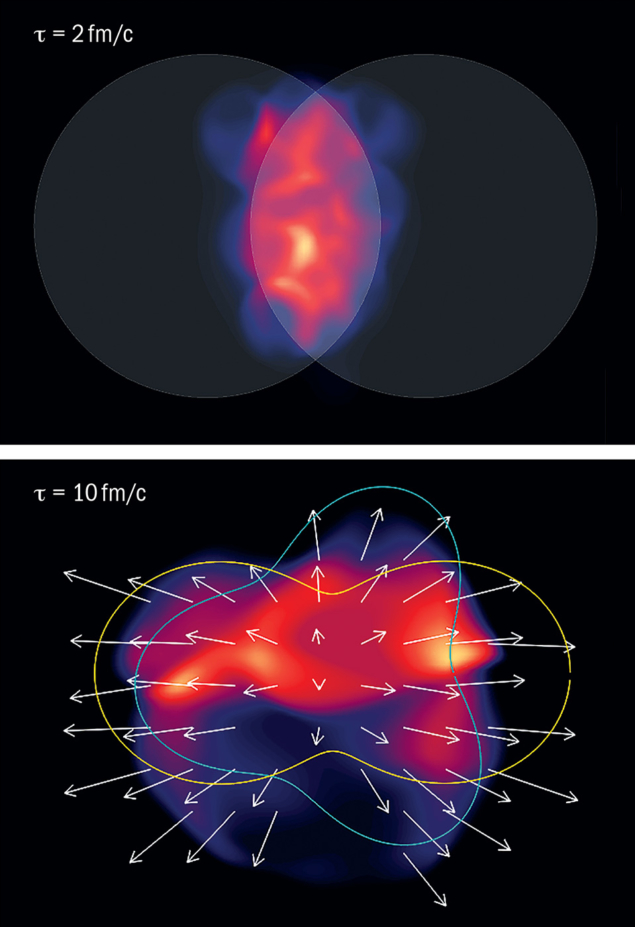

Microseconds after the Big Bang, quarks and gluons roamed freely. As the universe expanded, this quark–gluon plasma (QGP) cooled. When the temperature dropped to roughly a hundred thousand times that in the core of the Sun, hadrons formed. Today, this phase transition is reproduced in the heart of detectors at the LHC when lead ions careen into each other at high energy.

Heavy quarks are powerful probes of properties of the QGP

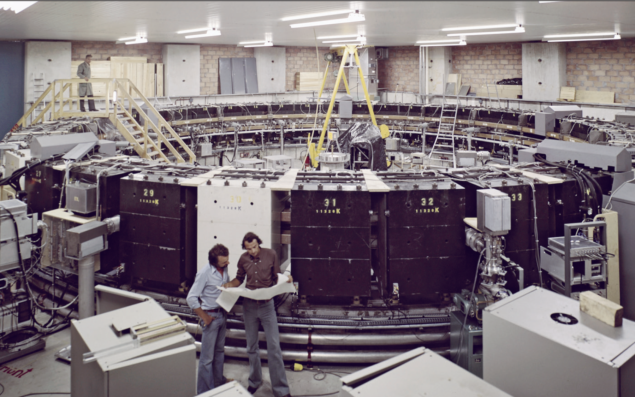

The experimental quest for the QGP started in the 1980s using fixed-target collisions at the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) and the Super Proton Synchrotron at CERN. This side of the millennium, collider experiments have provided a big jump in energy, first at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at BNL, and now at the LHC. Both facilities allow a thorough investigation of the QGP at different points on the still-mysterious phase diagram of quantum chromodynamics.

Among the most striking features of the QGP formed at the LHC is the development of “collective” phenomena, as spatial anisotropies are transformed by pressure gradients into momentum anisotropies. The ALICE experiment is designed to study the collective behaviour of the torrent of particles created in the hadronisation of QGP droplets. Following detailed studies of the “flow” of the abundant light hadrons that are produced, ALICE has recently demonstrated, alongside certain competitive measurements by CMS and ATLAS, the flow of heavy-flavour (HF) hadrons – particles that probe the entire lifetime of a droplet of QGP.

