The tide of the Second World War turned in the Allies’ favour in 1943. In January the siege of Leningrad ended, and in February the Germans surrendered at Stalingrad and were in retreat before the Soviet Armies. The Anglo-American carpet-bombing of German cities was under way. In the Pacific, Japanese aggression had been checked the previous May in the battle of the Coral Sea. The fear that the German war machine might use atomic bombs1 was abating. However, many Manhattan Project scientists found another fear was taking its place – that of a post-war nuclear arms race with worldwide proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Physicists had little doubt in 1944 that the bombs would test successfully, though the first test was not until 16 July 1945. In the Los Alamos Laboratory there was a race against the clock to assemble the bombs. It is perhaps remarkable that in spite of Germany’s imminent defeat, and the fact that it was common knowledge that Japan did not have the resources needed for atomic bomb manufacture, 2 few lab workers questioned whether they should continue work on the bombs. Joe Rotblat, the president of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs and a recipient of the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize, was a notable exception (see http://www.pugwash.org/award/Rotblatnobel.htm and http://www.nobel.se/peace/laureates/1995/rotblat-cv.html). Richard P Feynman, in an interview with the BBC shortly before his death, was asked how he felt about his participation in the effort, and rather ruefully replied that in the race against time he forgot to think about why he joined it.

At the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory (Met Lab), the pace of work was less intense. The major problems there were largely solved, and scientists and engineers began to discuss uses for nuclear energy in the post-war world. Realizing the devastation that nuclear weapons could cause, and that they could be made and delivered much more cheaply than conventional weapons of the same power, scientists tried to inform policy makers that the ideas underlying the Manhattan Project could not be kept secret, and that many nations and non-governmental entities would be able to make atomic bombs if fissionable material were available. Prominent among these were Leo Szilard and James A Franck. In their view, international control of fissionable materials was needed. There was discussion of forgoing even a test detonation of the bomb, and then a recommendation that it be used in an uninhabited area to demonstrate its power. They were concerned that actual military use would set a dangerous precedent and compromise the moral advantage the US and Britain might have to bring about international agreements to prevent the use of nuclear energy for weapons of war. Eventually they expressed these views in a report for the secretary of war and President Truman, now famous as the Franck Report (Stoff et al. 1991, 49). The report was classified top secret when first submitted, and only declassified years later. Various versions of it have now been published (Grodzins and Rabinowitch 1963; Smith 1965; Dannen 1995).

As the Manhattan Project went forward, some scientists in its leadership became prominent advisers in high government circles. Contrary to the Franck Report proposals, they advised immediate military use of the bombs. However, these scientists, in particular Arthur H Compton and J Robert Oppenheimer, actually mediated between their colleagues – who wished to deny the US and Britain the overwhelming political advantage sole possession of atomic bombs would bring – and political leaders such as Winston Churchill and James F Byrnes, Truman’s secretary of state, who wished to have this advantage. In the case of Oppenheimer, it is unclear where his sympathies lay, and this article has no light to shed on that. In the case of Compton, his sympathy with the nationalist goals of government officials is clear from in his own writings. He had a political philosophy markedly different from that of the Franck group. In his book, Atomic Quest (Compton 1956), he wrote: “In my mind General Groves3 stands out as a classic example of the patriot. I asked him once whether he would place the welfare of the United States above the welfare of mankind. ‘If you put it that way,’ the General replied, ‘there is only one answer. You must put the welfare of man first. But show me if you can,’ he added, ‘an agency through which it is possible to do more for the service of man than can be done through the United States.'”

Bohr, Roosevelt, Churchill and Einstein

Niels Bohr was deeply concerned about a predictable post-war nuclear arms race. In 1944 he urged Manhattan Project leaders and government officials, including President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, to consider open sharing with all nations, including the Soviet Union, the technology to lay the groundwork for international control of atomic energy. Felix Frankfurter arranged an interview with Roosevelt, who listened sympathetically and suggested they find out what the Prime Minister had to say about this. Bohr then went with his son to London and met with Churchill, who angrily rejected Bohr’s suggestion (Gowing 1964). Churchill prevailed, and at their September 1944 Hyde Park meeting Roosevelt and Churchill signed an aide-mémoire rejecting Bohr’s proposal. 4 Albert Einstein learned of Bohr’s failed efforts, and suggested they could take steps on their own and inform leading scientists whom they knew in key countries. 5 Bohr felt they should abide by wartime security restrictions and not do this.

