this actually happens.

The no-lose theorem we enjoyed when planning the LHC was an exception to the rules of basic research

Those hopes are shared by wider society, which understands the importance of exploring big questions. From searching for exoplanets that may support life to understanding the human mind, few people assume these paths will lead to immediate results. The challenge for our field is to work out a coherent message that can enthuse people. Without straying far from collider physics, we could notice that there is a different type of conversation going on in the search for dark matter. Here, there is no no-lose theorem either, and despite the current exclusion of most vanilla scenarios, there is excitement and cohesion, which are effectively communicated. As for our critics, they should be openly confronted and viewed as an opportunity to build stronger arguments.

We have powerful arguments to keep delving into the smallest scales, with the unknown nature of dark matter, neutrinos and the matter–antimatter asymmetry the most well-known examples. As a field, we need to renew the excitement that led us where we are, from the shock of watching alpha particles bounce back from a thin gold sheet, to building a colossus like the LHC. We should be outspoken about our ambition to know the true face of nature and the profound ideas we explore, and embrace the new path that the Higgs discovery has opened.