Most developing countries experience great difficulties because of adverse economic conditions and political instability, which means they lag behind in scientific and technological development. Building science facilities can be very expensive, so there is the potential for an enormous gap between the rich and the poor. However, science has been quite successful in leap-frogging this gap, enabling scientists from developing countries to participate in many scientific activities. This has taken many forms, including the interaction between scientists by e-mail, and visits by senior scientists and graduate students. Large facilities have also opened their doors to scientists from economically disadvantaged countries, literature and equipment has been donated by both organizations and individuals, and conference access has been made available.

With the advent of the World Wide Web and the rapid exchange of information via the Internet, one might naively have thought that much of the gap between developed and developing nations would disappear, even if problems still persisted for those areas of science that need expensive facilities. However, access to information, peer reviewed or not, depends on having the appropriate hardware, i.e. a computer, and Internet connectivity, and there is a serious problem with access to the Internet in developing countries. Gaining access to a computer is more of a question of economics, and one that we will assume will somehow be overcome. In this article we will instead concentrate on the issue of Internet connectivity.

Most of the countries with the lowest income economies have or have had serious problems with bandwidth, as well as with the high cost of access to the Internet. The high cost of connectivity is mainly due to the monopolies that communication companies are able to establish in developing countries. These costs, added to the low bandwidth, do not allow scientists to have timely access to information. In addition, there is also the expense of scientific literature, which is often prohibitive.

In most cases scientists in basic research do not attach economic value to their product, and so are willing to share their knowledge with fellow scientists, independent of their nationality or race. In addition, many scientific publishing companies are run at least partially by scientists, and most are willing to allow those from disadvantaged countries to access their journals, despite the usual high prices. This has given birth to some very successful initiatives in areas such as medicine (HINARI – Health InterNetwork Access to Research Initiative), biology (PERI – Programme for the Enhancement of Research Information), agriculture, fishery and forestry (AGORA – Access to Global Online Research in Agriculture), and physics, mathematics and biology (eJDS – electronic Journals Delivery Service). These are run by the World Health Organization, the International Network for the Availability of Scientific Publications, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), respectively, in strict collaboration with major publishing companies and societies.

All these initiatives, even if they use different ways to access the sources of information, have a common characteristic: they allow scientists in the least-developed countries (individually, or through their libraries) to access the best and most appreciated literature in their fields. And in most cases this access is free.

Renowned Ghanaian scientist Francis Allotey, who is active in the politics of science in Ghana, has said: “We paid the price for not taking part in the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth century because we did not have the opportunity to see what was taking place in Europe. Now we see that information and communication technology (ICT) has become an indispensable tool. This time, we should not miss out on this technological revolution.”

Up until a year ago it was not clear, despite the efforts of many, whether bridging the digital divide with Africa would be feasible. However, at a recent meeting in Trieste, “Open Round Table on Developing Countries Access to Scientific Knowledge: Quantifying the Digital Divide”, we were able to see that some of the African countries had come up with very ingenious ideas to keep up with ICT. It is clear that Africa has decided to take Allotey’s words to heart, and has engaged in whatever may be necessary to bridge the technological divide. It is therefore more important than ever that the efforts to help them that have already begun do not stop; the results are there to see. If this ICT revolution is not to be missed, scientific institutions must keep up to date, and this in turn relies on the Internet connectivity of these institutions. But do they have it?

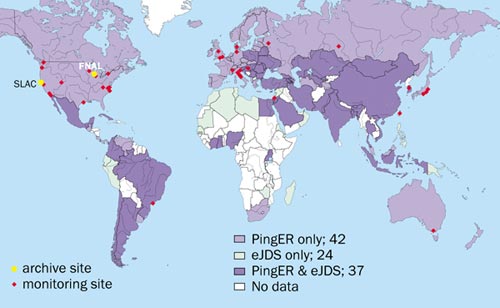

For the first time, at the same round table, Les Cottrell of SLAC, Warren Matthews of the Georgia Institute of Technology and Enrique Canessa of ICTP, Trieste, presented results on the connectivity of institutions in Third World countries, using measurements performed by the SLAC/PingER project. Figure 1 shows all the countries covered by this project, which measures the return time of an Internet packet between monitor sites and remote sites. Monitoring Internet connectivity or Internet performance in this way gives a good idea of trends – who is catching up, who is falling behind – and also allows a comparison of Internet performance with economic indicators. Since it is a quick way of measuring trends in ICT, decisions on investments can be made quickly enough to avoid irreversible damage.

The PingER project started some years ago to monitor Internet performance for data exchange in the large high-energy and nuclear-physics collaborations around the world. Recently, following an agreement with the ICTP and eJDS, the measurements have been extended to a selection of institutional hosts in developing countries, and are now available for around 80 countries.

Figure 2 shows throughputs in kilobytes per second as a function of time between January 1995 and January 2003. The measurements were made from SLAC in the US. The results show that Latin America, China and Africa, while at much lower levels of performance than the US (Edu), Canada and Europe, are keeping pace with these countries. Russia is quickly improving, but surprisingly India is lagging behind. This is a piece of information that should worry policy makers in India, as it is a country with a very well developed ICT. So why are their institutions behind? Part of the reason may be the choice of hosts being monitored in India, which are at academic and research institutions. But even so, this means that some institutions are very backward, with very poor connectivity.

The amount of data gathered is not enough to give a complete picture of the whole world, but it does show that the technology to monitor is there. Policy makers from developing countries can benefit from the data, since the information is freely available on the eJDS website (www.ejds.org). Moreover, it can also help when large funding agencies decide to invest in development, and will give an idea of the performance of the various countries. This measure of connectivity should be considered as a new variable in the complex field of economics.