Every two years since 1987 the ICFA Instrumentation Panel, as an activity of the International Committee for Future Accelerators, has organized an international school of instrumentation. The main aim of the school is to promote interest in nuclear instrumentation among graduate students and young researchers from developing countries. ICFA2001, which was held from 25 March to 8 April, was hosted by the National Accelerator Centre in Faure, near Cape Town, South Africa. It was the first such school to be held on the African continent.

ICFA2001 was devoted to the physics and technologies of instrumentation in elementary particle physics, with a slant towards devices and applications that generate and process image-like information from radiation detectors on a quantum-by-quantum basis. The basic research and spin-offs from the application of such instrumentation to high-energy physics, medicine, microbiology and nuclear sciences, as well as research and development for non-destructive testing in industry, attest to the importance of this vital and continuously growing field.

Instrumentation is usually developed in university laboratories with relatively low investment costs, but access to the latest technology is possible by means of co-operative ventures with other institutes, and in particular with large international research centres and industry. Access to instrumentation technology is a key tenet for the ICFA Instrumentation Panel. At ICFA2001, the organizers, speakers and instructors joined with Kobus Lawrie, Naomi Haasbroek and the rest of the National Accelerator Centre staff in an effort not only to provide access to instrumentation technology and stimulate development in experimental particle physics instrumentation, but also to reinforce the “Science for Africa” motto of South Africa’s National Accelerator Centre.

As far as content and structure were concerned, the main feature of this school – unique to high-energy physics – was its direct, hands-on approach. Students attended morning lectures, after which there were afternoon laboratory sessions lasting four to six hours. Lecture topics this year were wide-ranging, including introductory courses on the physics of particle detection, gaseous detectors, particle identification, calorimetry, silicon detectors, signal processing and data acquisition, as well as several review talks devoted to new technologies, applications in medical physics, molecular biology, astrophysics and data acquisition.

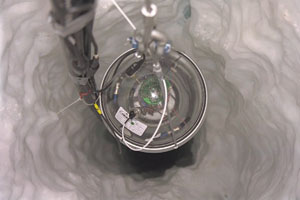

The laboratory classes were state-of-the-art instrumentation sessions, led by researchers in the fields in question from universities and research labs all over the world. In some cases they had simply packed up their current research project and shipped it to South Africa, so that students could get a true taste of what is currently of interest.

Students worked in small groups to carry out selected experimental techniques, using multiwire proportional chambers; drift chambers; silicon detectors; microstrip gas chambers; analogue and digital circuits; and data acquisition. They also worked with specific applications in medical imaging, cosmic rays and protein crystallography.

Satisfied students

A measure of its success is that the anonymous student evaluations that were collected at the end of the school overwhelmingly reflected the enthusiasm and satisfaction of the students. As was the case in previous schools, the students placed a strong emphasis on the importance of the laboratory sessions. The labs provided many students with their first hands-on experience of nuclear instrumentation, and offered those students who were well versed in issues of instrumentation a varied and challenging “playground”.

The school also provided a stimulating human experience for its students, some of whom had never attended a scientific meeting abroad, and for whom it was their first excursion outside their home country.

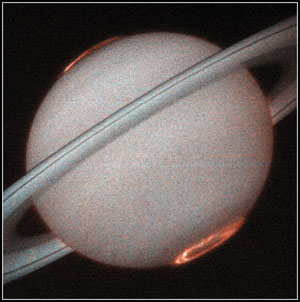

Those involved in running the school also found it rewarding, owing to the energy and enthusiasm that was generated by all who took part. One student even asked if she could skip lunch in order to return to the lab to finish a measurement from the day before. In another instance, Michel Spiro was bombarded with more than 20 questions during his evening public lecture on astrophysics and cosmology. A number of lecturers and instructors are continuing the discussions that they began with students at the school, with a view to potential scientific collaboration.

The decision to hold the school in Africa was made in an attempt to make an impact on young African researchers and postgraduate students who were interested in nuclear instrumentation. Previous workshops had attracted, on average, only one or two African students.

ICFA2001 achieved this goal and was a resounding success. Of the 96 students in the school, 45 were African, and they represented 12 different countries. Not only was the students’ level of preparation high, but all brought with them a remarkable enthusiasm for the subject. Many had a clear understanding of the instrumentation needs faced by their home countries, which were, in general, related to applications such as nuclear medicine and ambient protection (as in the case of a student from Sierra Leone who was working on radioactive waste management). Yet it was clear that such pragmatism is balanced by a common sentiment that involvement in basic research might be a way to slow down the “brain drain” from their home countries.

Follow-up programme

To promote “Science for Africa” further, ICFA has launched a new programme this year that provides a follow-up to the school, by means of a number of summer student placements offered by CERN and DESY (and Fermilab is expected to participate next year). Suitable candidates were easily identified among the students of the school, and all studentships have been accepted.

It was also clear that South Africa might be able to act as a catalyst for science, and, in particular, nuclear physics, at a regional level, providing higher education to students from countries such as Kenya, Zambia and Mozambique. African students who distinguished themselves came not only from South Africa (primarily from the National Accelerator Centre) but also from Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania.

With “Science for Africa” as its motto, the National Accelerator Centre has made its objectives clear. Indeed, the centre’s leading role in African science was apparent throughout the school, as was the significant support given by local scientific authorities.

Small but active

The facilities at the National Accelerator Centre are good, despite the cashflow crisis in the past couple of years that has triggered a downsizing of its workforce. The centre has overcome that hurdle and has a stable workforce of about 200 staff. Its experimental physics group is small but active and includes several young postgraduates who are working on MScs and PhDs. Significant effort is being made to bridge the age gap and remedy racial disparity.

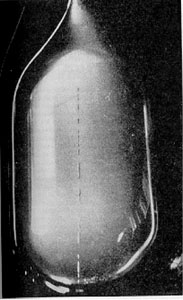

With these resources the centre carries out several programmes. Its radiation therapy programme includes impressive facilities for neutron and proton therapy with which hundreds of patients have been treated, while its production of isotopes for medical applications brings in additional income for the centre through their sale on both the national and the international markets. The centre also runs a nuclear physics programme, including the use of a spectrometer to study nuclear reactions, and a new state-of-the-art “gamma ball” (Afrodite), which has attracted foreign experimentalists from such laboratories as INFN-Milano, Italy; and another on material science, using a nuclear microprobe on a 6 MV Van de Graaff accelerator.

Activities are based on a large separated sector cyclotron that accelerates protons to energies of 200 MeV, and heavier particles to much higher energies. Two smaller cyclotrons are also used to provide intense beams of light ions, polarized light ions or heavy ions for injection into the large cyclotron. The beam time from the cyclotron is shared equally among the three main programmes, with some beam allocated specifically to the experimental physics community at weekends, when users come in from several South African universities and from abroad.

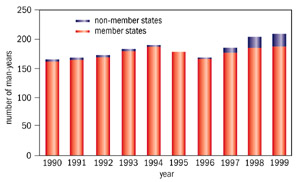

ICFA2001 was the eighth edition of the school. Previous editions took place at ICTP Trieste, Italy, in 1987, 1989 and 1991; in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1990; in Bombay, India, in 1993; in Ljubljana, Slovenia, in 1995; in Léon, Guanajuato, Mexico, in 1997; and in Istanbul, Turkey, in 1999.

The ICFA2001 instrumentation school was jointly supported by the National Research Foundation, DACST, ESCAM and NESCA of South Africa, and by CERN, DESY, INFN, ICTP, IN2P3, RAL, DOE and NSF.