In Vienna, Austria, in December 2001 the Nuclear Physics European Collaboration Committee (NuPECC) started to prepare a new long-range plan for nuclear physics in Europe. NuPECC’s goal was to produce “a self-contained document that reflects on the next five years and provides vision into the next 10-15 years”. The previous long-range plan had been published as a report, “Nuclear Physics in Europe: Highlights and Opportunities”, in December 1997.

NuPECC first defined the active areas of nuclear physics that were to be addressed. Working groups were formed, spanning all the subfields of nuclear physics and its applications: nuclear structure; phases of nuclear matter; quantum chromodynamics; nuclear physics in the universe; and fundamental interactions and applications. Convenors for each of these groups were appointed and two liaison members of NuPECC were assigned to each of them. The working groups were then asked to provide recommendations for possible future directions and a prioritized list of the facilities and instrumentation needed to address them.

The next step in the process was a town meeting, organized at GSI Darmstadt on 30 January – 1 February 2003, to discuss the long-range plan. Prior to this, the preliminary reports of the groups had been posted on the NuPECC website. The town meeting was well attended with around 300 participants, including many young scientists, and the following summarizes the general trends and exciting ideas about modern nuclear physics that were presented at the meeting and given in the report.

Progress in nuclear research

At a deeper level, nuclear physics is the physics of hadrons. Here, recent developments in lattice quantum chromodynamics (QCD) calculations have raised a great deal of interest in hadron spectroscopy. According to QCD, gluon-rich hadrons can be formed, as well as hybrid states of combinations of quark and gluonic excitations. There is also interest in quark dynamics, since in hadrons the polarization of gluons and the orbital angular momentum of quarks play an important role, together with a large transverse quark polarization. Nowadays the measurement of generalized parton distributions – which are generalizations of the usual distributions describing the momentum or helicity distributions of the quarks in the nucleon – receives much attention as the measurements will improve our knowledge of the structure of the hadron. Quark confinement and the study of phenomena in the non-perturbative regime of QCD will be addressed in future. Phase transitions of nuclear matter are being investigated in two regimes: at the Fermi energy, at which a liquid-gas phase transition is expected, and at very high energies and/or densities where a quark-gluon plasma (QGP) is expected. In the first phase transition interesting isospin effects turn out to play a role in the formation of exotic isotopes, whereas at the second phase transition the deconfinement of quarks is expected at very high temperatures and colour superconductivity at low temperatures and very high densities.

A long-term and fundamental goal of nuclear physics is to explain low-energy phenomena starting from QCD. In a first step, the connection could be made through QCD-motivated effective field theories. This should go hand in hand with experimental investigations that allow tests of these models. Recently, new developments have taken place, raising interest in nuclear structure, and besides the development of equipment and refined detection methods, it is now possible to use exotic beams of unstable nuclei. Furthermore, due to the increase in computing capacity, ab initio calculations with two- and three-body forces up to mass 12 can be performed. Experimentally, it is now possible to broaden the research field of the 300 stable nuclei to the approximately 6000 atomic nuclei that are predicted to exist. This means that a number of questions can now be addressed, such as what happens in extreme conditions of the neutron to proton (N/Z) ratio, at a high excitation energy, at an extreme angular momentum, or at a very heavy mass – that is, at considerably more extreme conditions than those we have investigated so far. Phenomena to be addressed here include neutron halo structures, super-heavy elements, new magic numbers, hyperdeformation and many other exotic forms of atomic nuclei.

In the past 20 years nuclear astrophysics has developed into an important subfield of nuclear physics. It is a truly interdisciplinary field, concentrating on primordial and stellar nucleosynthesis, stellar evolution, and the interpretation of cataclysmic stellar events such as novae and supernovae. It combines astronomical observation and astrophysical modelling with research into meteoritic anomalies, and with measurements and theory in nuclear physics. With the use of new methods, as well as the availability of radioactive-ion-beam (RIB) accelerators, astrophysically relevant nuclear reactions are already being measured. In future, this research will be intensified with the new generation of RIB facilities.

In the past, research on symmetries and fundamental interactions (and the physics beyond the Standard Model) has made large steps with the development of techniques that facilitate precision measurements. In this subfield, research on the properties of neutrinos (mass measurement), time-reversal and charge-parity violation (through measurements of electric-dipole moments of molecules, atoms and nucleons as well as correlations between electrons and neutrinos in ß-decay), and the determination of fundamental constants, is in progress.

Finally, there has been progress in the applications of nuclear-physics techniques and methods. These cross over into several disciplines, such as life sciences, medical technology, environmental studies, archaeology, future energy supplies, art, solid-state and atomic physics, and civilian safety.

Research facilities

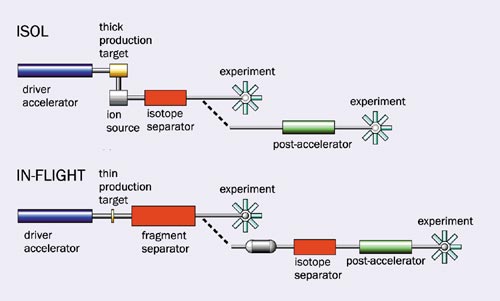

Several new research facilities are now being developed or built. The most ambitious is the International Accelerator Facility for Beams of Ions and Antiprotons (IAFBIA) in Darmstadt (currently GSI) (see IAFBIA box). This will be available for experiments after 2010. For nuclear structure and related studies with extreme N/Z ratios, RIB facilities are required and can be realized by means of the in-flight fragmentation (IFF) technique, as aimed at with the IAFBIA, or the isotope-separation online (ISOL) method (see figure 1). In Europe, a plan to build the European ISOL (EURISOL) facility, which would be ready after 2013, exists, and intermediate to this are the ISOL facilities already operational at CERN, GANIL and Louvain-la-Neuve, and the upgrades at REX-ISOLDE and SPIRAL2, as well as the future facilities SPES in Legnaro and MAFF in Munich.

