The standard criterion for claiming a discovery in particle physics is that the observed effect should have the equivalent of a five standard-deviation (5σ) discrepancy with already known physics, i.e. the Standard Model (SM). This means that the chance of observing such an effect or larger should be at most 3 × 10–7, assuming it is merely a statistical fluctuation, which corresponds to the probability of correctly guessing whether a coin will fall down heads or tails for each of 22 tosses. Statisticians claim that it is crazy to believe probability distributions so far into their tails, especially when systematic uncertainties are involved; particle physicists still hope that they provide some measure of the level of (dis)agreement between data and theory. But what is the origin of this convention, and does it remain a relevant marker for claiming the discovery of new physics?

There are several reasons why the stringent 5σ rule is used in particle physics. The first is that it provides some degree of protection against falsely claiming the observation of a discrepancy with the SM. There have been numerous 3σ and 4σ effects in the past that have gone away when more data was collected. A relatively recent example was an excess of diphoton events at an energy of 750 GeV seen in both the ATLAS and CMS data of 2015, but which was absent in the larger data samples of 2016.

Systematic errors provide another reason, since such effects are more difficult to assess than statistical uncertainties and may be underestimated. Thus in a systematics-dominated scenario, if our estimate is a factor of two too small, a more mundane 3σ fluctuation could incorrectly be inflated to an apparently exciting 6σ effect. A potentially more serious problem is a source of systematics that has not even been considered by the analysts, the so-called “unknown unknowns”.

Know your p-values

Another reason underlying the 5σ criterion is the look-elsewhere effect, which involves the “p-values” for the observed effect. These are defined as the probability of a statistical fluctuation causing a result to be as extreme as the one observed, or more so, assuming some null hypothesis. For example, in tossing an unbiased coin 10 times, and observing eight of them to be tails when we bet on each of them being heads, it is the probability of being wrong eight or nine or 10 times (5.5%). A small p-value indicates a tension between the theory and the observation.

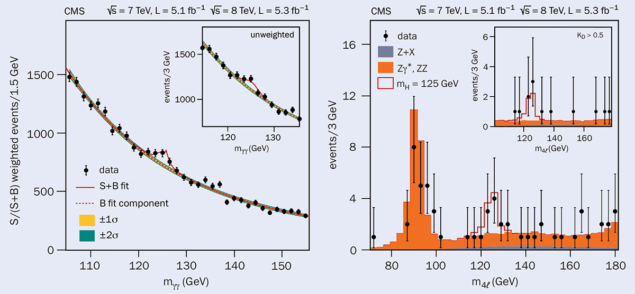

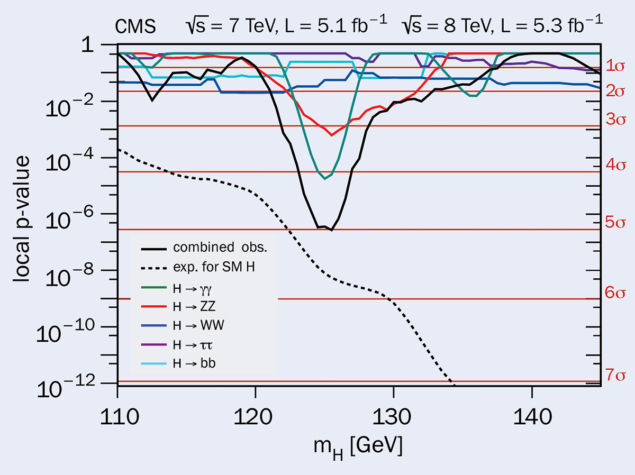

Particle-physics analyses often look for peaks in mass spectra, which could be the sign of a new particle. An example is shown in the “Higgs signals” figure, which contains data from CMS used to discover the Higgs boson (ATLAS has similar data). Whereas the local p-value of an observed effect is the chance of a statistical fluctuation being at least as large as the observed one at its specific location, more relevant is a global p-value corresponding to a fluctuation anywhere in the analysis, which has a higher probability and hence reduces the significance. The local p-values corresponding to the data in “Higgs signals” are shown in the figure “p-values”.

A non-physics example highlighting the difference between local and global p-values was provided by an archaeologist who noticed that a direction defined by two of the large stones at the Stonehenge monument pointed at a specific ancient monument in France. He calculated that the probability of this was very small, assuming that the placement of the stones was random (local p-value), and hence that this favoured the hypothesis that Stonehenge was designed to point in that way. However, the chance that one of the directions, defined by any pair of stones, was pointing at an ancient monument anywhere in the world (global p-value) is above 50%.