The decision to drop the bombs

John A Simpson, a young Met Lab physicist, later recalled that “the wartime scientists and engineers recognized early what the impact of the release of nuclear energy would mean for the future of society and grappled with the question from 1944 onward…I was unaware that James Franck, Leo Szilard and others at the senior level already were exploring these questions deeply. Under the prevailing security conditions the younger scientists had not had an opportunity to become acquainted with these higher-level discussions” (Simpson 1981). These younger scientists organized seminars and discussions despite US Army orders that they meet only in twos and threes6, and later joined Szilard, Franck and others at the senior level. Eugene Rabinowitch prepared summary documents (Smith 1965). There were two main areas of concern: the urgent question of bombing a Japanese city; and the international control of fissionable materials and the problem of inspection and verification of agreements. Considerations and conclusions can be found in the Franck Report, and some are discussed below.

Undoubtedly aware of the Bohr meetings with Roosevelt and Churchill, Szilard tried to see Roosevelt to urge that the long-range consequences of the use of nuclear weapons should be taken into account alongside immediate military expediency. He enlisted his friend Einstein’s help in getting an appointment.7 Einstein wrote to Roosevelt urging him to meet Szilard immediately, saying: “I have much confidence in Szilard’s judgement.” Szilard’s memo, prepared in March 1945 for submission to the president, is remarkably prescient (Grodzins and Rabinowitch 1963). He foresaw our present predicament. He wrote: “The development of the atomic bomb is mostly considered from the point of view of its possible use in the present war…However, their role in the years that follow can be expected to be far more important, and it seems the position of the United States in the world may be adversely affected by their existence…Clearly, if such bombs are available, it is not necessary to bomb our cities from the air in order to destroy them. All that is necessary is to place a comparatively small number of such bombs in each of our major cities and to detonate them at some later time. The United States has a very long coastline which will make it possible to smuggle in such bombs in peacetime and to carry them by truck into our cities. The long coastline, the structure of our society, and our very heterogeneous population may make effective control of such ‘traffic’ virtually impossible.” Roosevelt died on 12 April, the letter from Einstein unopened on his desk.

After Roosevelt died Szilard tried, through an acquaintance with connections in Kansas City, to see President Truman. He was given an appointment with James F Byrnes, Truman’s designated secretary of state. He brought his memo to Byrnes and tried to discuss the importance of an international agreement to control nuclear energy. He did not get a sympathetic hearing, later recalling that “Byrnes was concerned about Russia’s having taken over Poland, Romania and Hungary, and…thought that the possession of the bomb by America would render the Russians more manageable” (Dannen 1995). Leaving the meeting, he said to Harold Urey and Walter Bartky, who had accompanied him: “The world would be much better off if Jimmy Byrnes had been born in Hungary and become a physicist and I had been born in the United States and become secretary of state.”

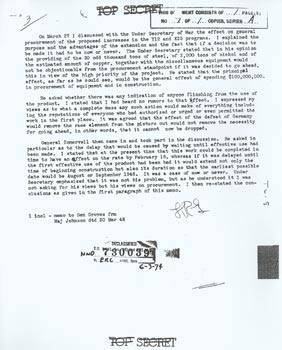

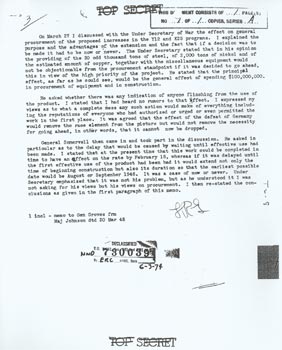

Germany’s surrender on 8 May 1945 had little effect on planning the atomic bomb drops. Several historians who have made extensive study of the documentary evidence have concluded that the use of the bomb in Europe was never systematically considered (Stoff et al. 1991; Dannen 1995; Sherwin 1975). No mention is found of a drop in Germany or in Europe. On the other hand, documents indicate a common expectation that Japanese forces would be targeted. The minutes of the Military Policy Committee meeting of 5 May 1943 state: “The point of use of the first bomb was discussed and the general view appeared to be that its best point of use would be on a Japanese fleet concentration…it was pointed out that the bomb should be used where, if it failed to go off, it would land in water of sufficient depth to prevent easy salvage. The Japanese were selected as they would not be so apt to secure knowledge from it as would the Germans” (Sherwin 1975). Another indication that the focus was Japan is in the 1944 aide-mémoire of Roosevelt and Churchill where they agreed that “when a ‘bomb’ is finally available, it might perhaps, after mature consideration, be used against the Japanese” (Stoff et al. 1991, 26). General Groves’ record of a discussion he had with the undersecretary of war on 27 March 1945 is also of interest in this regard. He says he was asked “whether there was any indication of anyone flinching from the use of the [atomic bomb]. I stated that I had heard no rumours to that effect. I expressed my views as to what a complete mess any such action would make of everything including the reputations of everyone who had authorized or urged or even permitted the work in the first place. It was agreed that the effect of the defeat of Germany would remove the race element from the picture but would not remove the necessity for going ahead” (this now declassified memo was obtained from the National Archives; see Dannen 1995).