A perfect fluid

The QGP created in lead–ion collisions at the LHC is made up of thousands of quarks and gluons – far too many quantum fields to keep track of in a simulation. In the early 2000s, however, measurements at RHIC revealed that the QGP has a simplifying property: it is a near perfect fluid, with a very low viscosity, as indicated by observations of the highest collective flows allowable in viscous hydrodynamic simulations. More precisely, its shear viscosity-to-entropy ratio – the generalisation of the non-relativistic kinematic viscosity – appears to be only a little above the conjectured quantum limit of 1/4π derived using holographic gravity (AdS/CFT) duality. As the QGP is a near-perfect fluid, its expansion can be modelled using a few local quantities such as energy density, velocity and temperature.

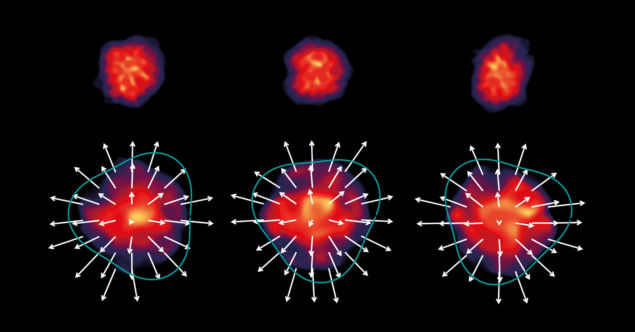

In noncentral heavy-ion collisions, the overlap region between the two incoming nuclei has an almond shape, which naturally imprints a spatial anisotropy to the initial state of the system: the QGP is less elongated along the symmetry plane that connects the centres of the colliding nuclei. As the system evolves, interactions push the QGP more strongly along the shorter symmetry-plane axis than along the longer one (see “Noncentral collision” figure). This is called elliptic flow.

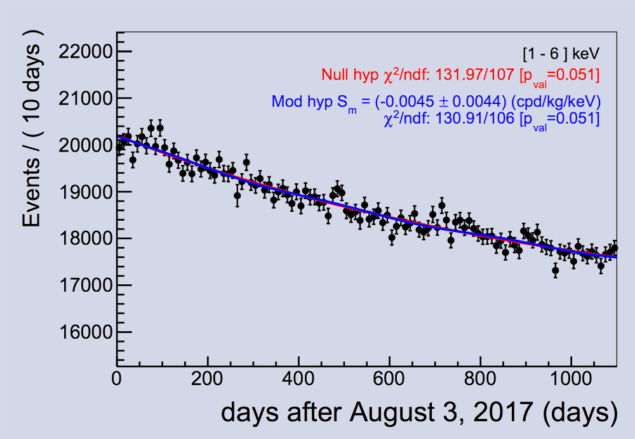

Density fluctuations in the initial state may also lead to other anisotropic flows in the velocity field of the QGP. Triangular flow, for example, pushes the system along three axes. In general, this collective motion is decomposed as 1 + 2 ∑ vn cos(n(ϕ–Ψn)), where vn are harmonic coefficients, ϕ is the azimuthal angle of the final-state particles in transverse-momentum (pT) space, and Ψn are the orientation of the symmetry planes. v1, which is expected to be negligible at mid-rapidity, is “directed flow” towards a single maximum, while v2 and v3 signal elliptic and triangular flows. The LHC’s impressive luminosity has allowed ALICE to measure significant values for the flow of light-flavour hadrons up to v9 (see “Light-flavour flow” figure).