Current practice for model-dependent searches in particle physics, however, is to apply the 5σ criterion to the local p-value, as was done in the search for the Higgs boson. One reason for this is that there is no unique definition of “elsewhere”; if you are a graduate student, it may be just your own analysis, while for CERN’s Director-General, “anywhere in any analysis carried out with data from CERN” may be more appropriate. Another is that model-independent searches involving machine-learning techniques are capable of being sensitive to a wide variety of possible new effects, and it is hard to estimate what their look-elsewhere factor should be. Clearly, in quoting global p-values it is essential to specify your interpretation of elsewhere.

A fourth factor behind the 5σ rule is plausibility. The likelihood of an observation is the probability of the data, given the model. To convert this to the more interesting probability of the model, given the data, requires the Bayesian prior probability of the model. This is an example of the probability of an event A, assuming that B is true, not in general being the same as the probability of B, given A. Thus the probability of a murderer eating toast for breakfast may be 60%, but the probability of someone who eats toast for breakfast being a murderer is thankfully much smaller (about one in a million). In general, our belief in the plausibility in a model for a particular version of new physics is much smaller than for the SM, thus being an example of the old adage that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”. Since these factors vary from one analysis to another, one can argue that it is unreasonable to use the same discovery criterion everywhere.

There are other relevant aspects of the discovery procedure. Searches for new physics can be just tests for consistency with the SM; or they can see which of two competing hypotheses (“just SM” or “SM plus new physics”) provides a better fit to the data. The former are known as goodness-of-fit tests and may involve χ2, Kolmogorov–Smirnov or similar tests; the latter are hypothesis tests, often using the likelihood ratio. They are sometimes referred to as model-independent and model-dependent, respectively, each having its own advantages and limitations. However, the degree of model dependence is a continuous spectrum rather than a binary choice.

It is unreasonable to regard 5.1σ as a discovery, but 4.9σ as not. Also, should we regard the one with better observed accuracy or better expected accuracy as the preferred result? Blind analyses are recommended, in that this removes the possibility of the analyser adjusting selections to influence the significance of the observed effect. Some non-blind searches have such a large and indeterminate look-elsewhere effect that they can only be regarded as hints of new physics, to be confirmed by future independent data. Theory calculations also have uncertainties, due for example to parameters in the model or difficulties with numerical predictions.

Discoveries in progress

A useful exercise is to review a few examples that might be (or might have been) discoveries. A recent example involves the ATLAS and CMS observation of events involving four-top quarks. Apart from the similarity of the heroic work of the physicists involved, these analyses have interesting contrasts with the Higgs-boson discovery. First, the Higgs discovery involved clear mass peaks, while the four-top events simply caused an enhancement of events in the relevant region of phase space (see “Four tops” figure). Then, the four-top production is just a verification of an SM prediction and indeed it would have been more of a surprise if the measured rate had been zero. So this is just an observation of an expected process, rather than a new discovery. Indeed, both preprints use the word “observation” rather than “discovery”. Finally, although 5σ was the required criterion for discovering the Higgs boson, surely a lower level of significance would have been sufficient for the observation of four-top events.

the figure) and from the four-top signal (red). The GNN was trained to distinguish between the signal and backgrounds. The agreement between data and prediction is clearly much improved by the inclusion of the four-top signal. Source: arXiv.org:2303.15061

Going back further in time, an experiment in 1979 claimed to observe free quarks by measuring the electrical charge of small spheres levitated in an oscillating electric field; several gave multiples of 1/3, which was regarded as a signature of single quarks. Luis Alvarez noted that the raw results required sizeable corrections and suggested that a blind analysis should be performed on future data. The net result was that no further papers were published on this work. This demonstrates the value of blind analyses.

A second historical example is precision measurements at the Large Electron Positron collider (LEP). Compared with the predictions of the SM, including the then-known particles, deviations were observed in the many measurements made by the four LEP experiments. A much better fit to the data was achieved by including corrections from the (at that time hypothesised) top quark and Higgs boson, which enabled approximate mass ranges to be derived for them. However, it is now accepted that the discoveries of the top quark and the Higgs boson were subsequently made by their direct observations at the Tevatron and at the LHC, rather than by their virtual effects at LEP.

