Modern Cosmology by Scott Dodelson, Academic Press. ISBN 0122191412, £39.95 ($70).

Particle Astrophysics by Donald Perkins, Oxford University Press. Hardback ISBN 0198509510, £44.95 ($74.50). Paperback ISBN 0198509529, £22.95 ($39.50).

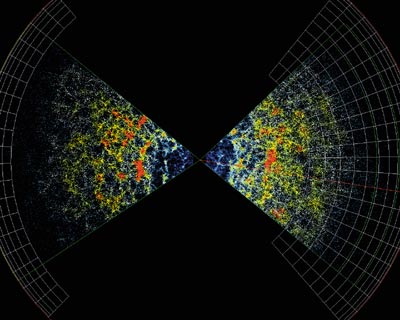

It is widely and justifiably stated that we are in a golden age for cosmology. Certainly, in just the past five years our knowledge of the universe has increased in leaps and bounds by virtue of new data concerning the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the study of very distant Type-1a supernovae (SNe1a), and surveys of large-scale structure (LSS). Cosmic parameters that five years ago were uncertain by a factor of two, are now known to a few per cent. The cosmic concordance of the three data sets for CMB, SNe1a and LSS leads us to our present understanding of the universe as flat with a total energy very close to the critical density, and containing (with quite small errors) 4% baryonic material, 23% nonbaryonic dark matter and 73% dark energy.

Other areas of fundamental theoretical physics have also made progress. In particular, again in the past five years, the Standard Model of particle phenomenology has been shown to be inadequate by the experimental demonstration of neutrino masses. Particle phenomenology and theoretical cosmology have become even more closely intertwined. String theory, though not yet supported by any experimental test, is a constant source of ideas concerning both particle phenomenology and the principal issues of theoretical cosmology. It is an interesting question whether the first support for string theory will come from the very small or the very large.

If we go back further, say 20 years, cosmological data were so inaccurate that the field was treated with some condescension by particle theorists who were accustomed to reproducible precision data from the large accelerators. This situation gradually changed due to the heroic efforts of people like the late Dave Schramm. Now, with the release by NASA of the WMAP data on CMB in February 2003, we have entered what can be called, without hesitation, the era of precision cosmology. In a book on precision cosmology, after the necessary introduction to the mathematics of an expanding space-time, the topics that could very reasonably be included are: 1. cosmic microwave background, 2. nucleosynthesis, 3. inflation, 4. dark matter, 5. dark energy, 6. structure formation, and 7. black holes and other extreme events such as supernovae and, what may be a subset, gamma-ray bursters. It is with this preconceived menu in mind that I review these two books.

Modern Cosmology by Scott Dodelson is intended for beginning graduate students. This book is very up to date and gives excellent treatments of structure formation, and especially of the CMB, including its polarization and details of its statistical analysis. This provides what is the most complete such description in any textbook. The topic of weak gravitational lensing is also handled well. The young author is an active researcher in theoretical cosmology whose enthusiasm for the subject is evident throughout, and whose selection of topics reflects his areas of greatest expertise. The inclusion of many worked examples will make this book a very good choice for a graduate course.

For researchers, the treatment of data analysis will be particularly valuable. For both CMB, from WMAP and the future more data intensive Planck mission, and for LSS from the Sloan Digital Sky and 2dF surveys, as well as even larger galaxy surveys in the future, the quality and quantity of the raw data set are such that straightforward algorithms are too slow even with the fastest available computers. Thus considerable creativity and intelligence are needed to optimize such an analysis. It is interesting that a similar situation must exist for raw data from high-energy particle colliders such as from the Tevatron at Fermilab and the future LHC collider at CERN. It is therefore very welcome that, for both CMB and galaxy surveys, Dodelson leads us masterfully through the likelihood function and sophisticated mathematical techniques for its evaluation.

A comparison of Dodelson’s book according to my menu of topics, reveals that topics 1 and 6 are thoroughly treated, while items 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 are only relatively briefly described. Thus the treatment is very strong in only some of the areas. To be fair, the author is well aware of this and provides copious and generous references to other books, which should fill in the gaps.

One minor complaint is that the typesetting is not adequately checked, for example the headings of subsections 7.2.2 and 7.3.2 are at the foot of the previous page. But this is nitpicking and I liked this book and believe that it, together with the other referenced publications, could form the basis for a very interesting postgraduate course in cosmology, as well as being useful for active researchers to have in their personal library.

Donald Perkins’ Particle Astrophysics is intended for the different audience of advanced undergraduates. The author is a senior high-energy experimentalist, and two of the seven chapters are on topics in particle theory. This book contains elementary discussions of expanding space-time, dark matter, dark energy and structure formation. There is also a chapter each on cosmic rays, the author’s forte, and stellar evolution. One attractive feature of Perkins’ book is that each chapter ends with a concise summary of its most important items. Perkins writes exceptionally clearly and includes a significant number of worked examples, making this an ideal textbook for use in a junior or senior course that introduces particle theory and cosmology and their strong interrelationship.