The importance of being heavy

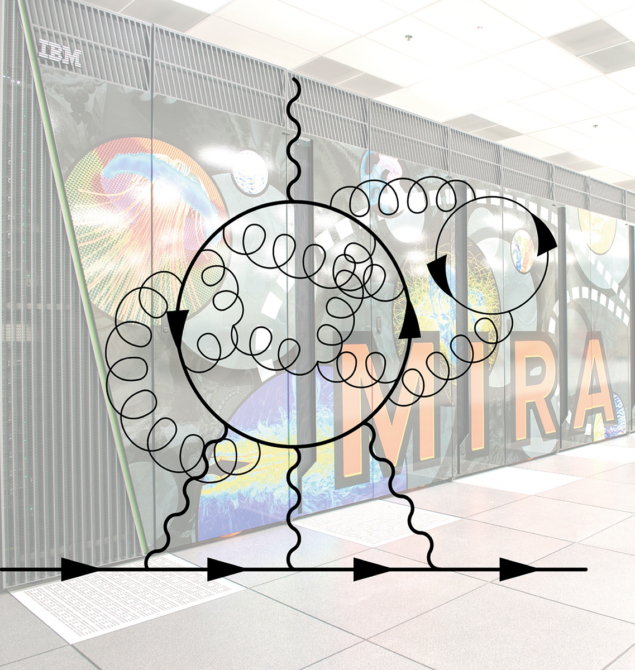

The bulk of the QGP is composed of thermally produced gluons and light quarks. By contrast, thermal HF production is negligible as the typical temperature of the system created in heavy-ion collisions is a few hundred MeV – significantly below the mass of a charm or beauty quark–antiquark pair. HF quarks are instead created in quark–antiquark pairs in early hard-scattering processes on shorter timescales than the QGP formation time, and experience the whole evolution of the system.

Heavy quarks are therefore powerful probes of properties of the QGP. As they traverse the medium, they interact with its constituents, gaining or losing energy depending on their momenta. High-momentum HF quarks lose energy via both elastic (collisional) and inelastic (gluon radiation) processes. Low-momentum HF quarks are swept along with the flow of the medium, partially thermalising with it via multiple interactions. The thermalisation time is inversely proportional to the particle’s mass, and so a higher degree of thermalisation is expected for charm than for beauty. Subsequent hadronisation brings additional complexity: as colour-charged quarks arrange themselves in colour-neutral hadrons, extra contributions to their flow arise from the influence of the surrounding medium when they coalesce with nearby light quarks.

In the past two years, the ALICE collaboration has measured the elliptic and triangular flow coefficients of HF hadrons with open and hidden charm and beauty. The results are currently unique in both scope and transverse-momentum coverage, and depend on the simultaneous reconstruction of thousands of particles in the ALICE detectors (see “ALICE in action” panel). In each case, these HF flows should be compared to the flow of the abundant light-particle species such as charged pions. Within the hydrodynamic description, particles originating from the thermally expanding medium at relatively low transverse momenta typically exhibit flow coefficients that increase with transverse momentum. Faster particles also interact with the medium, but might not reach thermal equilibrium. For these particles, an azimuthal anisotropy develops due to the shorter length of medium they traverse along the symmetry plane, but it is not as large, and anisotropy coefficients are expected to fall with increasing transverse momentum. When thermal equilibrium is achieved, it imprints the same velocity field to all particles: the result is a mass hierarchy wherein heavier particles exhibit lower flow coefficients for a given transverse momentum.