Recommendations

The first of NuPECC’s recommendations is to exploit fully the existing and competitive lepton, proton, stable isotope and radioactive ion-beam facilities and instrumentation. In addition to their physics-research potential, they will serve as important training sites and facilities where major beam-production development and detector R&D can be performed in the next 5 to 10 years. In its previous long-range plan, NuPECC gave high priority to the ALICE experiment at CERN, which has an extensive programme to investigate QGP in the framework of the large and active heavy-ion programme at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in the near future. A huge European effort is already underway to build the ALICE detector in time for the LHC. In accordance with the high priority given to ALICE in the previous long-range plan, NuPECC strongly recommends its timely completion to allow early and full exploitation at the start of the LHC.

Support of the university-based nuclear-physics groups, including their local infrastructure, is seen by NuPECC as essential for the success of the programmes at the present facilities and at future large-scale projects. Furthermore, NuPECC recommends that efforts should be taken to strengthen local theory groups in order to guarantee the development needed to address the challenging basic issues that exist or may arise from new experimental observations. NuPECC also recognizes the positive role played by the ECT* centre in Trento in nuclear theory, especially in its mission of strengthening unifying contacts between nuclear and hadron physics. In addition, NuPECC recommends that efforts to increase literacy in nuclear science among the general public be intensified.

Priorities for the future

The specific recommendations and priorities follow on from the new experimental facilities and advanced instrumentation that have been proposed, or are under construction, to address the challenging basic questions posed by nuclear science. NuPECC supports, as the highest priority for a new construction project, the building of the IAFBIA. This international facility (see IAFBIA box) will provide new opportunities for research in the different subfields of nuclear science. Envisaged for producing high-intensity radioactive ion beams using the IFF technique, the facility is highly competitive, even surpassing in certain respects similar facilities that are either planned or under construction in the US or in Japan. With the experimental equipment available at low and high energies, and at the New Experimental Storage Ring with its internal targets and electron collider ring, the facility will be a world leader in research in nuclear structure and nuclear astrophysics, in particular for research performed with short-lived exotic nuclei far from the valley of stability. The high-energy, high-intensity stable heavy-ion beams will facilitate the exploration of compressed baryonic matter with new penetrating probes. The high-quality cooled antiproton beams in the High-Energy Storage Ring, in conjunction with the planned detector system, PANDA, will provide the opportunity to search for the new hadron states that are predicted by QCD, and to explore the interactions of the charmed hadrons in the nuclear medium. In short, this facility is broadly supported since it will provide almost all fields of nuclear science with new research opportunities.

After the construction of IAFBIA, NuPECC recommends the highest priority to be the construction of the advanced ISOL facility, EURISOL. The ISOL technique for producing radioactive beams has clear complementary aspects to the IFF method. First-generation ISOL-based facilities have produced their first results and have been shown to work convincingly. The next-generation ISOL-based RIB facility EURISOL aims at increasing, beyond 2013, the variety of radioactive beams and their intensities by orders of magnitude over what is available at present for various scientific disciplines, including nuclear physics, nuclear astrophysics and fundamental interactions. EURISOL will employ a high-power (several MW) proton/ deuteron (p/d) driver accelerator. A large number of possible projects, such as a neutrino factory, an antiproton facility, a muon factory and a neutron spallation source, may benefit from the availability of such a p/d driver, and synergies with closely and less closely related fields of science are abundant. Considering the wide interest in such an accelerator, NuPECC proposes joining with other interested communities to do the Research and Technological Development (RTD) and design work necessary to realize the high-power p/d driver in the near future.

NuPECC also gives a high priority to the installation at the Gran Sasso underground laboratory of a compact, high-current 5 MV accelerator for light ions, equipped with a high-efficiency 4π array of germanium detectors. Such a facility will enhance the uniqueness of the present facility at Gran Sasso, and its potential to measure astrophysically important reactions down to relevant stellar energies.

On a longer timescale, the full exploration of non-perturbative QCD, e.g. unravelling hadron structure and performing precision tests of various QCD predictions, will require a high-intensity, high-energy lepton-scattering facility. NuPECC considers physics with a high-luminosity multi-GeV lepton-scattering facility to be very interesting and of high scientific potential. However, the construction of such a facility would require worldwide collaboration, so NuPECC recommends that the community pursues this research from an international perspective, incorporating it into any existing or planned large-scale facilities.

To exploit the current and future facilities fully and most efficiently, advanced instrumentation and detection equipment will be required to carry on the various programmes. The AGATA project for the construction of a 4π array of highly segmented germanium detectors for γ-ray tracking will benefit research programmes in the subfields of nuclear science at the various facilities in Europe. NuPECC gives its full support to the construction of AGATA, and recommends that the R&D phase be pursued with vigour.

•For more information about NuPECC, see www.nupecc.org.