After Roosevelt’s death a committee was formed by the secretary of war Henry L Stimson to directly advise the president and Congress on issues relating to both civilian and military use of nuclear energy. It was called the Interim Committee because it was constituted without the knowledge of Congress. The members of the committee were Secretary Stimson (chair); Vannevar Bush, director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development; James Conant, president of Harvard University and director of defense research; Karl Compton, president of MIT; assistant secretary of state William Clayton; undersecretary of the Navy Ralph Bard; and secretary of state-to-be Byrnes. This committee appointed an advisory Scientists Panel consisting of Oppenheimer (chair), Enrico Fermi, E O Lawrence and Arthur Compton. The Interim Committee seems to have played an important, if not crucial, role in President Truman’s decision to use the bombs. Notes of its 1 June meeting (Stoff et al. 1991, 44) record that “Mr Byrnes recommended and the committee agreed that the secretary of war be advised that, while recognizing that the final selection of the target was essentially a military decision, the present view of the committee was that the bomb should be used against Japan as soon as possible.” Historians believe Truman met with Byrnes later that day and made this decision (Rhodes 1986).8

The Scientists Panel was present at the previous 31 May Interim Committee meeting where it was agreed that the scientists inform colleagues about the committee (Stoff et al. 1991, 41). Arthur Compton told senior staff in the Met Lab about the committee but seems not to have informed them that the committee would advise immediate wartime use (Compton 1956; Smith 1965). Perhaps he didn’t know, but that seems unlikely – his brother Karl was on the committee.

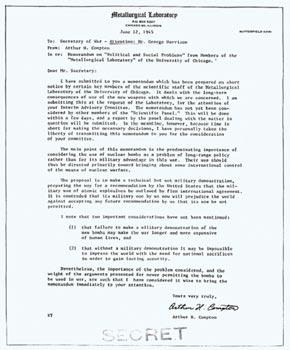

The Franck Report was then written, dated 11 June 1945, and sent to Stimson and the Interim Committee. The preamble reads: “We felt it our duty to urge that the political problems arising from the mastering of atomic power be recognized in all their gravity, and that appropriate steps be taken for their study and the preparation of necessary decisions. We hope that the creation of the committee by the secretary of war to deal with all aspects of nucleonics indicates that these implications have been recognized by the government. We feel that our acquaintance with the scientific elements of the situation and prolonged preoccupation with its worldwide implications imposes on us the obligation to offer to the committee some suggestions as to the possible solution of these grave problems.” As regards immediate military use of the bombs, they disagreed with the Interim Committee’s advice to the president. They found “use of nuclear bombs for an early, unannounced attack against Japan inadvisable. If the United States would be the first to release this new means of indiscriminate destruction upon mankind, she would sacrifice public support throughout the world, precipitate the race of armaments, and prejudice the possibility of reaching an international agreement on the future control of such weapons. Much more favourable conditions for the eventual achievement of such an agreement could be created if nuclear bombs were first revealed to the world by a demonstration in an appropriately selected uninhabited area…To sum up, we urge that the use of nuclear bombs in this war be considered as a problem of long-range national policy rather than military expediency, and that this policy be directed primarily to the achievement of an agreement permitting an effective international control of the means of nuclear warfare.”

The authors were the Committee on Political and Social Problems of the Metallurgical Laboratory of the University of Chicago, better known as the Franck Committee. The members were Franck (chair), Donald J Hughes, J J Nickson, Rabinowitch, Glenn T Seaborg, J C Stearns and Szilard. The report is a lengthy, deliberative document consisting of five sections: Preamble; Prospectives of Armament Race; Prospectives of Agreement; Methods of Control; and Summary. Compton, director of the Met Lab, submitted the report to Stimson with a covering memo dated 12 June (Stoff et al. 1991, 48). Reading this memo, one cannot help but think that Compton’s intention was to obviate the effect of the report.