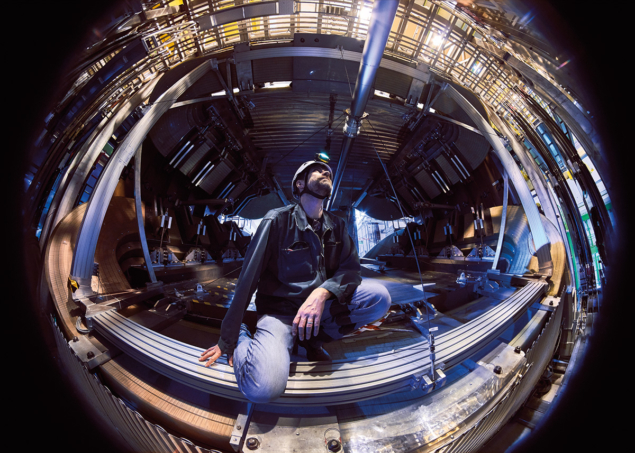

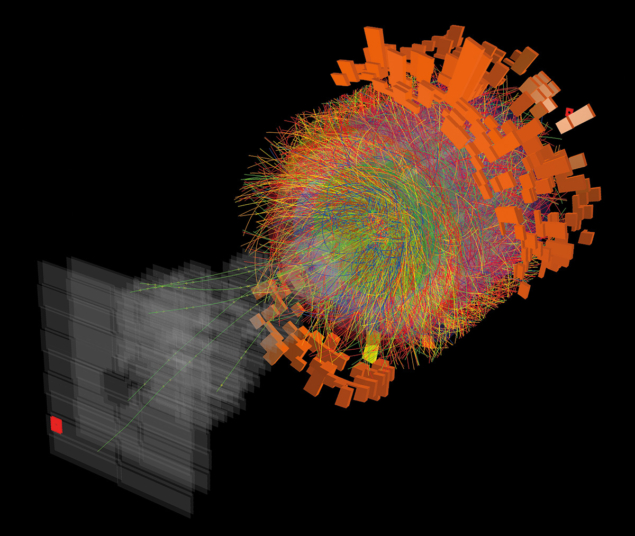

ALICE in action

The geometrical overlap between the two colliding nuclei varies from head-on collisions that produce a huge number of particles, sending several thousand hadrons flying to ALICE’s detectors (“0% centrality”, as a percentile of the hadronic cross section) to peripheral collisions where the two nuclei barely overlap (“100% centrality”). Since the initial geometry is not directly experimentally accessible, centrality is estimated using either the total particle multiplicity or the energy deposited in the detectors.

Among the cloud of particles are a handful of open and hidden heavy-flavour hadrons that are reconstructed from their decay products using tracking, particle-identification and decay-vertex reconstruction. Charm mesons are reconstructed through hadronic decay channels using the central barrel detectors. Open beauty hadrons are also reconstructed in the central barrel using their semileptonic decay to an electron as a proxy. Compelling evidence of heavy-quark energy loss in a deconfined strongly interacting matter is provided by the suppression of high-pT open heavy-flavour hadron yields in central nucleus–nucleus collisions relative to proton–proton collisions (after scaling by the average number of binary nucleon–nucleon collisions).

A small fraction of the initially created heavy-quark pairs will bind together to form charmonium (c–c) or bottomonium (b-b) states that are reconstructed in the forward muon spectrometer using their decay channel to two muons. Charmonium states were among the first proposed probes of the deconfinement of the QGP. The potential between the heavy quark and antiquark pair is partially screened by the high density of colour charges in the QGP, leading to a suppression of the production of charmonium states. Interestingly, however, ALICE observes less suppression of the J/ψ in lead–lead collisions than is seen at the lower collision energies of RHIC, despite the increased density of colour charges at higher collision energies. This effect may be understood as due to J/ψ regeneration as the copiously produced charm quarks and antiquarks recombine. By contrast, bottomonia are not expected to have a large regeneration contribution due to the larger mass and thus lower production cross section of the beauty quark.

