In the 1990s, the GALLEX and SAGE experiments studied solar electron neutrinos using large tanks of gallium. Every few days a neutrino would transform a neutron into a proton, and every few weeks the experimenters would count the resulting germanium atoms using radiochemical techniques. To control systematic uncertainties in these difficult experiments, they also exposed the detectors to well-understood radioactive sources of electron neutrinos. But both experiments reported 20% fewer electron neutrinos from radioactive decay than expected.

Thus was born the gallium anomaly, which was carefully checked and confirmed by SAGE’s successor, the BEST experiment, as recently as 2022. The most tempting explanation is the existence of a new particle: a “sterile” neutrino flavour that doesn’t interact via any Standard Model interaction. Neutrino oscillations would transform the missing 20% of electron neutrinos into undetectable sterile neutrinos. It would nevertheless have remained invisible to LEP’s famous measurement of the number of neutrino flavours as it would not couple to the Z boson.

Out the window

This interpretation has been in tension with neutrino-oscillation fits for some time, but a new measurement at the KATRIN experiment likely excludes a sterile-neutrino explanation of the gallium anomaly, says Patrick Huber (Virginia Tech). “There was a strong hint of that from solar neutrinos, but the KATRIN result really nails this window shut. That is not to say the gallium anomaly went away; the experimental evidence here is firm and stands at more than five sigma significance, even under the most conservative assumptions about nuclear cross sections and systematics. So this still requires an explanation, but due to KATRIN we now know for sure it can’t be a vanilla sterile neutrino.”

KATRIN’s main objective is to measure the mass of the electron neutrino (CERN Courier January/February 2020 p28). Though neutrino oscillations imply that the particle is massive, its mass has thus far proved to be below the sensitivity of experiments. The KATRIN experiment, based at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany, seeks to remedy this with precise observations of the beta decay of tritium. The heavier the electron neutrino, the lower the maximum energy of the beta-decay electrons. Though KATRIN has not yet been able to uncover evidence for the tiny mass of the electron neutrino, the much larger mass of any sterile neutrino able to explain the gallium anomaly would have made itself felt in precise observations of the endpoint of the energy spectrum of beta-decay electrons thanks to mixing between the neutrino flavours.

After the new KATRIN analysis, the best fit of the sterile neutrino from the gallium anomaly is excluded at 96.6% confidence

“A sterile neutrino would manifest itself as a model-independent kink-like distortion in the beta-decay spectrum, rather than as a deficit in the event rate,” explains lead analyst Thierry Lasserre of the Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysik, in Heidelberg, Germany. “After the new KATRIN analysis, including 36 million electrons in the last 40 electron volts below the endpoint, the best fit of the sterile neutrino from the gallium anomaly is excluded at 96.6% confidence.”

Though heavy sterile neutrinos remain a well motivated completion of the Standard Model of particle physics with the potential to solve problems in cosmology, light sterile neutrinos struck out a second time in the same volume of Nature last month, thanks to a new measurement at the MicroBooNE experiment at Fermilab, near Chicago.

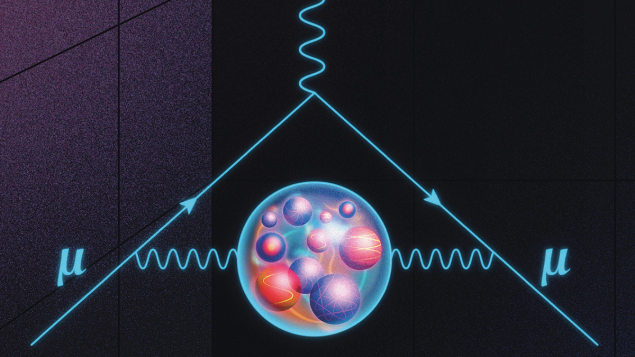

The MicroBooNE collaboration was following up on a persistent anomaly uncovered by their sister experiment, MiniBooNE, which was itself following up on the infamous LSND anomaly of 2001 (CERN Courier July/August 2020 p32). Both experiments had reported an excess of electron neutrinos in a beam of muon neutrinos generated using a particle accelerator. Here, the sterile-neutrino explanation would be more subtle: muon neutrinos would have to oscillate twice, once into sterile neutrinos and then into electron neutrinos. Using a bespoke liquid-argon time projection chamber, the MicroBooNE collaboration excludes the single-light-sterile-neutrino interpretation of the LSND and MiniBooNE anomalies at 95% confidence.

“The MicroBooNE result is just confirming what we knew from global fits for a long time,” clarifies Huber. “We cannot treat the appearance of electron neutrinos in a muon neutrino beam as a two-flavour problem if a sterile neutrino is involved – if we accept this simple fact of quantum mechanics then LSND and MiniBooNE’s excess of electron neutrinos cannot be due to mixing with a sterile neutrino since the corresponding disappearance of electron and muon neutrinos has not been observed.”

One sterile-neutrino anomaly remains unmentioned, the reactor anomaly, but it has already evaporated into statistical insignificance thanks to new experiments and careful modelling of the flux of electron antineutrinos from nuclear reactors. The promise of experiments with reactor neutrinos is now exemplified by the rapid progress of the Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO) in China, which started data taking on 26 August last year (CERN Courier November/December 2025 p9).

Back to the standard paradigm

While the recent KATRIN and MicroBooNE analyses sought evidence for a hypothetical sterile neutrino beyond the standard scenario, JUNO operates within the standard three-flavour framework. Using just 59 days of data, the experiment independently exceeded the precision of previous global fits on two out of six of the parameters governing neutrino oscillations. These are the same mixing angle and mass splitting that govern the oscillations of solar electron neutrinos into other flavours – the very effect that GALLEX and SAGE were initially designed to study in the 1990s. As JUNO gathers data, it will resolve a fine-toothed comb that modulates this oscillation spectrum – the effect of a smaller mass splitting between the three neutrinos. JUNO is designed to resolve these tiny oscillations, revealing a fundamental aspect of nature’s design: the hierarchy of the small and large mass splittings.

“The JUNO result is very exciting,” says Huber, “not so much because of its immediate impact, but because it marks the very successful start of an experiment that will deeply change neutrino physics.”

The JUNO result is exciting because it marks the successful start of an experiment that will deeply change neutrino physics

JUNO is the first of a trio of a new generation of large-scale neutrino-oscillation experiments using controlled sources. Concluding a busy two-month period for neutrinos since the previous edition of CERN Courier was published, the launch of the nuSCOPE collaboration now dangles the promise of a valuable boost to the other two. One hundred physicists attended its kick-off workshop at CERN from 13 to 15 October 2025. The collaboration seeks to implement a concept first proposed 50 years ago by Bruno Pontecorvo: nuSCOPE will eliminate systematic uncertainties related to neutrino flux by measuring the energy and flavour of neutrinos as they are created as well as when they interact with a target.

If approved, nuSCOPE will study neutrino–nucleus interactions with a level of accuracy comparable to that in electron–nucleus scattering, and control the sources of uncertainty projected to be dominant in the DUNE experiment under construction in the US and at the Hyper-Kamiokande experiment under construction in Japan. DUNE and Hyper-Kamiokande both plan to study the oscillations of accelerator-produced beams of muon neutrinos. Their most specialised design goal is to observe another fundamental aspect of physics: whether the weak interaction treats neutrinos and antineutrinos symmetrically.

With three ambitious and sharply divergent experimental concepts, DUNE, Hyper-Kamiokande and JUNO promise substantial progress in neutrino physics in the coming decade. But KATRIN and MicroBooNE now leave precious little merit for the once compelling phenomenology of the single light sterile neutrino.

Two strikes, and you’re out.