The Forward Physics Facility (FPF) is a proposed new facility to operate concurrently with the High-Luminosity LHC, housing several new experiments on the ATLAS collision axis. The FPF offers a broad, far-reaching physics programme ranging from neutrino, QCD and hadron-structure studies to beyond-the-Standard Model (BSM) searches. The project, which is being studied within the Physics Beyond Colliders initiative, would exploit the pre-existing HL-LHC beams and thus have minimal energy-consumption requirements.

On 8 and 9 June, the 6th workshop on the Forward Physics Facility was held at CERN and online. Attracting about 160 participants, the workshop was organised in sessions focusing on the facility design, the proposed experiments and physics studies, leaving plenty of time for discussion about the next steps.

Groundbreaking

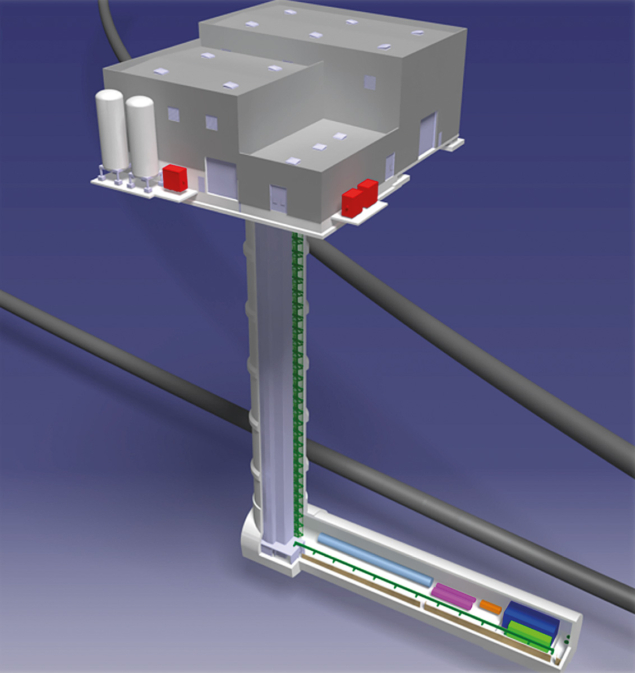

Regarding the facility itself, CERN civil-engineering experts presented its overall design: a 65 m-long, 10 m-high/wide cavern connected to the surface via an 88 m-deep shaft. The facility is located 600 m from the ATLAS collision point, in the SM18 area of CERN. A workshop highlight was the first results from a site investigation study, whereby a 20 cm-diameter core was taken at the proposed location of the FPF shaft to a depth of 100 m. The initial analysis of the core showed that the geological conditions are positive for work in this area. Other encouraging studies towards confirming the FPF feasibility were FLUKA simulations of the expected muon flux in the cavern (the main background for the experiments), the expected radiation level (shown to allow people to enter the cavern during LHC operations with various restrictions), and the possible effect on beam operations of the excavation works. One area where more work is required concerns the possible need to install a sweeper magnet in the LHC tunnel between ATLAS and the FPF to reduce the muon backgrounds.

Currently there are five proposed experiments to be installed in the FPF: FASER2 (to search for decaying long-lived particles); FASERν2 and AdvSND (dedicated neutrino detectors covering complementary rapidity regions); FLArE (a liquid-argon time projection chamber for neutrino physics and light dark-matter searches); and FORMOSA (a scintillator-based detector to search for milli-charged particles). The three neutrino detectors offer complementary designs to exploit the huge number of TeV energy neutrinos of all flavours that would be produced in such a forward-physics configuration. Four of these have smaller pathfinder detectors, FASER(ν), SND@LHC and milliQan that are already operating during LHC Run 3. First results from these pathfinder experiments were presented at the CERN workshop, including the first ever direct observation of collider neutrinos by FASER and SND@LHC, which provide a key proof of principle for the FPF. The latest conceptual design and expected performance of the FPF experiments were presented. Furthermore, first ideas on models to fund these experiments are in place and were discussed at the workshop.

In the past year, much progress has been made in quantifying the physics case of the FPF. It effectively extends the LHC with a “neutrino–ion collider’’ with complementary reach to the Electron–Ion Collider under construction in the US. The large number of high-energy neutrino interactions that will be observed at the FPF allows detailed studies of deep inelastic scattering to constrain proton and nuclear parton distribution functions (PDFs). Dedicated projections of the FPF reveal that uncertainties in light-quark PDFs could be reduced by up to a factor of two or even more compared to current models, leading to improved HL-LHC predictions for key measurements such as the W-boson mass.

In the past year, much progress has been made in quantifying the physics case of the FPF

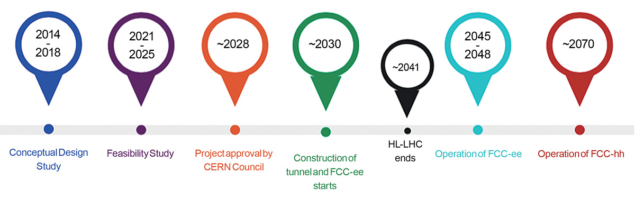

High-energy electrons and tau neutrinos at the FPF predominantly arise from forward charm production. This is initiated by gluon–gluon scattering involving very low and high momentum fractions, with the former reaching down to Bjorken-x values of 10–7 – beyond the range of any other experiment. The same FPF measurements of forward charm production are relevant for testing different models of QCD at small-x, which would be instrumental for Higgs production at the proposed Future Circular Collider (FCC-hh). This improved modeling of forward charm production is also essential for understanding the backgrounds to diffuse astrophysics neutrinos at telescopes such as IceCube and KM3NeT. In addition, measurements of the ratio of electron-to-muon neutrinos at the FPF probe forward kaon-to-pion production ratios that could explain the so-called muon puzzle (a deficit in muons in simulations compared to measurements), affecting cosmic-ray experiments.

The FPF experiments would also be able to probe a host of BSM scenarios in uncharted regions of parameter space, such as dark-matter portals, dark Higgs bosons and heavy neutral leptons. Furthermore, experiments at the FPF will be sensitive to the scattering of light dark-matter particles produced in LHC collisions, and the large centre-of-mass energy enables probes of models, such as quirks (long-lived particles that are charged under a hidden-sector gauge interaction), and some inelastic dark-matter candidates, which are inaccessible at fixed-target experiments. On top of that, the FPF experiments will significantly improve the sensitivity of the LHC to probe millicharged particles.

The June workshop confirmed both the unique physics motivation for the FPF and the excellent progress in technical and feasibility studies towards realising it. Motivated by these exciting prospects, the FPF community is now working on a Letter of Intent to submit to the LHC experiments committee as the next step.