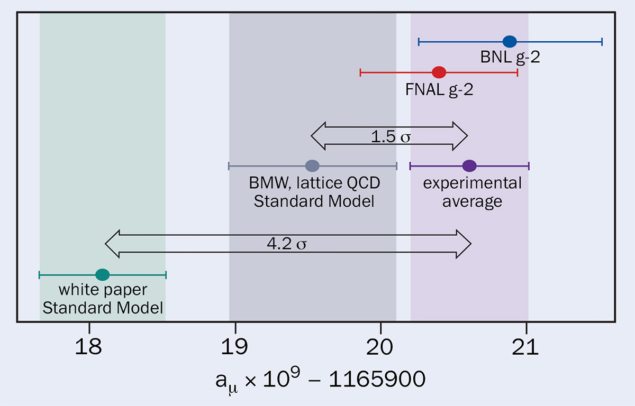

The muon magnetic moment is a more contemporary case. This quantity has been measured and also predicted to incredible precision, but a discrepancy between the two values exists at around the 4σ level, which could be an indication of contributions from virtual new particles. The experiment essentially measures just this one quantity, so there is no look-elsewhere effect. However, even if this discrepancy persists in new data, it will be difficult to tell if it is due to the theory or experiment being wrong, or whether it requires the existence of new, virtual particles. Also, the nature of such virtual particles could remain obscure. Furthermore, a recent calculation using lattice gauge theory of the “vacuum hadronic polarisation” contribution to the predicted value of the magnetic moment brings it closer to the observed value (see “Measurement of the moment” figure). Clearly it will be worth watching how this develops.

Our hope for the future is that the current 5σ criterion will be replaced by a more nuanced approach for what qualifies as a discovery

The so-called flavour anomalies are another topical example. The LHCb experiment has observed several anomalous results in the decays of B mesons, especially those involving transitions of a b quark to an s quark and a lepton pair. It is not yet clear whether these could be evidence for some real discrepancies with the SM prediction (i.e. evidence for new physics), or simply and more mundanely an underestimate of the systematics. The magnitude of the look-elsewhere effect is hard to estimate, so independent confirmation of the observed effects would be helpful. Indeed, the most recent result from LHCb for the R(K) parameter, published in December 2022, is much more consistent with the SM. It appears that the original result was affected by an overlooked background source. Repeated measurements by other experiments are eagerly awaited.

A surprise last year was the new result by the CDF collaboration at the former Tevatron collider at Fermilab, which finished collecting data many years ago, on the mass of the W boson (mW), which disagreed with the SM prediction by 7σ. It is of course more reasonable to use the weighted average of all mW measurements, which reduces the discrepancy, but only slightly. A subsequent measurement by ATLAS disagreed with the CDF result; the CMS determination of mW is awaited with interest.

Nuanced approach

It is worth noting that the muon g-2, flavour and mW discrepancies concern tests of the SM predictions, rather than direct observation of a new particle or its interactions. Independent confirmations of the observations and the theoretical calculations would be desirable.

One of the big hopes for further running of the LHC is that it will result in the “discovery” of Higgs pair production. But surely there is no reason to require a 5σ discrepancy with the SM in order to make such claim? After all, the Higgs boson is known to exist, its mass is known and there is no big surprise in observing its pair-production rate being consistent with the SM prediction. “Confirmation” would be a better word than “discovery” for this process. In fact, it would be a real discovery if the di-Higgs production rate was found to be significantly above or below the SM prediction. A similar argument could be applied to the searches for single top-quark production at hadron colliders, and decays such as H → μμ or Bs → μμ. This should not be taken to imply that LHC running can be stopped once a suitable lower level of significance is reached. Clearly there will be interest in using more data to study di-Higgs production in greater detail.

Our hope for the future is that the current 5σ criterion will be replaced by a more nuanced approach for what qualifies as a discovery. This would include just quoting the observed and expected p-values; whether the analysis is dominated by systematic uncertainties or statistical ones; the look-elsewhere effect; whether the analysis is robust; the degree of surprise; etc. This may mean leaving it for future measurements to determine who deserves the credit for a discovery. It may need a group of respected physicists (e.g. the directors of large labs) to make decisions as to whether a given result merits being considered a discovery or needs further verification. Hopefully we will have several of these interesting decisions to make in the not-too-distant future.