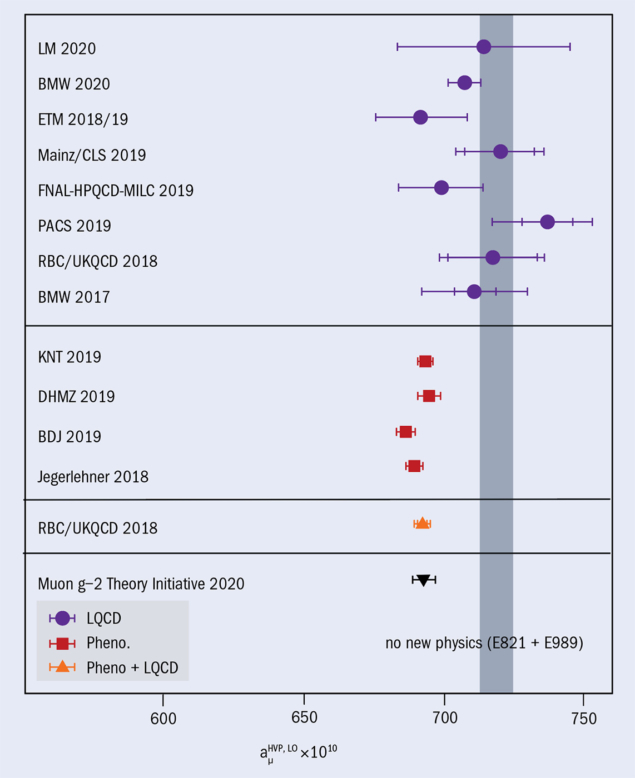

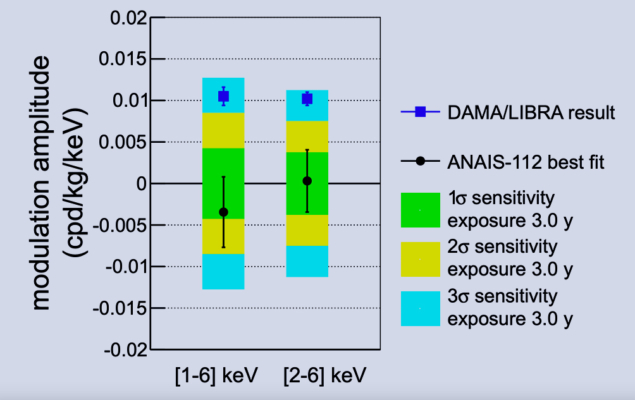

D mesons are the lightest and most abundant hadrons formed from a heavy quark, and are key to understanding the dynamics of charm quarks in the collision. A substantial anisotropy is observed for D mesons in non-central collisions (see “Elliptic flow” figure). As expected, the measured pT dependence is similar to that for light particles, suggesting that D mesons are strongly affected by the surrounding medium, participating in the collective motion of the QGP and reaching a high degree of thermalisation. J/ψ mesons, which do not contain light-flavour quarks, also exhibit significant positive elliptic flow with a similar pT shape. Open beauty hadrons, whose mass is dominated by the b quark, are also seen to flow, and in the low to intermediate pT region, below 4 GeV, an apparent mass hierarchy is seen: the lighter the particle, the greater the elliptic flow, as expected in a hydrodynamical description of QGP evolution. Above 6 GeV, the elliptic flows of the three particles converge, perhaps as a result of energy loss as energetic partons move through the QGP. In contrast to the other particles, ϒ mesons do not show any significant elliptic flow. This is not surprising as the transverse momentum of peak elliptic flow is expected to scale with the mass of the particle according to the hydrodynamic description of the evolution of the QGP – for ϒ mesons that should be beyond 10 GeV, where the uncertainties are currently large.

Theoretical descriptions of elliptic flow are also making progress. Models of HF flow need to include a realistic hydrodynamic expansion of the QGP, the interaction of the heavy quarks with the medium via collisional and radiative processes, and the hadronisation of heavy quarks via both fragmentation and coalescence. For example, the “TAMU” model describes the measurements of the D mesons and electrons from beauty-hadron decays reasonably well, but shows some tension with the measurement of J/ψ at intermediate and high transverse momenta, perhaps indicating that a mechanism related to parton energy loss is not included.

Triangular flow

Triangular flow is observed for D and J/ψ mesons in central collisions, demonstrating that energy-density fluctuations in the initial state have a measurable effect on the heavy quark sector (see “Triangular flow” figure). These measurements of a triangular flow of open- and hidden- charm mesons pose new challenges to models describing HF interactions in the QGP: models now need to account not only for the properties of the medium and the transport of the HF quarks through it, but also for fluctuations in the initial conditions of the heavy-ion collisions.

In the coming years, measurements of HF flow will continue to strongly constrain models of the QGP. It is now clear that charm quarks take part in the collective motion of the medium and partially thermalise. More data is needed to make firm conclusions about open and hidden beauty hadrons. All four LHC experiments will study how heavy quarks diffuse in a colour-deconfined and hydrodynamically expanding medium with the greater luminosities set to be delivered in LHC Run 3 and Run 4. Currently ongoing upgrades to ALICE will extend its unique advantages in track reconstruction at low momenta, and upgrades to LHCb will allow this asymmetric experiment to study non-central collisions in Run 3. In the next long shutdown of the LHC, upgrades to CMS and ATLAS will then extend their already impressive flow measurements to be competitive with ALICE in the crucial low transverse momentum domain, inching us closer to understanding both the early universe and the phase diagram of quantum chromodynamics.