The memo suggested that the report need not be given much attention, assuring the secretary that the Scientists Panel would consider it and report back in a few days. Indeed, the panel’s report was submitted four days later. It disagrees with the recommendations of the Franck Report and supports the advice the Interim Committee had given. It is relatively brief, essentially reiterating the two considerations Compton erroneously claims were not mentioned in the Franck Report.9 Entitled “Recommendations on the Immediate Use of Nuclear Weapons”, it begins: “You have asked us to comment on the initial use of the new weapon,” and goes on to say: “We see no acceptable alternative to direct military use” (Stoff et al. 1991, 51). Given Compton’s views, and given Oppenheimer’s deep involvement with General Groves and the Target Committee, it is not surprising that the Scientists Panel endorsed the immediate use of the bomb.10

Arthur Compton’s political philosophy was very different from that of the Franck group. He believed that every effort should be taken by the United States to “keep nuclear weapons out of the hands of totalitarian regimes.” In 1946 he suggested how to keep the peace in an essay entitled “The Moral Meaning of the Atomic Bomb”, published in the collection Christianity Takes a Stand. He wrote: “It is now possible to equip a world police with weapons by which war can be prevented and peace assured. An adequate air force equipped with atomic bombs, well dispersed over the earth, should suffice…we must work quickly. Our monopoly of atomic bombs and control of the world’s peace is short-lived. It is our duty to do our utmost to effect the establishment of an adequate world police…This is the obligation that goes with the power God has seen fit to give us” (Johnston 1967). Some might conjecture that this sharp difference in political philosophy reflects a European, as opposed to an American, approach to the problem. Some Americans, like Compton, may have had a more naïve and trusting view of their government than Europeans tend to do, but it is worth noting that there were many Americans who believed, as did the Franck group, that international agreements were necessary to keep the peace.11

Massive loss of life was expected in the Allies’ invasion of the Japanese islands. The invasion was due to begin on 1 November. In June there was still fighting on Okinawa, but it was drawing to a close. Major military actions planned for summer and autumn were blockade and continuation of the bombing campaign. “Certain of the United States commanders and representatives of the Survey [US Strategic Bombing Survey] who were called back from their investigations in Germany in early June 1945, for consultation, stated their belief that by the coordinated impact of blockade and direct air attack, Japan could be forced to surrender without invasion” (US Strategic Bombing Survey 1946). Nevertheless, following the Interim Committee’s advice for immediate military use, the bombs were dropped on 6 and 9 August. Little is said about the drops having been made as soon as the bombs were ready rather than later in the summer or early autumn. Whether or not the bombs were necessary to force a Japanese surrender prior to invasion is still being debated by historians (Nobile 1995; Bernstein 1976). The Strategic Bombing Survey (US Strategic Bombing Survey 1946) concluded that: “Certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.” The Soviet Union had massed a very large and well-equipped army on the Manchurian border in the summer of 1945, and on 8 August, precisely three months after VE day, declared war on Japan in accordance with the 11 February 1945 Yalta agreement, which states that: “The Soviet Union, the United States and Great Britain agreed that in two or three months after Germany has surrendered and the war in Europe is terminated, the Soviet Union shall enter into war against Japan on the side of the Allies.” The Soviet invasion of occupied Korea and Manchuria began on 9 August, the day Nagasaki was bombed.

It seems that there would have been time before the planned 1 November invasion to attempt to get the Japanese to surrender with a demonstration of the bomb’s power, as the Franck Committee suggested. However, this would have been much more complicated than a drop on a city. In his 1960 interview (Dannen 1995), Szilard said: “I don’t believe staging a demonstration was the real issue, and in a sense it is just as immoral to force a sudden ending of a war by threatening violence as by using violence. My point is that violence would not have been necessary if we had been willing to negotiate. After all, Japan was suing for peace.”12

There are many explanations offered for the immediate military use of the bombs. P M S Blackett concluded that it was a clever and highly successful move in the field of power politics (Blackett 1949). I tend to agree with him, especially in light of the post-war years and of the events of today. It is unlikely that the Franck group believed they could influence the course of events. Nevertheless, they tried very hard to have their voices heard. Many felt along with Leo Szilard that “it would be a matter of importance if a large number of scientists who have worked in this field went clearly and unmistakably on record as to their opposition on moral grounds to the use of these bombs in the present phase of the war” (Dannen 1995). The scientists’ main message, unheeded then and very relevant now, is that worldwide international agreements are needed to provide for inspection and control of nuclear weapons technology. Their memoranda and reports remain as historic documents eloquently testifying to their concern.

Further reading

B J Bernstein (ed.) 1976 The Atomic Bomb: the Critical Issues (Little, Brown & Co, Boston).

P M S Blackett 1949 Fear, War, and the Bomb (McGraw-Hill Book Co, New York). Blackett received a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1948 for his work on cosmic rays.

A H Compton 1956 Atomic Quest (Oxford University Press, New York).

G Dannen 1995 http://www.dannen.com/szilard.html. This is a very rich website on which a selection of historical documents from Dannen’s archive is posted. An interview with Szilard published in US News & World Report on 15 August 1960 is reproduced verbatim.

M Gowing 1964 Britain and Atomic Energy 1939-1945 (Macmillan & Co, London).

M Grodzins and E Rabinowitch (eds) 1963 The Atomic Age: Scientists in National and World Affairs in Articles from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 1945-1962 (Basic Books, New York). Szilard’s memo can also be found as document 38 in Stoff et al. 1991 and is on the Web (Dannen 1995).

M Johnston (ed.) 1967 The Cosmos of Arthur Holly Compton (Alfred A Knopf Inc, New York).

P Nobile (ed.) 1995 Judgement at the Smithsonian (Marlowe & Co, New York).

R Rhodes 1986 The Making of the Atomic Bomb (Simon and Schuster, New York).

M J Sherwin 1975 A World Destroyed (Alfred A Knopf Inc, New York). See footnote on p209 of First Vintage Books edition (January 1977).

J A Simpson 1981 Some personal notes The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 37:1 26.

A K Smith 1965 A Peril and a Hope (University of Chicago Press, Chicago).

M B Stoff, J F Fanton and R H Williams (eds) 1991 The Manhattan Project: a Documentary Introduction to the Atomic Age (Temple University Press, Philadelphia). There are 95 documents reproduced in this book; many, including the Franck Report, were classified secret or top secret and declassified years after the end of the war. In this article they are referenced by the document number given by Stoff et al. (for example, the Franck Report is document 49). The Franck Report can also be found in Smith 1965, Grodzins and Rabinowitch 1963 and Dannen 1995.

US Strategic Bombing Survey 1946 (Washington DC Government Printing Office).

*This article is adapted from “Fermi and Szilard” (http://xxx.lanl.gov/html/physics/0207094) by the author.

<textbreak=Footnotes>1. Though nuclear more accurately describes the energy source, the term atomic rather than nuclear was chosen by Henry deWolf Smyth in the first published description of the work of the Manhattan Project, 1945 Atomic Energy for Military Purposes (US Government Printing Office, Washington DC). He explained this choice was because atomic would be more cognitive to the general public.

2. Nishina, Hagiwara and other Japanese physicists were working on the problem, but it was realized inter alia that hundreds of tonnes of uranium ore and a tenth of Japanese electrical capacity would be needed for 235U separation (Rhodes 1986 pp 457-459).

3. Brigadier General Leslie R Groves was the US Army general in charge of the Manhattan Project.

4. The aide-mémoire signed by the two heads of state states that “the suggestion that the world should be informed regarding Tube Alloys [the British term for the bomb project], with a view to an international agreement regarding its control and use, is not accepted” (Stoff et al. 1991, 26).

5. See Gowing 1964; also F Jerome 2002 The Einstein File (St Martin’s Press, New York).

6. This order was evaded by scheduling these meetings in a small room with a large anteroom. While a scheduled meeting took place, people waiting in the anteroom could have a discussion.

7. In 1939 Szilard had enlisted Einstein’s help in obtaining government funding for studies of neutron-induced uranium fission, and the result was the famous 2 August 1939 letter from Einstein to President Roosevelt informing him of the possibility of an atomic bomb.

8. Stimson recorded in his diary for 6 June a conversation with Truman indicating that the decision had been already made (Stoff et al. 1991, 45).

9. It is clear the Franck Committee was fully aware of Compton’s point (1), had given it serious consideration and concluded that in the long run many more lives could be saved if effective international, worldwide control of nuclear power were achieved. Compton’s important consideration (2) is, remarkably, a weak statement of a concern dealt with in depth in the Frank Report (figure 1).

10. Compton reports that Lawrence was reluctant to go along with this advice but was persuaded to do so (Compton 1956).

11. Among them were Robert Wilson, Glenn Seaborg, Katherine Way and others who signed Szilard’s petition to the president (Dannen 1995). See http://www.dannen.com/decision/45-07-17.html.

12. According to the Strategic Survey Report (US Strategic Bombing Survey 1946): “Early in May 1945 the Supreme War Direction Council [of Japan] began active discussion of ways and means to end the war, and talks were initiated with Soviet Russia, seeking her intercession as mediator.”